1 The Cultural Narratives of Teachers

Thor Gibbins and Elyssa Stoddard

Before We Read

Before reading, spend some time thinking and writing on some metaphors about teachers, teaching, and students that you have overheard or may have used, e.g., “teachers are gardeners” or “teachers are sculptors.” What are the implications of these metaphors on what teaching means and what agency do students have in these metaphors? Have you seen any movies or television shows about teaching and teachers that you can point to as examples of these metaphors? Explain possible reasons writers, media producers, and distributors might benefit from creating these narratives about teaching, teachers, and students.

Critical Question For Consideration

As you read, consider these essential questions: How has the media framed teachers in the United States to construct cultural narratives and beliefs about teachers and the teaching of youth? And how have these narratives shaped how we, as educators, see ourselves as teachers and our students in our current or future classrooms?

How Media Constructs Cultural Narratives

Whatever our reasons for becoming an educator, it has been molded and shaped by cultural narratives of teaching and teachers. These narratives spring from the spectacles emerging from popular culture’s attempts at making sense of the events of social change. Film, television, and literature create spectacles for us to consume and internalize. Literary theorist and philosopher Roland Barthes (1957) likened the spectacle of professional wrestling as a cultural metaphor for how his society made sense of the changing times in post-World War II France. Barthes, in his analysis of popular culture and professional wrestling, outlined a method of scholarship that can trace narratives created by these cultural spectacles to the underlying ideologies enveloping a particular society. The purpose of this chapter utilizes Barthes’ critical analyses to trace narratives about teaching and teachers within the advent of modern film and television. In doing our critical analyses, we connect these narratives to landmark events that influenced public education throughout most of the last century as well as the first part of this one.

MEET A SCHOLAR

Roland Barthes (1915-1980) was a French philosopher who wrote seminal works in the fields of literary criticism and semiotics. Barthes was an influential writer within structuralist and post-structuralist literary theories. Structuralism asserts that our experience of the world entails a visible level of surface phenomena and an invisible level (Tyson, 2015). The invisible level contains structures and systems of meaning that help us make sense of our world. Barthes proposed there are underlying structures which produce meaning. “Texts” emerge from these structures which allow spectators, viewers, readers, etc to experience catharsis, or emotional release, whenever they experience reading a book, watching a movie, or watching a sporting event. For theorists like Barthes, the world can be read as a text and it is the underlying cultural structures that shape our interpretation of the world.

Critical Discussion Activities:

- Teen and coming-of-age movies have been popular cultural texts since James Dean starred in Rebel Without a Cause (1955). Select a popular teen movie from your generation and outline the character tropes within the movie. How does this movie portray youth? Do these caricatures connect to other social narratives about teens and youth cultures?

- Choose a cultural artifact, e.g., commercial, television show, music video, etc, that targets teens and young adults. What type of assumptions do these media make about teens and youth cultures? For example, do they infanticize teens and/or do they create positive or negative stereotypes of youth? What are the implications of these narratives on social perceptions of youth?

While most narratives of teaching and teachers in the United States may not spring forth from the top ropes of professional wrestling programs like World Wrestling Entertainment (WWE), popular film and television can create spectacles that shape our cultural understandings of teaching and teachers. For example, action movies create stories that clearly outline who are the “good guys” and who are “bad.” As children , we take the narratives of popular culture and enact them as we play. As we continue consuming these same stories, we begin to internalize these stories, which frame how we see the world. The frame is hidden as we perceive the world much like a lens of a camera that can focus on specific details while blurring out either the background or foreground. Media in its various forms, e.g., literature, film, and television often frames teachers and youth in ways that create stereotypes for us to internalize and shape our perceptions of teachers and youth. These mediated caricatures surrounding education lead, then, to archetypes of teachers and youth that may become problematic. In a sense, these archetypes may reinforce ideas about teachers and young people that may hinder the goals of a high quality education for all members of our country.

Like the “good guy,” the “bad guy,” and other tropes found in action movies, the spectacle of storytelling surrounding educational narratives creates easily castable roles for teachers: the wise sage/saint, the white savior/martyr, the outsider/disruptor, the loveable buffoon, and the villain. We, as educators, have all internalized these tropes at times and may have even performed the scripts in these teacher stories early on in our careers as educators. Our purpose of unveiling the spectacle of education is to critique the underlying sociological purposes of maintaining these caricatures of teaching that do not have any real connection to the lived experiences of teachers and students.

| Teacher Trope | Example(s) |

|---|---|

| Wise Sage/Saint | Boy Meets World, Harry Potter, Mr. Holland’s Opus, |

| Loveable Buffoon | School of Rock, 10 Things I Hate About You, Mr. Vargas in Fast Times at Ridgemont High |

| Outsider/Disruptor | Kindergarten Cop, Sister Act, School of Rock |

| White Savior or Martyr | Dangerous Minds, Freedom Writers, |

| Villain | The Breakfast Club, Ferris Buehler’s Day Off, Bad Teacher, Mr. Hand in Fast Times at Ridgemont High |

In this chapter, we apply critical examinations of how popular media frames these narratives. Moreover, we outline other more problematic narratives of education and how these narratives can be used by those in power to create systems of oppression and social replication. These cultural narratives tend to lie beneath the surface of the explicit goals educational stakeholders and politicians state in the public record. Thus, we will attempt to reveal these latent, or hidden, narratives that help create a hidden curriculum (Anyon, 1980). Chapter two will go into more detail about the import and consequences of a hidden curriculum. However, in order to reveal the hidden curriculum and its effects on education, this chapter takes a closer look at the cultural narratives constructed by the media that underlies popular culture: literature, film, and television. This chapter examines cultural narratives that maintain hegemony, or oppression,; challenge hegemony; and subvert, or transgress, hegemony related to teachers and youth in the United States.

Throughout this chapter, we encourage all educators (pre-service education students, teacher educators, educational leaders) to critically evaluate our own biases and prejudgments about public education and the role of teachers in either maintaining hegemonic narratives or challenging or perhaps subverting them.

