3 Curriculum and the Purpose of Education

Ed Beck

Before We Read

Before reading, spend some time thinking about the different decisions that teachers make everyday as they plan their classes. The materials teachers choose, the way they organize a class, what is emphasized or not, and what choices are offered to the students all shape the student experience. To be an engaged teacher, it is important to build reflective practices and the habit of making informed and deliberate instructional choices. Think about your favorite experiences in school. What choices did the educators make that contributed to your experience?

Critical Questions for Consideration

As you read, consider these essential questions: What are the goals of education? How is the experience of the students impacted by what is written or missing into the curriculum? What hidden lessons are we teaching students? In what ways are we, as educators, shaping our schools and communities through our curricular and instructional choices?

Introduction to Curriculum

A simple definition of curriculum would be the subjects and the course of study in a school or college. Curriculum and instruction is an entire sub-field of education. Definitions of curriculum vary. The differences in the definition of curriculum from educator to educator provide clues to the varying stances on education and what it means to be educated. For example, curriculum may refer to knowledge students are expected to have or may refer to certain skills or competencies students should be able to demonstrate.

Some educators describe the curriculum as a prescription, a series of interactions, lessons, and topics that ought to be included in an education. This is the most traditional definition of curriculum. A prescriptive curriculum would define bodies of knowledge and ways that it would be taught to students, serving as a master plan for teachers and administrators. For this group of educators, the curriculum is a series of experiences mapped across the students’ journey of growth preparing them for their adult lives. The mandated and planned part of the curriculum is sometimes referred to as the explicit curriculum. The explicit or planned curriculum refers to the topics and standards covered by a class and perhaps the documents that align with the standards such as lesson plans, textbooks, and other teaching aids.

An alternative way to look at curriculum is from the students’ lived experiences. This more holistic view of curriculum would include the lessons taught to students both formally and informally. From the student viewpoint, there is more that is learned in school than the planned subject areas. The implicit or hidden curriculum refers to the lessons and values that are not explicitly taught, but are implied and inferred by the students from classroom and school culture. The hidden curriculum is taught to students often unconsciously through how instructors interact with students: types of behavior the teacher praises, rewards, admonishments, or classroom dynamics.

Explicit vs Hidden Curriculum

The hidden curriculum can have positive and negative effects on students’ learning and development. Social skills, norms, and community values may be positive aspects learned at school. Schools teach our children how to behave in class and is the primary socialization for young people. Positive aspects of this might include social norms for dress, how to speak with authority or persuasively, and how to think critically.

However, the hidden curriculum can also affect students’ academic performance and reinforce inequalities. The hidden curriculum can be the place where biases or prejudice are inadvertently passed on. The critical educator must constantly be evaluating their approaches to make sure that their practices align to their educational philosophy. The hidden curriculum is not easy to change, because it is unconscious, subtle, and pervasive. It can reinforce stereotypes and inequalities, and impact academic performance.

Paulo Freire and other critical theorists use the term critical consciousness to depict individuals’ deep understanding of the world, the ability to identify political and social inequities, and their dedication to taking action against those systems. As an educator, having a critical consciousness means regularly inspecting your own practices, the materials you choose, and the way you structure your classes. An Educator must consider what message and lesson they send students.

Imagine a newly certified Social Studies teacher teaching Global History. A Social Studies teacher is certified to teach all history from the beginning of time to the present day, plus other courses like economics, sociology, civics and government. While many civilizations are included in the curriculum as written by the state, this teacher notices the textbook is much more detailed about the Roman Empire than the Chinese dynasties. Remembering their own History and Social Studies instruction, the educator feels they are at a disadvantage as well, because their own teachers didn’t spend a lot of time covering the topics. While the new teacher has ideas and resources for how to add to a unit on Rome, they feel less prepared to teach about the cultures of Africa or Asia.

- While this story focuses on Social Studies, each certification area might have its own issues. What type of similar issues about content may come up in other classes?

- What message does it send to students if certain topics are given unequal time in the school year?

- Do you think that students know when a topic is their teachers favorite vs something the teacher feels they have to cover?

- What steps could you take to improve this situation?

