4 ReStorying the History, Policies, and Places of Public Education

Thor Gibbins

Before We Read

Anticipation Guide

Read each of the following statements. Put a check under “Agree” or “Disagree” to show how you feel about each statement. If possible, discuss your responses with peers.

| Statement | Agree | Disagree |

|---|---|---|

| Puritanism heavily influenced education during the Colonial Period. | ||

| The primary goal of public education is to educate young people to assimilate under a cohesive national identity. | ||

| Every school in the U.S. receives an equal amount of funding regardless of geographical locale. | ||

| Textbook and testing companies significantly influence educational policy and curriculum. | ||

| Failures of public education are a result of teachers and teacher education programs. |

Critical Question for Consideration

As you read, consider these essential questions: What have been the goals of public education throughout the history of the United States? How have these goals changed? In what ways does each goal support or challenge the other goals? To what extent do private interests influence public education funding and policy? In what ways does geography shape public education locally?

The goal of this chapter is to give a historical overview of public education in the United States from its colonial period to our digitally connected world. However, this overview is not without its own critical framing. Critical questioning entails an interrogation of power and the distribution of resources, i.e., politics, in terms of who benefits and who becomes marginalized from the system designed to oversee the implementation of power and the distribution of resources including education. This requires an investigation outlining public education as a part of a system that has been in continual transformation. Therefore, this chapter will involve a critical analysis of the role of public education in the Americas from settler colonial America, the development of the nation state of the United States, western expansionism, and the neoliberal transformation of the United States as the global economic power in the 20th and the first quarter of the 21st century.

In order to help frame this analysis of change in a way that might illuminate the more hidden, systemic structures of how public education has been implemented and maintained, I will use a combination of historical and material frameworks for analysis: the first framework is educational historian David Labaree’s (1997b) more overt and alternating goals of education and Jean Anyon’s (1980) social class analysis which reveals the hidden curricular and problematic goals that underlie the more overt goals. In addition to the hidden curricular goals, there are also hegemonic goals of assimilation and erasure latent in the establishment and maintenance of public education. These goals are complex and nuanced and, at times, are contradictory. Hence, the goal in outlining these frameworks (see Table 4.1) is to analyze the contradictions inherent in the differing goals of education in order to recognize and diagnose problems within education. It is crucial for us, as teachers and as agents within the system of public education, to help redirect the course of public education for more equitable access to high, quality public education for all students.

| Goal | Explanation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Democratic Equality (Public Good) | Our public schools should steward effective citizenship, equal treatment, and equal access for all students. | A major argument for liberal arts education is to ensure all members of a society should have familiarity with a wide range of content areas and topics in order to prepare students to help solve challenging social issues. |

| Social Efficiency (Public Good) | Our economic well-being as a society posits public schools need to prepare our youth for useful economic roles competently. | In the late 1950’s, The National Defense Education Act sought to train students for a variety of jobs like engineering and science to compete nationally with the Soviet Union. This led to ability tracking which involved more hidden curricular goals like social reproduction or the workforce. |

| Social Mobility (Private Good) | Education is a private commodity and public schools should provide individual students with a competitive advantage in selling their labor to achieve more desired social positions. | In order to gain competitive edges for individual students to gain admissions to competitive colleges and universities, Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate programs were developed in high schools. Most of these programs are gatekept through standardized testing or access to resources afforded by affluence. |

| Social Reproduction (Hidden Curriculum) | When examining the teaching and work practices of classrooms from schools teaching students from different social class backgrounds (working class, middle class, affluent professional, and executive elite), the types of classroom tasks given to children from these different schools reveal a hidden curriculum of assimilation and social reproduction. and social reproduction children are given work tasks that mirror the types of tasks of their parents or caregivers: unskilled labor, skilled labor, managerial, professional and creative, and executive tasks expected of political or economic leaders. | Based on Jean Anyon’s (1980) observational analysis of 5th grade math classes and work tasks five different schools (public and private) that served children from different social classes (working class, middle class, professional managerial class, and executive elite class):

|

| Assimilation & Erasure (Hegemony) | Assimilationist policy is a form of ethnic, linguistic, or cultural erasure typically forced upon historically marginalized communities: children of color as well as white, working and/or underclass children from rural geographies. | In the late 19th century and up until the l970s, government agents took, many times by force, Indigenous children from their homes and community to residential and boarding schools. These children were severely punished for speaking their native languages. They were forced to dress in Eurocentric fashions. |