Popular Culture Goes to School: The Shifting Cultural Narratives of Public Education, Teachers, and Students in Film and Television

Teachers in Films Set in 1930-1950s

Teachers and schools were not the primary protagonists or setting in the early years of cinema. However, Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939) is one of the earliest films depicting a teacher as its primary protagonist. The primary theme for the film dealt with a teacher’s dedication to teaching and the lives of his students. While set in England, Goodbye, Mr. Chips (1939) introduces the teacher/saint (Table 1.1) about teaching and teachers that can be easily traced to more contemporary movies like Dead Poets Society (1989) and Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone (2001). In the film, a wise retired teacher Mr. Chipping, or Mr. Chips, reminisces about his life spent as a teacher at a private boarding school for boys. Mr. Chips has dedicated his life as a teacher. The film highlights his transformation from a bumbling beginning educator to a wise veteran teacher who inspires the best in the young men he leads at this school where he also resides much like priests’ devotion to the church and their congregation. In a sense, Goodbye, Mr. Chips equates becoming a teacher to joining the priesthood. While there is a love interest and a short segway into Mr. Chips’ life away from teaching, the film instills an unspoken creed for teachers that one must adhere and devote one’s whole self to teaching at the expense of one’s other interests and social life to the point of taking a de facto vow of celibacy. It may appear as hyperbole at first glance, however, the rules for teachers from 1872 (Webster Museum, 2023) seem to outline the teacher as saint archetype that Mr. Chips embodies:

- Teachers each day will fill lamps, clean chimneys

- Each teacher will bring a bucket of water and a scuttle of coal for the day’s session

- Make your pens carefully. You may whittle nibs to the individual taste of the pupils.

- Men teachers may take one evening each week for courting purposes, or two evenings a week if they go to church regularly.

- After ten hours in school, the teachers may spend the remaining time reading the Bible or other good books.

- Women teachers who marry or engage in unseemly conduct will be dismissed.

- Every teacher should lay aside from his pay a goodly sum of his earnings for his benefit during his declining years so that he will not become a burden on society.

- Any teacher who smokes, uses liquor in any form, frequents pool or public halls, or gets shaved in a barber shop will give good reason to suspect his worth, intention, integrity and honesty.

- The teacher who performs his labor faithfully and without fault for five years will be given an increase of 25 cents per week in his pay, providing the Board of Education approves. (https://www.webstermuseum.org/blog/rules-for-teachers/)

Public policy on teaching was already signaling the expectations and missionary-like dogma sixty years prior to how film and television began to frame teachers. This teacher narrative continues to pervade media’s depictions of teachers, however, unlike the saintly Mr. Chips, some of the more modern twists the teacher as saint into teacher as martyr, e.g., Mr. Keating in Dead Poets Society (1989).

Dead Poets Society’s romanticization of Mr. Keating as a saint/martyr teaching in an idyllic elite boarding school set in 1959 rural Vermont mimics the pastoral musings of the saintly Mr. Chips’ teaching at an elite boarding school in England some thirty years earlier. The teacher as saint or martyr trope romanticizes teachers with the media tending to frame teachers within idyllic private elite schools and settings. Unlike Mr. Chips, however, Mr. Keating’s more liberal aspects of connecting students’ lived experiences to the transcendentalism and romanticism spurred on by poets like Walt Whitman and Robert Frost runs afoul of the more reactionary nature of the private boarding school. When tragedy occurs, Mr. Keating must sacrifice his career for the “greater good” of the students’ future roles of becoming members of the elite social class. Mona Lisa Smile (2003), also set in the 1950s, follows this similar teacher arc with a female teacher, Ms. Watson, transgresses societal expectations of young women at a private, elite liberal arts college. Ms. Watson, like Mr. Keating, must sacrifice her own career as a consequence for leading rebellion against the cultural expectations and roles of women at this time. Films about the 1950s seem to be the romantic starting point where narratives about teachers sprinkle nostalgia for the era while framing teachers as saints who must martyr themselves within the history of progress. This media framing of teachers, however, will shift abruptly during the Civil Rights Era beginning in the late 1950s through to the late 1970s.

From Saints to Saviors: Narratives about Teachers in Response to the Civil Rights Era, 1950s to 1970s.

Interestingly, there are many mediated narratives that idealize education in the 1950s era. At this time, public policy and systemic redlining in urban and suburban areas segregated schools by social class, race and ethnicity. Higher education was limited or inaccessible for many women, people of color, and working-class men. It is ironic that the media tends to romanticize an era of extreme inequity in education. In 1954, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka ruled that racial segregation of public schools was unconstitutional–separate was not equal. The plight of urban, mostly Black and Brown working class people and the schools tasked with educating them now would begin to be depicted in film and television. Unlike the idealized wise teacher who takes vow of poverty for the greater good and to be sacrificed at the altar of progressivism, the media narratives of teachers begin to shift from saint/martyr to the white savior trope. In this framing, the white outsider comes to a chaotic urban school to save the “unwashed” masses inhabiting urban areas. This tale is the same, tired tale of the colonial narratives inherent in the Westerns and “cowboy” movies that framed our conceptions of Western Expansionism. This type of narrative, as seen in the classic westerns of this era, requires a white settler, usually fallen from grace, to tame the “wilderness” and the people, typically depicted as savages, who live in these “wild” lands. If we transpose the settler colonialism myths behind Western Expansionism and Manifest Destiny with impoverished urban centers populated with mostly working class people of color and the teacher as the white savior (settler), the stories become strikingly similar.

Chapters four and six will delve deeper into the legacy of Brown v. Board of Education, however, the impact of this monumental decision shaped how the media framed narratives on schools and teachers. The Supreme Court’s decision has enormous consequences on the schools in communities of color as the era of school integration began. Many teachers of color lost their jobs as the schools in their communities shuttered as policy makers bussed their students to schools in predominantly white areas. These narratives of displacement and loss of community were lost in the romanticism surrounding the 1950s with films like Dead Poets Society and Mona Lisa Smile from the 1980s to the early 2000s. Meanwhile, in the 1950s film and television began in earnest to mythologize the white savior trope in popular culture.

The Blackboard Jungle (1955) stands in contrast to the idealized version of the white suburbia portrayed in popular television shows like Leave it to Beaver (1957-1963) and Father Knows Best (1954-1960). Consider the opening preamble to The Blackboard Jungle:

We, in the United States, are fortunate to have a school system that is a tribute to our communities and to our faith in American youth. Today we are concerned with juvenile delinquency–and its effects. We are especially concerned when this delinquency boils over into our schools. The scenes and incidents depicted here are fictional. However, we believe awareness is a first step toward a remedy for any problem.