What’s the hidden curriculum mean to you?

As an education student you have had the experience of being a student and very soon you will be visiting classrooms as an observer. The hidden curriculum has important implications for the socialization of students, but also potential for inequalities.

The hidden curriculum can have different aspects, such as cultural expectations, gender inequalities, racial biases, class and social privileges, and other aspects. Reflect on your experience in school, interactions with instructors and other school staff, and in classes.

Consider when hidden messages are embedded into the way content is communicated or taught. In mathematics education, a traditional way of thinking prioritizes the learning and following of the instructors rules and procedures for a type of problem. Students may be expected to solve all problems of a particular type in a routine way. Students who follow the procedure, but get the problem wrong may even receive more points than students who got the right answer but did it a different way. What message may this instructor inadvertently be teaching their students about creativity?

As you consider these questions, think both about your own experiences and your future classroom.

- How does the hidden curriculum impact students’ learning, attitude, and behavior?

- How does the hidden curriculum reinforce or challenge mainstream ideas and traditional power relationships?

- How can students and educators transform the hidden curriculum to promote more inclusive and equitable education?

The purpose of education

The purpose of education is a fundamental question that guides the design and implementation of educational programs. However, there is no single answer to the question of what the purpose of education is and what curriculum should be. In this chapter, we will explore three major categories of curriculum that reflect different emphases on the purpose of curriculum: the learner-centered curriculum, the society-centered curriculum, and the knowledge-centered curriculum.

As you read these next sections, think about your definition of education. While it is practical to categorize educational approaches, remember that these emphases are not mutually exclusive or incompatible. In practice, educators adopt a combination or balance of approaches.

Learner Centered Curriculum

The central premise of the learner-centered curriculum entails designing instruction for the student’s needs, interests, and abilities. By fostering student engagement, teachers hope to encourage more autonomy in students’ own learning, developing their student’s talents and potential.

Practitioners of the learner-centered curriculum work hard to individualize instruction, differentiate it to each student, allowing students to have choices in their learning. The learner centered curriculum values the diversity and uniqueness of each student and seeks to create a supportive and respectful learning environment.

One of the guiding principles of learner centered curriculum is the doctrine of interest. The doctrine of interest is the idea that students should study what they want to study. In this mindset, the curriculum is built based on the individual student’s interest. Proponents of the doctrine of interest argue that forcing a student to learn what they aren’t interested in is largely a waste of time. Critics contend that to truly embrace the doctrine of interest, the teacher must trust that the students have the ability to choose wisely what will benefit them the most in the future.

The role of the instructor in the learner centered classroom has multiple responsibilities. They must ensure a learning environment that anticipates students’ needs, interests, and appropriately challenges their abilities. While providing autonomy in the learning process, the instructor needs to encourage active participation, promote collaboration, and suggest activities that balance the learners’ interests.

Explore more:

Many educational psychologists and philosophers have contributed to the framework of the learner centered curriculum. Explore some of the educators that have contributed to this framework.

John Dewey

John Dewey was a major educational reformer and college professor in the early 1900s. He advocated for a progressive educational system. Dewey advocated for education to be a social and collaborative endeavor, with hands on and real-life applications.

Additional Resources on Dewey

John Dewey: Portrait of a Progressive Thinker | The National Endowment for the Humanities (neh.gov)

Maria Montessori

Maria Montessori was an Italian physician and educator. She advocated for a method of education prioritized respecting the individuality of children, independence, and stimulating curiosity.

Additional Resources on Montessori

Maria Montessori – Quotes, Theories & Facts (biography.com)

Montessori Education

Learner-Centered Curriculum in Practice

Montessori education is an example of a learner-centered curriculum. It is based on the idea that children are eager to learn. Students at Montessori schools can initiate and direct their own learning in a prepared environment that offers materials and activities based on a variety of interests. In Montessori education, the prepared environment refers to a learning space with educational activities at the ready which can be chosen and utilized by the students.

Montessori education emphasizes hands-on learning and real-world skills, and allows children to work at their own pace on activities they choose. Montessori education fosters independence, responsibility, and self-discipline, as well as cooperation, collaboration and social skills.