Think-Pair-Share Discussion

Team up with a partner, look over the table of goals of education, and use the following questions to help guide your conversation:

- What type of educational experiences might you have had that connect to one or more goals?

- Have you had any other experiences that may have been contradictory to any of these goals?

Join another pair of discussants and compare your experiences and connections.

Colonial Education

In its inception, the development of public education was an extension of European colonialism in the Americas with the forced displacement and erasure of the Indigenous nations, cultures, and languages. British colonialism shaped the direction of public education in Colonial America where the Puritan, or Calvinist, theological worldview of the early British settler-colonizers significantly shaped education. Much like the political makeup of each colony, especially in New England, the purpose of education centered on religion.

In colonial New England, the first public and private schools served mostly boys from merchant and other upper class backgrounds. In 1642, the Massachusetts Bay Colony made education compulsory (i.e., required). These first Latin grammar schools were formed to serve boys born into wealthier social classes in their preparation for university, which were the elite Ivy League institutions that had recently been founded in the new colonies. By applying Labaree’s (1997b) goals of education, we can clearly ground education at this time as a private good only available to the landed gentry emerging as the ruling class in the American colonies. By limiting access to education to men of European descent born in social positions of power, colonial education was inherently undemocratic and sought to limit educational opportunities for women, sustenance farmers, tenant farmers, indentured servants, slaves, and Indigenous peoples for the purposes of oppression and the exploitation of their physical, creative, and emotional labor, i.e, for the purposes of hegemony.

While the elite social classes created educational structures to limit access to education, the Puritan settlers who founded the Massachusetts Bay Colony did make literacy a priority. More specifically, they made reading a compulsory part of the head of household duties to ensure all children in the household were able to read the Bible and other religious documents (Janak, 2019). Basic literacy skills, then, “opened” up education beyond the landed elites; however, the purpose was solely on being able to read the bible and not for either participating in democracy or for social mobility. Most education at this time was public; however, as Janak points out, while education was open publicly, formal schooling was only available to those that could afford it. For those that could not afford formal schooling, basic literacy education involving reading and writing was either done informally in the home or at church.

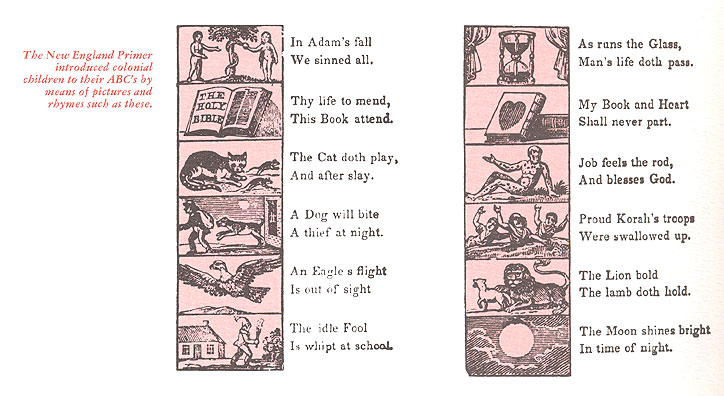

Most literacy education in the colonial era was dedicated to preparing people for reading the King James version of the bible, a version of the bible favored by Protestant branches of Christianity. Primers like the New England Primer focused primarily on basic phonics of letter-sound relationships, consonant blends, digraphs, and rote memorization of rhymes using similar phraseology used in the King James Bible.

The primary goal for educating youth, then, was toward a Puritan worldview which required stern control of children in preventing moral depravity and subsuming the self in submission to God’s authority.