Suddenly, in the wake of the landmark decision in Brown v. Board of Education, the media created a spectacle on juvenile delinquency in schools. However, this spectacle could not coexist with the idyllic concept of America developing in the growing suburbs where the public policy of redlining continued to segregate people of color out of the “white picket fence” American Dream. Films and other media like The Blackboard Jungle that create stories about scary juveniles in these dangerous urban areas exacerbated white flight out of urban cities like Detroit, Cleveland, Chicago, and Oakland. The subtext of films like The Blackboard Jungle were more about alleviating white guilt as more affluent, White people abandoned these cities than the manufactured problem of juvenile delinquency. Cities experiencing white flight were now left without adequate revenue streams to fund schools via property taxes. It is easy to explain away racism and classism if there is a perceived, or manufactured threat we must flee from. After all, the media “are effective and powerful ideological institutions that carry out a system-supportive propaganda function…without overt coercion” (Herman & Chomsky, 1988, p. 306). At this time, the media helped manufacture a fear of urban areas and urban youth that can be easily seen in more modern media of our current time.

While most media portrayed urban schools as places overrun by “dangerous” youth, Welcome Back, Kotter (1975-1979), a sit-com set in a public high school in Brooklyn did begin to challenge and subvert mainstream narratives about urban schools, teachers, and youth. In Welcome Back, Kotter, a new teacher, Gabe Kotter, returns to his former school to teach kids tracked into remedial classes. The group of kids in the remedial program are known as the Sweathogs. Mr. Kotter was previously a Sweathog when he was a student at that same high school. Unlike other portrayals of new teachers in urban schools who are typically white, war veterans like Mr. Dadier in the The Blackboard Jungle, Mr. Kotter has grown up and is a member of this community. On the first day of class, his new students, the Sweathogs, welcome him into the classroom with a mural painted on the wall showcasing Mr. Kotter’s membership as a former Sweathog and return to their community. The Sweathogs, like their teacher Mr. Kotter, triumph over the deficit perspectives of the administration, teachers, and students of the school. Welcome Back, Kotter is a welcome reprieve that challenges stereotypes and deficit perspectives of teachers and students.

MEET A SCHOLAR

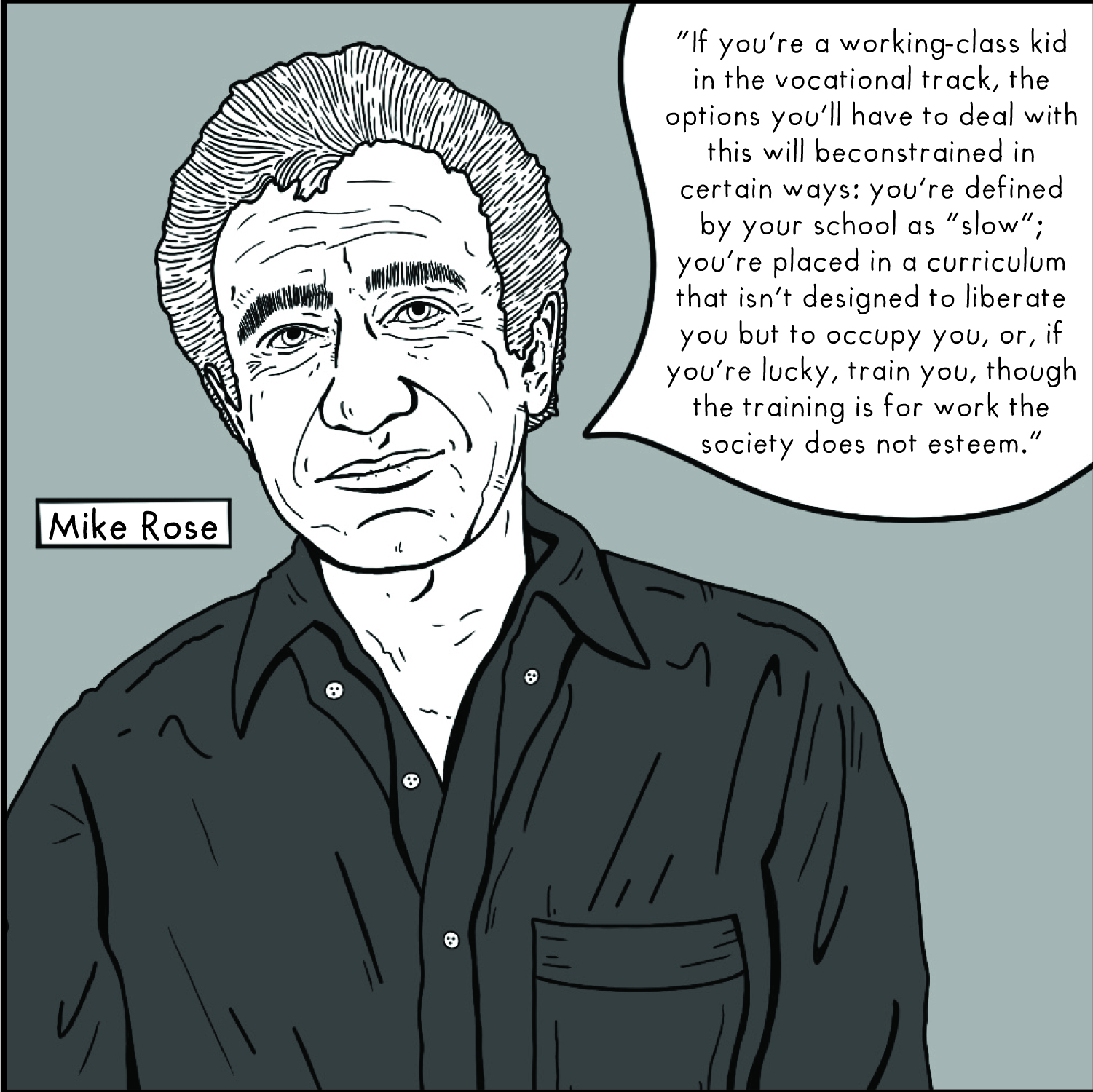

Mike Rose (1944-2021) was a scholar and critic of literacy education and student tracking. As a high school student, Mike Rose was placed on a vocational track due to a combination of a mix up of test scores and his working-class background. One of his high school English teachers advocated for Mike and was moved to the honors or college prep track where he excelled and went on to pursue a career in higher education. As a distinguished teacher educator at UCLA, Rose would go on to become a vocal critic of tracking especially among students from working class backgrounds. Mike Rose would go on to write his seminal autoethnography Lives on the Boundary (1989). In this book, Mike Rose would challenge deficit perspectives and normative definitions of intelligence. He encouraged high expectations and an emphasis on critical thinking for all students rather than remedial curriculum typical of students tracked into vocational education.