Walking into a Montessori classroom, a guest would not see a teacher in the front of the classroom or children of all the same age. Instead, children would be grouped in similar age ranges, typically 2-3 years apart, and there would be several teachers in the room, who are called guides. Students choose their own hands-on learning activities around the five main topics of Montessori education: Practical Life, Math, Language, Sensorial, and Cultural. Students have long work periods of 2-3 hours where they can work through activity-based lessons, or they have the freedom to move between several activities.

Montessori education prioritizes hands-on manipulatives to aid student learning through experiences. A well-designed Montessori activity integrates hands-on learning, includes multiple domains of knowledge and integrates them in a holistic way. A student who is interested in the solar system might pick for themselves materials off a shelf. There would be physical manipulatives for them to interact with, such as wood blocks that symbolize the planets, or cards with facts and information about each planet. Students would have tasks to do, such as classifying planets in different ways or placing them in order. The instructor would observe the student, try to identify if and when to intervene, and may attempt to give the student a new prompt or challenge to work through with the materials they have chosen.

Critics of Montessori education point to the large cost of running these schools. With one adult per every twelve children, Montessori schools are often private schools with long waiting lists and expensive tuition.

Project Based Learning

Learner Centered Curriculum in Practice

Project Based Learning (PBL) is a method of teaching where students investigate or respond to an authentic problem or question over an extended period of time. Not simply tacking on a project at the end of a unit, practitioners of Project Based Learning carefully design a project so that through completion of the project students engage with the important knowledge and skills that students need to learn.

A key part of courses that utilize project-based learning is that students work on an authentic or real-world problem. Students may then collaborate to develop what information they need to know and want to know to address the question. This may include working with experts and community members, research, and collaboration. The teacher would help the students create a project plan on how they will collaborate and how they will present their work.

An instructor using a project-based approach would be responsible for working with groups of students. While the students would be expected to come up with the questions, finding resources, and applying that information to their project, the instructor would be intervening when necessary, suggesting additional framing questions, aiding students to find resources, and making sure groups are working well together.

Many proponents of project-based learning believe that the public product or presentation is a key factor in the success of project-based learning. The public sharing of projects reinforces the idea that the students are working on real world problems and that their work is intended for an audience greater than just their own teacher or class.

Project Based Learning can be integrated into a single course or may be used as an opportunity to collaborate between multiple subject areas. Proponents of PBL argue that it encourages students to deal with complex and ill-structured problems, integrate information from multiple sources, and have ownership over their learning. Critics say that PBL takes significant resources and time and that it may lead to missed content or gaps in knowledge due to the time projects require.

Society Centered Curriculum

The society-centered curriculum is based on the idea that education should be designed around society concerns and community issues. In this approach to education, the purpose of education is centered around future needs of the community. This approach focuses to prepare students for their roles and responsibilities as citizens and also to address the problems and challenges that society faces.

The society-centered curriculum shares many aspects with the learner-centered curriculum. Both could be classified as part of the progressive educational movement, a reaction to earlier knowledge-centered approaches that prioritized education according to classical disciplines and traditional subjects. Both learner-centered approaches and society-centered approaches seek to focus education on the whole person, making it more democratic, and empowering students.

While the learner-centered curriculum emphasizes the individual agency of students, the society centered curriculum emphasizes collective well-being and the needs of the community. The society centered curriculum targets societal issues and trends. Practitioners that favor a society centered approach may state among their goals preparing students to be engaged citizens and prepared to interact with their government, may focus on leadership, advocacy and teamwork as key part of their classroom, or may emphasize subjects and topics where they see a need or shortage of workers.

Explore More:

Many educational psychologists and philosophers have contributed to the framework of the society centered curriculum. Explore some of the educators that have contributed to this framework.