Early Federal Era, Western Expansionism, and The Haunting Legacy of The Indian Removal Act

After the American Revolution and subsequent War of 1812, the project of developing and maintaining a new nation state began in earnest. There was keen interest in developing a means of public education for a new nation emerging from newly garnered independence from the British Empire. However, despite this new independence, most of the ideas for public education stemmed from the English system of education (Janak, 2019). The Enlightenment and Reformation periods heavily influenced the English system of schooling, and, likewise, the burgeoning public school system in the early period of the United States. Moreover, since the Enlightenment philosophers took their primary inspiration from the Occidental traditions born from ancient Greece: chiefly Platonic idealism and Aristotle’s realism and empiricism. These traditions formed the basis of liberal education in European universities and the elite colleges and universities founded within the colonial period in the Americas.

Idealists like Thomas Jefferson wanted to set up a meritocratic system of education to cultivate future “philosopher kings” to continue leading the new Republic. Jefferson advocated for public primary schools and grammar schools where “commoners” could compete for free tuition at elite institutions. Because this public access of “commoners” was limited to white males of certain social classes, the romanticized ideal of American meritocracy was already a myth even at these early stages of Federalism. Jefferson labeled his burgeoning meritocracy of publicly funding access to higher education as a policy for “raking the rubbish,” an obvious classist and elitist appraisal of working-class groups. Jefferson’s intention for this “meritocracy” was to weed out low-performing students from lower socio-economic groups and reward 10% (one out of 10) of the students with pensions to attend universities. Despite his clear disdain for the working-class citizenry, Jefferson’s idealism did lead to the establishment of public universities like the University of Virginia and the State University of New York system (Janak, 2019). This is also the beginning emergence of two alternative goals of public education (Labaree, 1997b): democratic equality and social mobility, albeit severely limited in terms of equitable access for all. This push for a more robust public system of education also led to the need for a more formally trained cadre of teachers, who had been primarily parents and other familial caregivers in the colonial period leading up to this federal era.

Teacher Training and the Formation of Normal Schools

In the 19th century, there was a confluence between the religious goals of public education and the idealists’ need for a more educated citizenry capable of maintaining the new republican democracy in the newly founded United States. This merger led to the establishment of common schools in the Northeastern U.S. Common schools were local communities funded projects to support educating the youth in each particular community. Funding for common schools relied upon wealthy benefactors in the community as well as the local clergy (Smith, 1914). Because of this, the common school, while publicly available to youth in a community, were not democratic institutions. The wealthy benefactors and clergy determined the curriculum for the school as well as who were hired as teachers in the school. Therefore, the primary decision makers needed to find people in their community who would be willing to take directives without creating problems to either interests of wealthy elites or the authority of the different Protestant churches established in these various communities. Teachers, then, were recruited from groups who held significantly less social and political power who would be willing to take “modest”, or low salaries. These new cadres of teachers were mostly unmarried women from working class backgrounds. Even in public education’s infancy, the teaching profession was exploitative and feminized in order to find a workforce willing to teach for low wages and could not exercise agency in making curricular decisions that would challenge or subvert the local authorities’ power. This is not to say that common schools and the development of more standardized normal schools designed to train public school teachers were totally undemocratic; these schools did arise from electoralism and people elected into positions of political power. The political positions, however, did tend to be held by people coming from the social elite and ruling classes, which is something that still persists to this day.