Critical Discussion Questions:

- Have you ever experienced being tracked into specific courses based on standardized testing? If so, how did that make you feel?

- What are the implications of tracking on students in terms of higher educational opportunities? Is this equitable?

- What might teachers do to challenge ability tracking to provide more equitable education for students in their classrooms?

From the Quirky to the Profane: Teachers in Film and Television in the 1980s and 1990s

The challenging narrative of Welcome Back, Kotter would erode, however, in the wake of an economic and ideological shift that began during the show’s span on television. In 1983, the National Commision on Excellence spearheaded by the Reagan administration published A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform. This report would dramatically shift federal educational policy towards market-based neoliberalism that still undergirds much of federal education policy. Chapter four will discuss in detail how educational policy shifted from a liberal economic ideology to neoliberalism and its effects on education. One result of the Nation at Risk report is that public discourse began shifting the blame for inequities in education from the material conditions of society like poverty. As the blame shifted from the material, film and television depicted teachers and schools also moved to align with the cultural narratives of teachers proposed by A Nation at Risk report. The report unabashedly framed teachers and their lack of preparation as the primary reason for the “failing” schools. Good teachers, the wise sage of the past generation’s narratives, were now either quirky diamonds in the rough or objects of justified ridicule.

Where Welcome Back, Kotter challenged our perceptions on teachers, students, and the social conditions influencing education, television shows like Head of the Class (1986-1991) flipped the script on the premise of a gifted teacher returning home to reconnect and support students tracked into remediation and failure. Charlie Moore a substitute teacher who has “taught in the toughest high schools in New York City” (Season 1, Episode 1) happens to land a full-time job teaching a group of overachievers in an Individualized Honors Program (IHP).Up to this point, the IHP class worked independently without the need of formal instruction. The substitute teacher, it seems, was there to “just babysit and nothing more,” according to the principal. Instead of a teacher returning to his community and school, a quirky substitute teacher helps socially awkward high-achievers navigate the social norms and expectations of teenagers like asking someone to the dance. Mr. Moore is successful due to his idiosyncrasies rather than professional competencies–he is “just a substitute,” however. The teacher, therefore, must rise above the profane educational system that has failed the youth according to A Nation at Risk. The American ideal of rugged individualism has now infected the discourse on what it means to be a successful teacher. The same students can be seen between when juxtaposing Mr. Kotter’s Sweathogs and Mr. Moore’s IHP students. Head of the Class erases the systemic and material conditions that tracked the Sweathogs into remediation, since it is clear these kids just did not apply themselves to rise out of poverty like the IHP kids. The teacher, then, is irrelevant to society as a whole. Teachers and students must apply themselves individually irregardless of the material conditions of poverty and educational consequences brought on them by food and housing insecurity. If teachers and their students cannot rise above the mediocrity of their peers like Mr. Moore and the IHP students, then teachers and students alike may set themselves up to become objects or ridicule and scorn.

Amy Heckerling’s iconoclastic teen movie Fast Times at Ridgemont (1982) quintessentially captures the shifting ridicule and scorn for teachers and students who fail to apply themselves socially or educationally. While the primary focus of the film is on a hodgepodge of teens navigating the teenage wilderness where parents and caring adults are remarkably absent, two teachers, Mr. Vargas and Mr. Hand, offer tertiary guidance as the students attempt to survive another year at Ridgemont High. Mr. Vargas the zany Biology teacher offers a comic refrain where asks students to “have a heart” as he just switched from regular coffee to Sanka–a decaffeinated instant coffee powder; or, neglects to catch the entire class cheating on a test because he is too focused on solving a rubik’s cube. Unlike the eccentric Mr. Vargas, Mr. Hand serves as the stern, no-nonsense foil to one of his American History students, Jeff Spicoli–a continuously stoned buffoon, who daydreams of surfing and catching a “tasty buzz.” Mr. Hand derides his students for failing testing by dropping exams of his failing students like soiled linen in the hamper. He also makes Jeff Spicoli as an object of ridicule multiple times including a scene where Spicoli enthusiastically orders a pizza to the class so he can have some food and learn about Cuba. Mr. Hand and Spicoli are redeemed on the night of the last dance of the school year. Mr. Hand shows up to Spicolis house, interrupting Spicoli’s plans to go to the dance with his friends. Mr. Hands decided to lecture on all the major topics of his American History class to pay back Spicoli for all the time Spicoli wasted in his class. The two end the spontaneous remediation session amicably with Mr. Hand passing Spicoli in American History.

The absurdity of teaching and teachers in Fast Times at Ridgemont High reflects the premise of A Nation at Risk: Our educational system is failing because of the unmotivated work ethic of the teachers and students. Therefore, in order to save our failing public, policymakers must shift from the traditional liberal education outlined by early educational leaders like Horace Mann in the 19th century or the principles of progressive education developed by Dewey in the early 20th century. While hyperbole in the film, the buffoonish teacher becomes an apocryphal story told by every politician who wants to shift blame for inadequately funding high-needs schools. These policy makers seek to mythologize narratives about absurd teachers who haphazardly socially promote lazy students instead of remediation or removal. Most teachers, then , must become the stern managers tasked with overseeing the mediocre, unmotivated students to ensure financially justifying the institution to taxpayers. However, if a teacher is a brave and idiosyncratic teacher who can challenge students despite the institutional failings of public education as asserted by A Nation at Risk, then that teacher transcends to become the idealized teacher–a return to the teacher as saint/martyr. One film from the 1980s that acutely depicts this phenomenon is Stand and Deliver (1988).