Paulo Freire

Paulo Freire was a Brazilian educator and a leading scholar of critical pedagogy. His book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, was published in 1968, and outlined a new relationship between teachers and students with students acting as co-creators of knowledge. Freire believed that education and critical thinking were the essential foundation to democratic societies.

bell hooks

bell hooks was an educator and social critic. She is best known for applying critical theory to the American education system. As a black feminist and educator, hooks wrote about the influences of race, capitalism, and gender on the educational system. Her 1994 book, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom, reflected on her time in segregated black schools and her time at integrated schools. hooks describes her time in all black schools as joyful and her time at integrated schools as traumatic, challenging educators to understand how the school culture could be oppressive for students.

bell hooks was born Gloria Jean Watkins. She took on the name bell hooks, which was her great-grandmother’s. She chooses not to capitalize her name to focus on the message, not the person.

Freire’s Brazil

Society-Centered Curriculum for Societal Change

Freire’s philosophy on education was a direct reaction to the historical context of Brazil in the 1970s. At this time, Brazil was a third world country in the original meaning of the term, meaning that they were not directly aligned with either the United States or the Soviet Union during the Cold War. From 1964 to 1985, Brazil was under a military dictatorship that saw gradual democratization, eventually leading to a new democratic constitution and government in 1988.

Working as an educator during those times of change, Freire saw education as a means to overcome all types of oppression: political, economic, and intellectual. The goal of his pedagogies were the intellectual liberation of both the oppressed from the colonialist and capitalist social structures. He hoped education would change the people’s mentalities and processes so that a truly democratic society could emerge. Freire warned that an uneducated society would be susceptible to misinformation, and that democracy would be fragile if the population made decisions based on emotional thinking rather than critical thinking.

To Freire, education should empower the people to:

- Discuss the real problems of their time and come up with solutions.

- To empower students to reevaluate constantly using scientific and systematic methods.

- To view themselves as part of and in conversation with their society.

- To assume a critical attitude towards the world and in doing so be prepared to change it.

To underscore the differences between his model of education, which sees students as partners in the classroom and emphasizes the knowledge each student brings to the table, Freire derisively used the phrase “the banking model of education” to describe past practices. In the banking model of education, students are treated as empty vessels, needing to be filled with information. Freire believed this mindset reinforced racist colonial attitudes. In The Pedagogy of the Oppressed, he wrote about an alternative, which was to respect student knowledge, to include their voice in the curriculum, and to empower them. Freire’s pedagogy is a criticism and reaction to colonialism where only the dominant culture’s ideas, literature, and ways of understanding are valued. Critical pedagogies roots are, then, an act of decolonial resistance to colonialism and oppression

STEM and P-TECH in New York

Society Centered Curriculum for Workforce Training and Modernization

Another way to think about society centered curriculum is to forecast future needs of the community and to promote additional emphasis to those topics throughout the curriculum. Integration of STEM throughout the curriculum is not a new push. In 1957, as a result of the Soviet Union launching the world’s first artificial satellite, the United States education system promoted Science and Mathematics education as an urgent need for national security because of fears of Soviet scientific superiority.

Today, the emphasis on technology, high tech manufacturing, and coding skills can be attributed to a few factors: the high paying coding and computer engineering positions, a recognition that all careers are being influenced by changing technology, and a desire to own the supply chain for high tech products such as computer chips. In 2022, Congress passed the CHIPS and Science Act, an incentive program to bring chip manufacturing to the United States. One of the beneficiaries of the CHIPs act is Upstate New York where the company Micron has promised to build a semiconductor fabrication facility.

Even before Micron’s announcement, New York State had an established P-TECH program (Pathways in Technology Early College High School). The structure of P-TECH programs varies, however many are accelerated high school and Associate degree programs where students can earn a degree in a high demand field such as advanced manufacturing or cyber security. After Micron’s announcement to build one of the largest fabrication facilities in the United States, New York State announced an additional $31.5 Million to create advanced manufacturing classrooms and create partnerships between K-12 Districts, Community Colleges, and the state’s Technical Colleges.

P-TECH programs try to put students in authentic challenges in a very career focused way. Students may be collaborating with industry professionals, researching current issues, and applying problem solving to real situations. Students in these programs still have to fulfill the same general education requirements as their peers but may adapt the curriculum to focus more on the critical thinking, teamwork, and communication skills needed in their chosen sector.