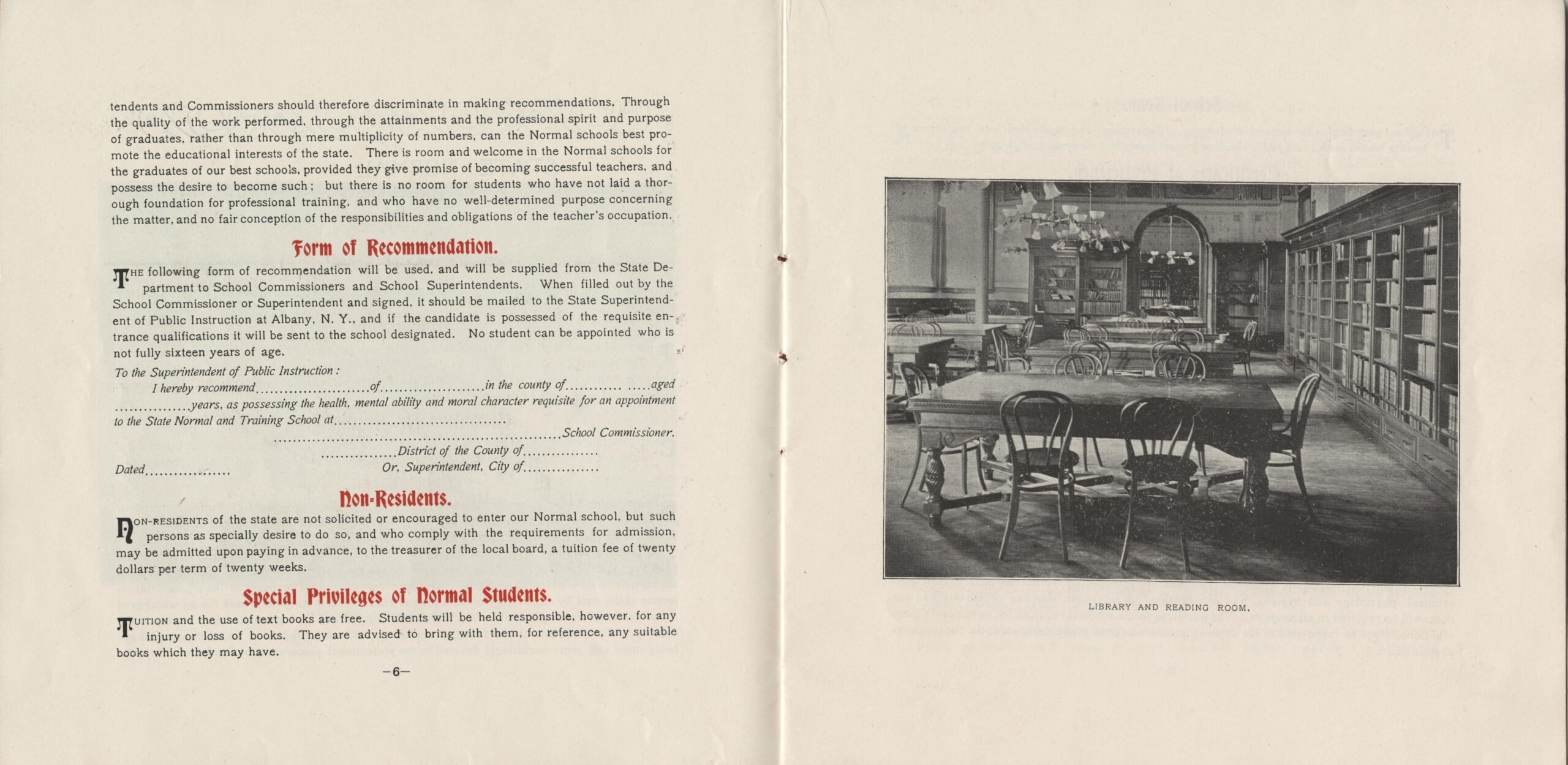

Because each community had disparate community needs for educating the youth in their particular area, common schools had varying curricula. In Massachusetts, Horace Mann became instrumental in the establishment of common schools. At this time, Mann sought to standardize the curriculum across the state of Massachusetts. This led to Mann submitting annual reports to the Massachusetts Board of Education over a ten year period from 1838-1848. Mann’s standardization effort led to the establishment of normal schools that would formalize the teaching and training of teachers (Harper, 1939), which was also a need for other skilled labor positions during the rapid industrialization taking place in the mid-19th century. The Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890 granted federal lands for colleges that would teach skills needed for positions in education, agriculture, engineering, and other skilled-labor professions. The growing need for a skilled workforce to carry forth the rapid industrialization, as well as Western Expansionism’s thirst for new natural resources for energy extraction, began another alternative goal for public education–social efficiency. Industrialization required wealthy owners of private businesses to finance or support endowments to train a workforce to meet the labor demands of the shifting labor market. Hence, the emergence of land-grant universities and colleges emerged in response.