Stand and Deliver (1988) is a biographical account of Mr. Escalante’s inspiring story on how he challenged the institutional and societal expectations of his predominantly Hispanic remedial math student. Mr. Escalante diligently challenged the deficit perspectives of his students and worked tirelessly with his students to pass the Advanced Placement by the end of their senior year. Mr. Escalante’s work is admirable and his story continues to inspire teachers to this day. His story, however, again frames teaching as a saintly calling. Teachers must internalize these narratives where they must sacrifice their identities outside of teaching in order to be successful teaching, especially if their students lack the material and social resources needed to be more successful. After all, Mr. Escalante devoted much of his free time to remediating his students in the summer over the course of several years. The cultural narratives inspired by Mr. Escalante’s success tacitly demands the successful teacher to make up for the lack of material and social support which should be provided by the school system at large. Every year, the tales of teachers buying their students notebooks, pencils, and other supplies is ubiquitous to the point that it is a cultural expectation inherent in teaching. This echoes the expectations of teachers in the 19th century common schools we highlighted earlier in the chapter. This is just the neoliberal transformation of the teacher as saint/martyr.

White Saviors and Martyrs: Mediating Teachers at the Turn of the 21st Century

A key principle of neoliberalism is that limited oversight from the state leads to better economic outcomes. Neoliberalism assumes limited oversight and the fundamentals of the marketplace allows space for competition where those with the best “product” will (theoretically) succeed while the inferior products will fail. In film, we see this in stories of individual teachers who turn a failing classroom or school into a success. This success happens, in most cases, without the support of the school system, or perhaps in spite of it. For example, Dangerous Minds (1995) tells the story of LouAnne Johnson (played by Michelle Pfeiffer), a former marine, during her first year teaching English at an urban high school in California. Her class is primarily made up of low-income students of color, many of whom are in gangs.

The students are initially difficult, taunting Johnson and showing no interest in doing what she asks. However, Johnson finds early success by teaching students karate and offering them extrinsic rewards like candy and field trips. Next, she finds success in teaching them poetry by connecting the work of Dylan Thomas to the lyrics of Bob Dylan. While connecting poetry to her students’ lived experiences can be considered an innovative way to increase student engagement, Johnson explicitly disregards her school’s adopted curricula, often acting in opposition to school administrators and colleagues. The message viewers can take away from this is clear: an individual teacher was successful because she took the initiative to create and try out-of-the-box strategies while the oversight her school attempted to provide would have prevented her success. In other words, innovative individual teachers can be successful if they work against an educational system that is ineffective.

It’s important to note that while Dangerous Minds is based on a true story which Johnson wrote about in My posse don’t do homework, the film portrays her relationship with school administration as more confrontational than it really was. For example, in the movie Johnson argues with the school principal about a book she is required to teach, claiming it is too easy for students; in reality, this book was not required by the school but rather one that Johnson introduced and was later removed after her students chose more complex texts (Lowe, 2001). While we do not know the filmmakers’ intention with this change, portraying Johnson’s relationship with school administration as confrontational does support an individual versus the system narrative.

A similar message, which scholars have described as the “superteacher” (Farhi, 1999) or “hero” (Lowe, 2001) message can be seen in other popular films such as Sister Act 2 (1993) and Kindergarten Cop (1990): an individual teacher is able to make significant positive changes by implementing their own ideas that are often at odds with the school system they are working in. However, there are other important messages within films such as these.

First, these remarkable teachers have no formal teacher training and instead are successful by using their knowledge and skills from previous jobs (e.g., the music teacher in Sister Act 2 was previously a lounge singer, the teacher in Kindergarten Cop is an undercover police officer). These teachers are therefore examples of the outsider/disrupter trope, reinforcing the message that anyone can be a successful teacher (and perhaps oversight of who becomes a teacher, namely state requirements of teacher training, are unnecessary).

Second, urban schools and communities are portrayed as run-down and gang-ridden with parents and students who do not value education; whereas, suburban schools and communities are safe and prosperous with parents and students who value education. Further, as in Dangerous Minds and other films like The Substitute I (1996) and The Substitute II: School’s Out (1998) hearkens back to the white savior of The Blackboard Jungle. In these films the remarkable teacher who finds success in urban schools is white, sending the message that urban schools need a “white hero” (Lowe, 2001) or “white teacher savior” (Cann, 2015) to save them. In doing so, these films exemplify the white savior trope, reinforcing the dominance of Whiteness and position people of color as lacking or deficient. Moreover, the ability of one white teacher to “save” their students or school ignores the very real institutional racism that has led urban schools to be under-funded and under-resourced for decades (Cann, 2015).

The sunny portrayal of suburban communities and schools is also evident in many TV shows from the 1990s, including Boy Meets World (1993-2000), Saved by the Bell (1989-1993), and even The Magic School Bus (1994-1998). Students in each of these shows (generally) attend school regularly and show respect for adults. Issues such as drugs, crime, and family challenges do occur, however they are limited to a specific individual or brief incident (e.g., Shawn in Boy Meets World is the “rebel” character or Jessie in Saved By the Bell struggling with a caffeine pill addiction in one episode) which is a sharp contrast to gangs and violence being portrayed as deep-rooted issues for entire urban school communities.

Regarding teachers, we can see both some similarities and differences in how they are portrayed in TV shows compared to the previously discussed films. For example, while the teachers in these shows all have formal teacher education, they can also be considered heroes due to the profound impact they have on students’ lives. This heroism requires teachers to do more than be innovative in their teaching or push back against the system – they often need to act in ways that are unrealistic or impossible. In The Magic School Bus, Ms. Frizzle uses magic(!) to teach her students, at one point shrinking them to microscopic sizes so they can explore the inside of the human body (Jacobs, 1994). In Boy Meets World, the main teacher, Mr. Feeny lives next door to the show’s main character, Cory; he often offers guidance and life advice when they see each other in their neighboring yards and has a personal relationship with Cory’s parents. Another teacher, Mr. Turner, allows a student to live with him when his parents can no longer provide for him. Here, we see aspects of the martyr trope in that teachers can have a profound impact on students if they go above and beyond the classroom responsibilities expected of them by the educational system. Teachers must be willing to blur the boundaries between their professional and personal lives (or the boundaries between reality and magic) to support students no matter where or when. Furthermore, we see aspects of the wise sage/saint trope, as these teachers are experts in their content knowledge, put the needs of their students first, and always seem to be able to “save the day.”