Advocates of P-Tech and STEM education programs highlight the potential for students to walk into high growth and high demand jobs and satisfy a current crisis where technical and advanced manufacturing jobs may go unfilled because there aren’t enough qualified applicants. Critics may worry that students are specializing in careers too early and that if other areas of education are neglected, that graduates of programs like the P-TECH programs might not have the broad education needed to switch careers later in life or be missing out on the broad exposure to a wide variety of topics.

Knowledge Centered Curriculum

The goal of the knowledge centered curriculum is to teach all students a broad range of subjects that are considered essential. In a knowledge centered approach, there is a canon of agreed upon essential knowledge or skills that are scaffolded across the educational experience. Traditionally, students are taught a variety of disciplines separately including science, mathematics, the humanities, and art.

The knowledge centered approach is deeply rooted in traditional educational philosophies. The focus is on skills and facts from academic subjects. Although there may be some interdisciplinary work, the majority of the time is spent working with teachers who are themselves specialists in one area or another. Proponents of the knowledge-centered curriculum believe that a foundation in math, science, literature, and history is the best preparation for life because the broad skill set will allow the educated person to adapt to multiple environments. While the academic curriculum isn’t opposed to career training, proponents of the knowledge-centered curriculum prefer that specific career training comes after high school, and students are not identified and tracked into groups who will go to college and those who will go directly into the workforce. This is because the advocates for the knowledge-centered curriculum believe that broad exposure to academic disciplines is the goal. The argument is that a well-educated and well-rounded person is adaptable and prepared for the future.

Textbooks as curriculum

One example of the knowledge-centered curriculum is the textbook. Modern textbooks consist of a multitude of learning materials, multimedia, question banks, supplementary resources, and teachers guides. A giant industry, three or four leading companies produce the majority of textbooks in the United States. Many of the curricular battles play out in what is included in the textbook. There has been a drive to make sure more diverse voices are present in all textbooks, to try to make sure students are exposed to a wide variety of cultures. This push for inclusion has also prompted a backlash from parent groups and lawmakers who feel that a progressive agenda is being pushed on students.

While there are legitimate fears of over standardization and teachers being forced to use scripted or canned curriculum, textbooks have been an ubiquitous part of most American schools. Textbooks have strengths. They are organized and supply a structure and sequence for complex subject matters. Teacher certifications can be very broad, and instructors can find themselves teaching several subjects and will likely not have the time to assemble resources of the appropriate difficulty and scope for their students.

Critical teachers must be aware of the strengths and limitations of textbooks. Part of building a critical consciousness is being aware that textbooks may contain biased coverage of certain topics, may not have problem-solving or higher-level activities for students, and may limit students’ exposure to a wide variety of resources because the textbook becomes the single source of information. Expert teachers make informed choices with their text, including when to use it, when to supplement with outside resources, and how to structure class with or without it.

Explore More:

Many Educational Psychologists and Philosophers have contributed to the framework of the Knowledge-Centered Curriculum. Explore some of the educators that have contributed to this framework.

E.D. Hirsch Jr.

Essentialism

E.D. Hirsch Jr. was a professor of English at the University of Virginia. Hirsch put forward the idea that knowledge, not competencies or skills, should be the goal of curriculum. Hirsch’s Core Knowledge Curriculum lays out what he considered to be essential for Americans to possess in common. His 2020 book How to Educate a Citizen is a follow up to his 1987 book Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know.

Mortimer Adler

Perennialism

Mortimer Adler is author of the Paideia Proposal (1982) in which he laid out the need for a classical education focused on the perennial or everlasting ideas from the greatest thinkers and philosophers. Adler’s approach calls for everyone to study the great thinkers like Plato, Aristotle, and Thomas Aquinas.

The Committee of Ten

Standardization of the American High Schools

In 1892, a group of American educators were brought together to make recommendations on the future of high school education. Drawing heavily from colleges and universities, and led by the president of Harvard University, the Committee of Ten made recommendations to standardize the high school curriculum. The central part of the recommendation was to create a core curriculum that would prepare students for higher education and the workforce.