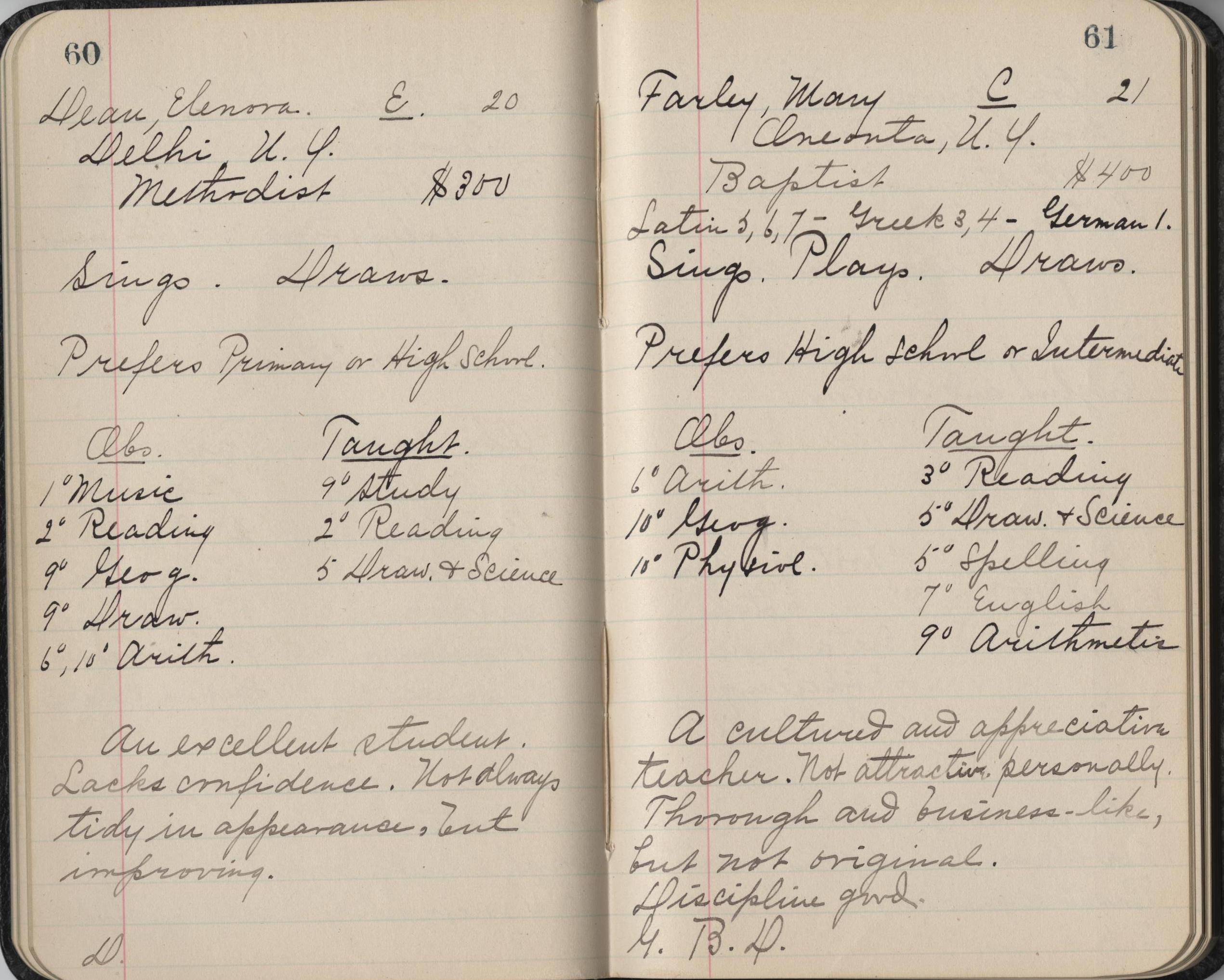

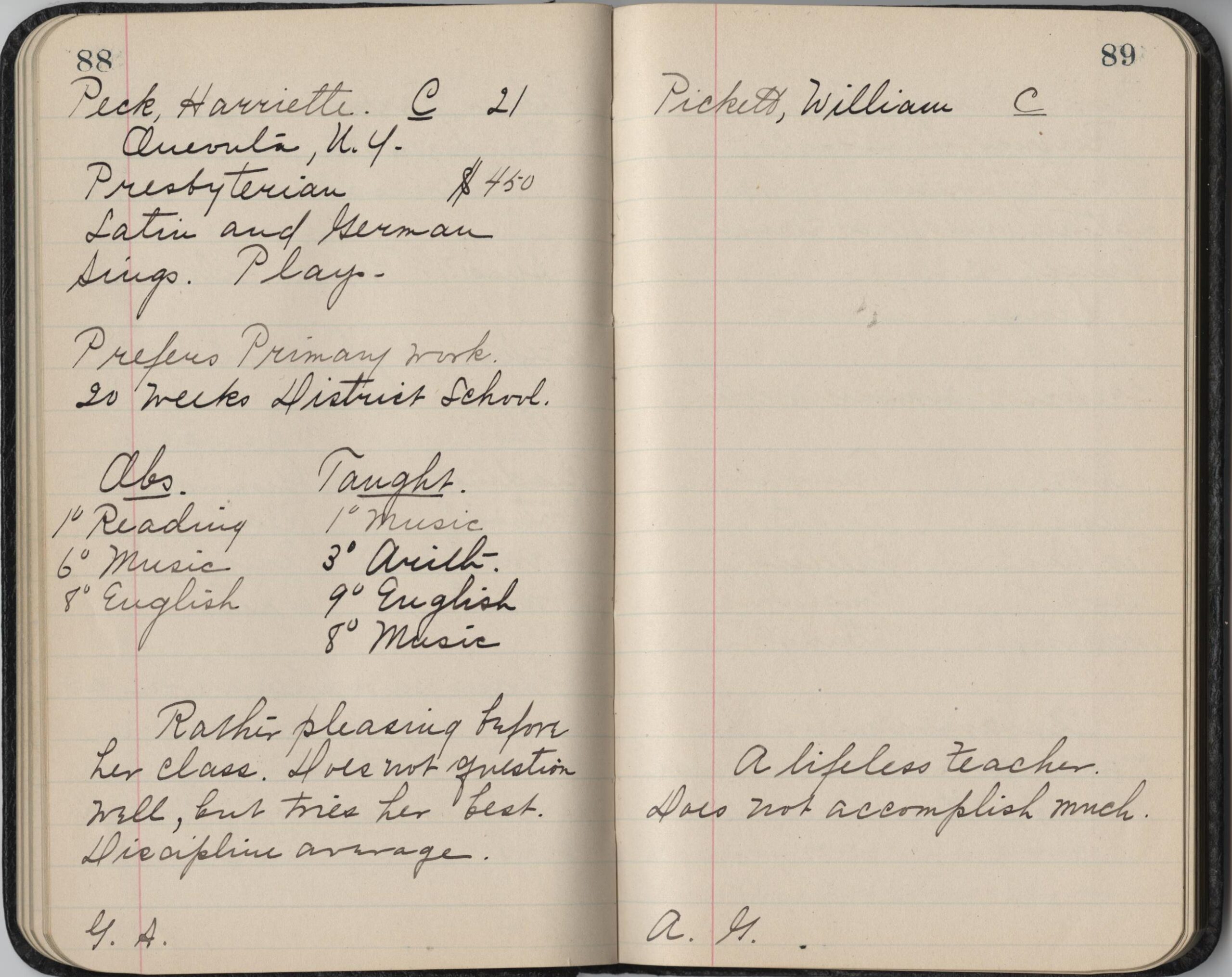

Normal schools, which would resemble somewhat a contemporary high school consisting of grades 9-12, trained 15-to-18-year olds to teach in public schools, which at the time spanned grades 1 through 8. Teacher training at normal schools focused primarily on teaching basic literacy skills in reading and writing in addition to arithmetic, gymnasium (physical education), drawing, and basic sciences–all subjects consistent with a liberal education. A close examination of student teaching observations (see figures 4.3 and 4.4) reveal terse commentary on actual pedagogy, but, rather, focused more on gender, religious affiliation, and traits like physical attractiveness. What, then, were the educational goals for teacher training at this time? It does not appear to be highly focused on pedagogical theory, which had not been really developed at this time, but more on training teachers who could effectively maintain control and manage children. In terms of the hidden curriculum, public schools, much like today, functioned as a means of social reproduction for unskilled or skilled labor needed in each community. Normal schools, however, were a mechanism for social class mobility for youth–mostly young women–from the working class to access higher education beyond an eighth grade liberal arts education. Affluent youth, at this time, had the material resources for them to attend private, preparatory schools, which allowed access to the elite colleges and universities with the purposes of training the next generation of doctors, lawyers, or other professions needed for maintenance and allocation of social and political power for elite social classes.