In both TV and film, we see individual teachers, rather than the broader school system and community, as responsible for students’ learning and well-being. More importantly, we see the message that to be a teacher is to be a martyr because you must be willing to sacrifice your personal boundaries, resources, and passions to always put your students first both in and outside of the classroom. To be clear, this martyr image of teachers is also true in the urban school films discussed earlier, as the challenges the white savior teacher persevered through included spending their own money on supplies, working with students outside of class time, and blurring the lines between their professional and personal lives. However, we could assume this was necessary because of the substantial challenges that urban schools present. But seeing that this is the case for teachers regardless if they are in a tough urban school or a prosperous suburban school shows that all teachers are expected to be martyrs.

The white savior/martyr image of individual teachers persisted throughout the 1990s and continued throughout the 2000s. For example, scholars have discussed how Freedom Writers (2007) echoes the white savior messages of Dangerous Minds (Cann, 2015). However, the 2000s also mark a shift in the seriousness with which teachers are portrayed. While individual teachers can make a difference in students’ lives, these teachers are often lovable buffoons, who act unprofessionally and have messy, silly or chaotic personal lives.

Buffoonery in the Digital Media Age: Teacher Narratives in the 21st Century

While there were always narratives that had buffoonish teachers through most of the era of film and television, these teachers were usually ancillary, side-characters juxtaposed to the serious saint/martyr teacher. Consider the film School of Rock (2003), where a struggling musician, Dewey Finn, becomes a substitute teacher by impersonating his roommate who happens to be a teacher because Dewey desperately needs money to pay his bills. Dewey is not trained as a teacher, yet despite this he is able to secure a long-term teaching position using his charm and skill of deception. While acting as a teacher, he repeatedly behaves in ways a teacher should not: he deceives school administrators, students and parents, does not teach required content, and uses class time to have students form a band and prepare for an upcoming music competition. In the end, however, Dewey has not only won over school administrators and parents but has given his students increased confidence, maturity, and passion; the film ends with Dewey becoming a music tutor.

While such an ending makes for a heartfelt story, the lovable buffoon trope it exemplifies is problematic. First, it closely mirrors the outsider/disruptor trope that anyone can be a teacher, especially those who act in ways that contradict the educational system. Second, the lovable buffoon’s ability to shift the focus of school from developing students’ content knowledge to other activities results in a film that is set in a school where “school” (e.g., learning science, social studies, mathematics, english, art, music, etc.) does not actually take place. In other words, we see school become a place in which activities other than traditional learning are the priority, with no (or very few) images of student learning taking place. This can be seen in other films and TV such as Mean Girls (2004), 10 Things I Hate About You (1999), or Glee (2009 – 2015) where the teachers are messy/chaotic and, while sometimes well intentioned, the students are mostly focused on anything but academics.

This focus away from academics and formal curriculum makes sense when thinking about movie audiences–who wants to watch 90 minutes of someone learning why “the limit does not exist!”? Further, there is a very real argument to be had over what content should be the focus of K-12 schooling–does every student need to learn geometry? However, we must also consider the broader message it sends about teaching and school. For example, is it tenable or effective for narratives set in school to have the central focus of the characters and plot be the place where students are taught the knowledge needed to be effective citizens, skilled workers, and/or change their social position? Or is more tenable or effective to produce narratives about teachers who use the setting of school as an extension of their personal lives (e.g., winning a battle of the bands in School of Rock or writing a novel in 10 Things I Hate About You) instead of teaching students, who in turn prioritize extracurricular activities (e.g., music in Glee) or schemes about their social lives (e.g., romantic relationships, navigating friendships)? The images in film and TV suggest the latter, and together support a broader narrative that the K-12 education system is broken and teachers are part of the problem. Further, if these types of narratives are consumed enough, it is reasonable to see how we, as educators, and the broader public could become skeptical of teachers’ knowledge, their professionalism, and even the importance of K-12 education in general. In turn, this skepticism can impact public attitudes towards things like proposed increases to teachers’ salaries, union protections, or the use of standardized testing to measure teacher effectiveness.

It is important to note that the villain trope, which has been present in film and TV for decades, also contributes to this problematic narrative. The images of Mr. Rooney in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986), Mr. Hand in Fast Times and Ridgemont High (1982), Mr. Vernon in The Breakfast Club (1985), or Sue Sylvester in Glee (2009-2015), portray individuals who do not find joy in their work and appear to consider their relationship with students to be confrontational. As with the lovable buffoon, movie and TV viewers are left to question the professionalism and quality of instruction teachers can provide.

This problematic narrative has unfortunately continued to persist: in Bad Teacher (2011), Cameron Diaz plays a woman who hates teaching and only becomes a teacher after a divorce leaves her in need of money; Fist Fight (2017) focuses on two teachers getting into a physical altercation on the last day of school; teachers in Disney’s Girl Meets World (2014-2017) and Jessie (2011-2015) complain about being underpaid, vocally dislike their jobs, and are often the butt of a joke (Attick, 2016). However, the 2010’s also brought a glimmer of hope as some TV and film began to take aim at other players in K-12 education and even portray teachers in a positive light.

For example, the main character of the sit-com New Girl (2011-2018) is Jessica Day, a trained teacher who cares for her students and is often trying to pull together meaningful learning opportunities for her students. Barriers to those opportunities are not her own buffoonery or problematic students, but issues within the broader educational system such the connection of school funding to agendas of local politicians or the impact of funding on students’ access to technology and the ability to conduct field trips. To be fair, supporting characters do include teacher colleagues who reflect the buffoon and villain tropes; as a comedy, the show certainly has buffoonery. However, the silliness and chaos are part of the quirkiness of the character rather than a detriment to students.

Taking a different approach, a Comedy Central sketch by Keegan- Michael Key and Jordan Peele from 2015 takes aim at the K-12 education system by conducting a teacher draft (Teaching Center, 2015; see references and chapter activity for link)).

Activity:

- Watch the Teaching Center comedy sketch by Key and Peele discussed above: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkHqPFbxmOU&t=1s. Consider the following questions:

- How is this portrayal of teachers different from those seen in tv and movies?

- Why do you think this parody was presented as a sports draft?