The committee’s recommendations centered on a core curriculum comprising of literature, classical languages, mathematics, science, and history. The recommendations of the committee of ten create a structure for high school that still might feel familiar to students. English, history, math and science. Math should be taught in a sequence of algebra, geometry, and trigonometry. Science should be taught every year with a year each on practical geography, biology, chemistry, and physics in that order. A major difference between the curriculum of the early 1900s and today would be the early curriculum’s emphasis on classical languages such as Greek and Latin. A high schooler would have taken both Greek and Latin, as well as two modern languages, usually French and German.

The Committee of Ten’s work laid the foundation for the structuring of high school in the United States, setting the precedent for core subjects. While there has been extensive reforms to education over the years, the initial structure recommended by the Committee of Ten is still visible.

The legacy of the committee lives on in a few different ways. The high school schedule still bears a close resemblance to the committee’s recommendations, but perhaps the more important and enduring legacy is the idea that every student should take this college preparatory curriculum. An ongoing debate since the release of the Committee of Ten’s initial report has been the need to balance between standardized curriculums and the need for flexibility and student-centered approaches in modern education.

Advanced Placement (AP) Tests

Each year, more than a million students challenge demanding Advanced Placement tests in high school hoping to gain college credit for taking an advanced high school course. Run by the organization The College Board, the same organization that runs the SATs, Advanced Placement tests have become a benchmark by which students and schools are judged. These high stakes exams are marketed towards high schoolers and their parents as a way to show rigor in their high school education and a way to stand out in the college admission process.

To be able to teach an AP Course at a high school, the school must apply to the College Board, submit a detailed curriculum outlining alignment to the AP test, and must choose a textbook that has been approved by the College Board. AP Courses are available in math, science, history, english, world languages, and a newer capstone program in research methodology.

Students in AP Courses are challenged with a broad curriculum that includes all the topics typically taught in a college introductory course. Critics of the AP Exams have said that AP courses focus too much on a wide breadth of materials, but lack the time to do a deep and thorough analysis of individual topics.

The number of AP courses taught and how the students score on them feature prominently in how American high schools are compared to each other in ratings such as the US News ratings of High Schools. School administrators attach letters in their student college applications stating how many advanced courses are available at their institutions. 35% of high school students who graduated in 2022 took at least 1 AP course, and college credit for high school courses has continued to grow as a trend and expectation in the American High School experience.