Listen

A series of audio recordings of Horace Mann’s annual reports to the Massachusetts Board of Education (https://archive.org/details/annual_reports_mass_board_of_education_mk_1808_librivox/annualreportseducation_47_mann_128kb.mp3). Horace Mann’s Twelfth Annual Report from 1848 is of particular note. Listen to episode 47, which is part 2 of Mann’s Twelfth Annual Report, and take notes on the following guiding questions:

- What are the terms and phrases that Mann uses that create a narrative to support a democratic equality goal of education? Are there any that could connect to narratives for social efficiency or social mobility goals of education?

- What fields of study does Mann argue should be the focus in public schools? Why these particular content areas?

In addition to the formation of normal schools to train teachers for the expanding public elementary schools, the Morrill Acts of 1862 and 1890 initiated federal policies for states to create public, land-grant universities. In response to the Industrial Revolution, there was a growing need for more skilled labor in terms of engineering and energy extraction (e.g., rail and transportation, mining, oil drilling, etc.). Public land-grant universities served as points of service for educating a technically skilled workforce required for these growing industries. Clearly, the public goal of developing the low or no cost colleges, universities, and normal schools was shifting the early federal era’s goal of educating the citizenry for democratic participation to a more utilitarian social efficiency goal. Of particular note, as a part of Reconstruction Era following the Civil War, Historical Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) were born as land-grant universities to serve the African American population recently emancipated from the horrors of chattel slavery. Federal policies, however, never equitably funded HBCUs in comparison to the state land-grant universities, most of which were state and local Jim Crow laws racially segregated and barred children of color from matriculation. Even when the goals of public education began to expand to be more inclusive in the public and private goods, there have been hegemonic goals to limit working and under class access to social and political power while constructing a stratified racial caste system.

Western Expansionism and Education

In addition to using federal policy toward enclosing public lands as sites for land-grant colleges and universities, these policies also served as mechanisms to displace First Nations peoples from their ancestral homelands. The Morrill Acts served as a less genocidal continuation of federal policies directed toward the Indigenous peoples instigated by the Indian Removal Act of 1830. The Indian Removal Act authorized the U.S. military to forcibly displace the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Seminole, Cherokee, and Creek nations from their homelands in the Southeastern U.S. The ideology of Manifest Destiny and the policies of displacement like the Homestead and Morrill Acts provided the blueprint for a new wave of settler colonialism embedded in western expansionism that sought to displace Indigenous people and enclose these lands either as public sites for conservation and education or as privately owned land to be parceled out and sold by land speculators. These policies clearly intend to legitimize the systematic erasure of First Nations peoples.