- If this was really how teachers were treated, what would the impact be on K-12 schools?

A parody of the NFL draft, the sketch shows an alternate reality in which the neediest schools receive the highest quality educators; in addition, the teachers drafted to these schools are paid millions and receive lucrative endorsement deals. In reality, professional athletes are the ones who receive this treatment while many low-performing schools struggle to find qualified educators (Podolsky et al., 2016) while teacher salaries continue to decline (Walker, 2023). When commenting on a “highlight” video of a high school social studies teacher calling on a student during a discussion, one commentator notes, “See what she did there? She’s bringing an introvert into the discussion, ya’ll. That’s a teacher of the year play, right there.” Another commentator adds, “You know, the confidence gained by [that student] by answering that question correctly will enhance his performance throughout the rest of the year.” This explicit recognition of real instructional strategies that teachers use to engage students is a sharp contrast to the silly or tyrannical methods shown in past media. Overall, this sketch is a clear critique of how our society treats those responsible for educating our nation’s youth in comparison to those who provide entertainment.

Up until now, most examples in this chapter have centered on White teachers. Throughout the decades, there have been some educators of color in TV and film, but these numbers are limited (in part due to issues of representation in media). Such films include To Sir, with Love (1967), the aforementioned Stand and Deliver (1988), and Lean on Me (1989). While these films portray teachers of color as caring and capable, they often tell the story of real individuals (e.g., Stand and Deliver is based on the true story of high school math teacher Jaime Escalante). More importantly, these are teachers who uphold the status quo (Beyerbach, 2005), helping students be successful in the current educational system rather than work to bring about an educational system that is more equitable and socially just.

The TV series Abbott Elementary (2021-current) may be considered a recent, and notable, step in how teachers are portrayed in popular media. The show follows a group of mostly Black educators as they navigate the Philadelphia public school system (the show is shot as a mockumentary like The Office). The focus on a diverse group of educators is a significant shift. What makes it more notable is that a primary source of conflict is the educational system (e.g., inept administrators, limited funding, insufficient district professional development; Principal Ava is… Not quite helpful, 202) rather than the teachers. In fact, conflict resolution usually occurs when the teachers come together in solidarity to support one another. For example, in the clip cited above (see reference and chapter activity for link) Janine is unable to get her classroom rug replaced by the district when her principal spends the allocated funds on a new school sign. In the end, her colleague Melissa gets new rugs through a “friend” outside of school. Here we see some buffoonery as it is implied that Melissa’s “friend” works construction and stole the rug from his job renovating the Philadelphia Eagles stadium, but as with New Girl the buffoonery is part of a character’s comedic quirkiness and not a detriment to the students.

Activity:

- Watch the following clips from Abbott Elementary. Describe how the teachers and administrators are portrayed in these clips.

- Principal Ava is… not quite helpful: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PqWuTK6JkUs

- Barbara and Melissa give Gregory teaching advice: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_RObnudYWk8&list=PLRy6W5nz84Qbg7JndWxc5pV4PoWFLzgBt&index=4&t=1s

- Compare and contrast this portrayal of teachers and administrators to those previously discussed in the chapter. Come up with at least two similarities and two differences.

The theme of teachers helping teachers is a constant throughout Abbott Elementary. Another example can be seen when teachers Barbara and Melissa offer advice to Gregory who is struggling to teach math. What is notable about this clip is that not only do Barbara and Melissa help Gregory, but they do so without placing blame on students or advocating for lecture-based instructional methods; they position students from an asset-based perspective by explaining the importance, and sensibility, of what students think and offering ways to make learning more fun. Thinking back to how teacher-student relationships were portrayed as confrontation in past media, this is a stark contrast.

Abbott Elementary also takes on other issues in K-12 education. Explicit conversations about teacher Jacob’s identity as a “woke,” gay, White male teacher in a predominantly Black school acknowledge the reality of white savior-ism. A gifted and talented program leads to discussions of how tracking negatively impacts student identities and classroom dynamics. Efforts to turn Abbott and nearby schools into charter schools reveal why charter schools are not the magical solution they are often portrayed to be legacy media and political discourse; charter schools are not legally required to accept all students, often employ uncertified teachers, and are funded with dollars that would otherwise go towards public schools.

Overall, the message from Abbott Elementary is that the K-12 education system is far from perfect but that teachers are not to blame. Instead, teachers are often fighting an uphill battle against issues that can only be addressed at the systemic, or even legislative, level. It is no surprise that teachers reportedly “feel seen” by Abbott Elementary (Juhasz, 2023). We, as educators, look forward to seeing more narratives about schools, teachers, and students that challenge or subvert the harmful narratives of teachers and youth depicted by popular media in the past.

Why this matters

This chapter is grounded in the idea that the media helps construct cultural narratives and beliefs about teachers and teaching and these narratives shape how we see ourselves as teachers and our students. But why is it important that you develop this critical lens and view media differently? First, as this chapter has shown, learning more about the dominant narratives found within media allows you to view media through a different, more critical lens. That is, we, as educators and critical consumers of media, need to see media as not just entertainment, but also think about the message it sends about those it portrays. We encourage you to watch any of the different TV shows or movies discussed throughout this chapter to “see” the different narratives we discussed (that’s right – you college textbook is telling you to go watch TV and movies!). You may be surprised at the new things you now notice. Second, you can use this lens to critically reflect on your own beliefs about teachers and teaching. Such reflection will allow you to think about how your actions as a (future) teacher push back on, or perpetuate, the problematic narratives discussed here. And finally, it can help prepare you for how others who are not educators, but consume such popular media, may view you once you become a teacher. It will not make it less frustrating when someone downplays the amount of time and effort it takes for you to prepare an engaging lesson, for example, but at least you will know such a view has been shaped by decades of media.

Post-Reading Activities and Consolidating Understanding:

- Watch a movie that, at least partially, takes place in a school. Identify the teacher trope(s) you see, including the evidence you used to make your identification, and what message(s) about teaching, school, and students the movie is sending. Analyses can be shared as an argumentative essay or presentation.

- A key argument of this chapter is that images in the media shape our understanding of teaching, school, and students. For this activity, go interview three people and ask them what they think about teachers and K-12 education. Then ask them what movie/TV teachers are memorable to them and why. Reflect on any themes, connections, or other notable findings from your interview.