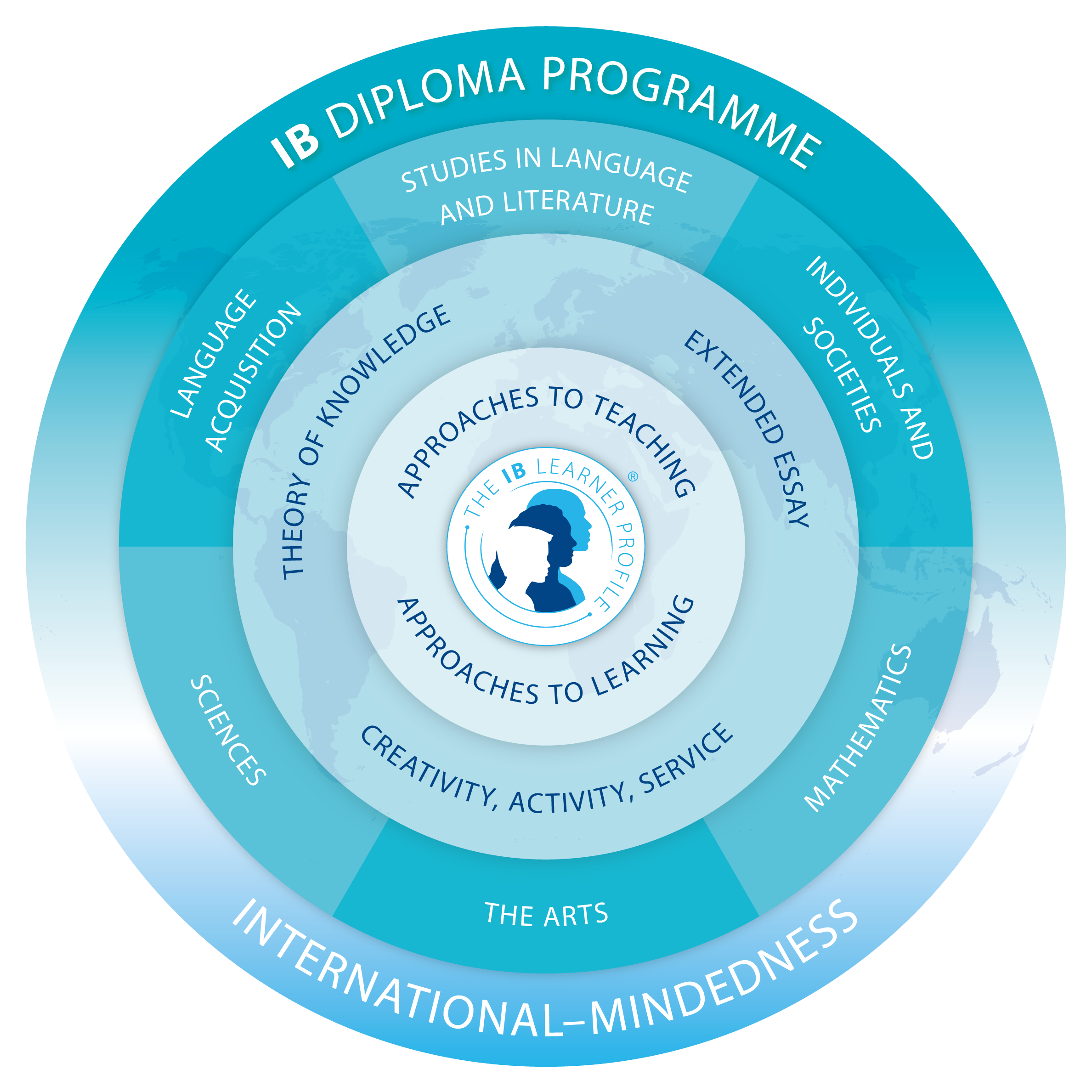

The International Baccalaureate (IB) Diploma Program

The International Baccalaureate Organization is a non-profit educational organization based out of Switzerland. Since the 1960s, the IB Diploma program has been utilized in international schools catered to the families of multinational corporations, military families and mobile groups. In the United States, IB diploma programs are often used as an accelerated learning opportunity for exceptional students.

The IB Program consists of coursework in 6 main areas: Language, Second Language, Individuals and Societies, Mathematics or Computer Science, Experimental Sciences, and The Arts. In addition to the coursework, all students take a required Theory of Knowledge Course, have to do experiential learning through their Creativity Action Service requirement, and do an independent research project or extended essay of 4,000 words.

The purpose of the IB diploma is to have an internationally recognized qualification that could be recognized all over the world, to have an international intellectual framework, to educate the whole person, and to develop inquiry and thinking skills. The IB diploma is recognized and well regarded, with similar prestige for graduates as those who score highly on Advanced Placement or AP tests through the College Board. A major difference between the IB programs and Advanced Placement programs is that the AP Tests are single high stakes tests, while in the IB program testing is integrated throughout the school year, with external graders used to rate students and the schools.

For a high school to participate in the IB Diploma program, administrators and teachers must be certified by the IB Organization, attend additional professional development, and continual education.

Advocates for the use of IB program and its high standards praise the international focus, rigor, and emphasis on critical thinking and research. Critics bring concerns about the demanding nature of the IB curriculum and stress on students.

Teacher Agency in Curriculum

In education, the concept of curriculum is an important thing for the future teacher to consider. Educators must constantly be examining and reflecting on their curricular goals and analyzing their teaching tools and methods to make sure that all parts of the students’ experience, both the explicit plans and the hidden lessons conveyed match their purpose of education.

Remember the warning as we introduced the learner centered, society-centered, and knowledge-centered classification. While classification systems are convenient, the truth is that most educators will incorporate a spectrum of approaches, and the examples given in the chapter may represent the extreme implementation of these philosophies. The main takeaways may be the ideals that each approach embodies from individual empowerment and societal reconstruction to comprehensive knowledge and exchange. There are ways to give learners voice and control in their education that are not Montessori education or implementing full Project Based Learning.