- Teaching is not like it is in film and television as this chapter argues. There are many steps to becoming a licensed, professional teacher. The following list outlines the requisite steps necessary to become a certified teacher in the state of New York, however the steps are not in chronological order. Research the requirements one needs to obtain your initial teaching license and put these steps in chronological order. Different states have different requirements for teacher licensure. However, the steps in Appendix A are very similar to other states’ pathways to becoming a teacher. After reorganizing the steps chronologically, map out your own progress in becoming a teacher as many of these requirements begin very early in your teacher education program. In class facilitators may use this outline as an in-class collaborative remixing or jigsaw discussion activity. The answer key is located as an appendix at the at of the chapter.

Steps to Obtaining New York State Professional Teaching License

- Complete and log your professional development hours yearly on TEACH; this is needed for recertification.

- Complete all three workshops: SAVE, Mandated Child Abuse Training and DASA.

- Meet all of your non-degree requirements (such as maintaining a 3.0 average in your education classes).

- Be recommended for certification by your college.

- Successfully complete student or clinical teaching.

- Find and apply to a master’s degree program that will lead to professional certification in your area of initial certification.

- Ask for and collect good letters of recommendation from your cooperating teachers and supervisors.

- Complete all degree requirements and apply to graduate.

- Apply to graduate and obtain your master’s degree within 5 years.

- Complete the master’s degree program successfully.

- Apply to and get accepted to a college with an accredited education program.

- Complete three years of teaching successfully.

- Apply for initial certification through NYSED – TEACH.

- Complete at least 100 hours of early field experience.

- Interview and secure a job in your area of certification.

- Apply for Professional Certification through NYSED-TEACH.

- Successfully complete TPA assignment during student teaching.

- Pass all certification exams (CST & EAS).

- Complete the fingerprinting process.

- Take and pass all the general education requirements as stated by your college.

- Graduate with your bachelor’s degree.

- Apply for a job in your area of certification.

- Complete all of the coursework required by your education program, including pedagogy, educational psychology, literacy and methods.

- Create a TEACH account at NYSED

Glossary

Asset-Based Perspective: A way of viewing students through their strengths and the funds of knowledge learned in their communities that they bring into the classroom. These funds of knowledge are seen as positive assets. This perspective contrasts a deficit perspective of students.

Deficit Perspective: A way of viewing students, typically from historically marginalized communities, as solely responsible for the challenges they experience in education. This perspective blames the student, parenting, and upbringing rather than the oppressive structures and policies that created these challenges in the first place. Teachers who say, “my students can’t do this or that, because they need these remedial skills first,” or “there families just don’t value education,” are complicit and replicate a deficit perspective upon their students.

Extrinsic Reward: A tangible, external reward visible to others. These rewards can be material like food (candy) or immaterial like stickers.

Frame: The way a communicator constructs and communicates a message in order to highlight, obscure, or hide some aspects of the message over others.

Hidden Curriculum: Unwritten lessons, values, prejudice, or perspectives on students and learning created in the formal curriculum.

Hegemony: The systematic maintenance of oppression of a group or groups of people over another for the purposes of exerting dominance–ideologically, socially, politically, or economically.

Neoliberal(ism): A political and economic ideology that advocates for deregulation of the free market. It advocates for privatization of the public commons, like schools or other public infrastructures, because it assumes that privatization is more economically efficient than nationally or locally run public entities.

Trope: A figurative use of a word, expression, or convention that is nonliteral and connects to more abstract concepts or ideas. Metaphors and similes are types of tropes.

Figures

Roland Barthes by Natalie Frank is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

Mike Rose by Natalie Frank is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International

References

Attick, D. (2016). Images of teachers: Disney channel sitcoms and teachers as spectacle. Counterpoints, 477, 137–147.

Barbara and Melissa give Gregory teaching tips. (2022). ABC. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PqWuTK6JkUs

Barthes, R. (1957). Mythologies. Hill and Wang.

Beyerbach, B. (2005). The social foundations classroom: Themes in sixty years of teachers in film: Fast times, dangerous minds, stand on me. Educational Studies, 37(3), 267-285.

Cann, C. N. (2015). What school movies and TFA teach us about who should teach urban youth: Dominant narratives as public pedagogy. Urban Education, 50(3), 288–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085913507458

Dunbar-Ortiz, R. (2014) An indigenous peoples’ history of the United States. Beacon Press

Farhi, A. (1999). Hollywood goes to school recognizing the superteacher myth in film. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 72(3), 157–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098659909599618

Harper, C. A.. (1939). A century of public teacher education; the story of the State teachers colleges as they evolved from the normal schools. Pub. by the Hugh Birch-Horace Mann Fund for the American Association of Teachers Colleges.

Herman, E.S., & Chomsky, N. (1998). Manufacturing consent: the political economy of mass media. Vintage Books USA.

Jacobs, L. (Director). (1994). Inside Raphie (3). In The Magic School Bus.

Janak. (2019). A Brief History of Schooling in the United States From Pre-Colonial Times to the Present (1st ed. 2019.). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-24397-5

Juhasz, A. (2023). How “Abbott Elementary” helps teachers process the absurd realities of their job. Npr. https://www.npr.org/2023/04/07/1156532261/philadelphia-teachers-abbott-elementary-school

Lowe, R. (2001). Teachers as saviors, teachers who care. In P. B. Joseph & G. E. Burnaford (Eds.), Images of schoolteachers in America (2nd ed., pp. 211–227). Lawrence Erlbaun Associates.

Podolsky, A., Kini, T., Bishop, J., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2016). Solving the teacher shortage: How to attract and retain excellent educators. Learning Policy Institute.

Small, W. H. (1914). Early New England schools. (W. H. Eddy, Ed.). Ginn and Co.

Teaching Center. (2015). Comedy Central. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dkHqPFbxmOU&t=1s

Tyson, L. (2015). Critical theory today: A user-friendly guide. Routledge.

Principal Ava is… Not quite helpful. (2021). ABC. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PqWuTK6JkUs

Walker, T. (2023). Teacher Salaries Not Keeping up with inflation, NEA report finds. Nea Today. https://www.nea.org/nea-today/all-news-articles/teacher-salaries-not-keeping-inflation-nea-report-finds