Analyzing the American education system, at first glance it has many of the criteria of a knowledge centered curriculum, with an articulated curriculum of facts, competencies, and skills that students should be able to demonstrate their mastery of in defined subject areas. However, there is space in this curriculum for instructors to use their discretion and expertise.

As educators, it is those instructional choices that wield substantial power in shaping the student experience and our schools. It is essential to build a critical consciousness, continually evaluating practices and questioning the impact of those choices. By embracing this agency, educators can blend curricular and instructional philosophies and find their personal approach to meeting diverse student needs, to giving students voice and choice in the curriculum, and making sure that today’s students are tomorrow’s citizens and neighbors.

Being able to articulate one’s purpose of education is an important first step in the process of becoming a critical educator. Once your goals are well defined, the next step is the critical awareness to make sure that the instructional methods and content match the stated purpose. As agents of change, educators have the opportunity to influence and shape curricular choices that shape our students, schools, and societies.

Activity: Your Philosophy of Education

What is your teaching philosophy? What do you feel your role should be as a teacher in our educational system? Teacher candidates are often asked to explain their philosophy of education as part of the application and interview process.

Your teaching philosophy should be 2-3 pages in length and written in first person and in present tense. You will want to include examples and descriptions so your reader can “see” you in your classroom—these may be specific teaching strategies you use, assignments you integrate, discussions you have with students, or the physical environment you create.

Some questions to get you started:

- Begin by making a list of what you feel education should do—what is the purpose of education or what are the goals of education? Are there specific educational theories that you believe in strongly?

- Make another list of teaching methods you feel best help you to reach this purpose. How do you interact with students? What does your classroom look and feel like? What kind of assignments do you believe are best? How do you support your students? How do you assess learning has taken place? What kind of strategies do you use to teach your specific discipline?

- Jot down two to three specific examples of your teaching methods and describe how you apply these in the classroom. What does this specifically look like?

- Also, write a justification of how you feel that your particular teaching methods help your students to reach your chosen goals of education. Why do you feel these are the best strategies for reaching the ideal education?

Once you have these portions written, go through these and select the teaching methods and the examples of these that you feel most fully convey your style of teaching.

Activity Adapted from Writing a Philosophy of Education by the University of Arizona Global Campus Writing Center shared with a Creative Commons Attribution License.

Glossary

Curriculum: The subjects, knowledge areas, and skills that students are expected to learn. The course of study.

Critical Consciousness: the ability to recognize and analyze systems of inequality and the commitment to take action against these systems

Doctrine of Interest: The belief that student interests should be the deciding factor about what to study.

Explicit Curriculum: The planned part of the curriculum which includes the topics, standards, and learning materials used in a course of study. The word explicit is used to differentiate and contrast it from the hidden curriculum.

Hidden Curriculum: The lessons that arise from the culture of the school and the behaviors, attitudes, and expectations that characterize that culture

Ill-structured problem: A real-world problem that may not have a clean or simple solution. Illstructured problems require students to do research and creative thinking

Knowledge-Centered Curriculum: An approach to curricular design that is subjectbased and aims to teach students disciplinary knowledge.

Learner-Centered Curriculum: An approach to curricular design where students interests determine the direction and design of the educational experience. Educators customize learning paths for individual students.

P-TECH Program: A high school to community college pathway program meant to encourage students to prepare for high-paying tech manufacturing jobs.

Prepared Environment: In Montessori Education, the prepared environment is a classroom with materials and manipulatives that the students can see, select, reach themselves, and begin to explore.

Progressive Educational Movement: A movement in educational history that rejected rote learning and recall in favor of experiential learning and authentic tasks.

Project Based Learning (PBL): An approach to education where students learn by completing projects that are designed to mimic real-world situations.

Society-Centered Curriculum: An approach to curricular design where the needs of the society are prioritized. Lessons and subjects are organized based on community needs or problems.

Figures

Maria Montessori and John Dewey by Natalie Frank is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

bell hooks and Paulo Freire by Natalie Frank is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Mortimer Adler and E.D. Hirsch Jr. by Natalie Frank is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License