As U.S. settler-colonialism expanded west, there was a significant need for schools to give children of settlers a place to learn basic literacy and numeracy skills much like in the common schools in the North and Southeast. This also required a workforce of teachers to serve in these communities and schools out west. Unmarried women were recruited as teachers to teach in one-room schoolhouses as the political borders of the United States continued westward toward California. Women at this time did not have rights of suffrage or the right to own property. Therefore, female teachers found themselves in continuously tenuous positions with limited authority or decision making powers regarding curriculum and methods of teaching. Moreover, female teachers had to give up teaching if they were to marry. Just like the common schools, political power for making educational decisions was given to local community leaders–wealthy men and clergy. Even in its beginnings, teacher agency in making curricular decisions was severely limited. With the political power of educational decision making consolidated to ruling and professional managerial classes, policy and goals for educating the masses were easily maintained and controlled to protect the political and social power of the elite. However, this would change somewhat as women began to organize and resist their own oppression at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Female teachers were at the forefront of the women’s suffrage movement as well as the labor movement to unionize teachers. Teacher agency and professional autonomy is still a primary focus of teacher activism and will be discussed in a later chapter. Empowerment and emancipation from hegemonic systems is an ongoing process. We, as educators, owe a tremendous debt to these brave educators who strived to educate their students at the same time fighting against their own exploitation and oppression.

The Trauma of Residential & Boarding Schools for Indigenous Children

As the U.S. expanded its political territories west and in response to over two and half centuries of Indigenous displacement and genocide, First Nations peoples, notably the Lakota, Dakota, Nakota nations in the mid-west and the Apache and Comanche nations in the southwest began waging a guerilla-style insurgency in resistance to the waves of settler-colonizers beginning to expropriate and occupy their lands. For the U.S., continuing a protracted war with insurgents from hostile nations who have been systematically displaced from the homelands became tenuous. The practice of isolating and concentrating Indigenous peoples away from the growing settlements was unsustainable as the privatization or public enclosure of land would make the growing western territories akin to a pseudo-apartheid state, which would, much like modern-day apartheid states, require a significant amount of military force to continuously occupy and oversee the submission and complacency of the displaced First Nations peoples. Therefore, another form of pacification was needed–an educational system designed to assimilate the Indigenous population into the political economy of the U.S.

One of the earliest forms of pacification through education was the Spanish mission system, which was the Spanish colonial model. Spanish colonizers set up missions as a way to force conversion to Catholicism and then exploit Indigenous labor to extract resources from the Americas to be brought back to Spain. Mission schools were set up by Catholic religious orders to indoctrinate and convert the Indigenous peoples of South, Central, and Southwestern regions of North America. Protestant mission schools were also established in the British colonies like the Massachusetts Bay Colony who demanded First Nations peoples assimilate into the Puritan cultures and Protestantism of the European settler-colonizers (Szaz, 1999). In the 19th century, the mission school system morphed into Native American residential and boarding schools as the U.S. military stepped in as the primary overseer for educating children from the plethora of First Nations people now being occupied by the U.S. military in enclosed reservations.

Richard Henry Pratt, a lieutenant in the U.S. Army, established the Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Carlisle, Pennsylvania in 1879. The explicit goal of the Carlisle Indian School was to “civilize” and assimilate Indigenous children so that they would have no desire to return back to their nations and reservations. Standing Bear, a student of the Carlisle residential school and future Oglala Lakota chief, recalled that, at Carlisle, he “went to school to copy, to imitate; not to exchange languages and ideas, and not to develop the best traits that had come out of uncountable experiences of hundreds and thousands of years living upon this continent” (p. 237). Language instruction was one-way at these residential schools. In fact, teachers severely punished students by speaking their native languages or practicing integral parts of their culture like First Nations dances and ceremonies. The Religious Crimes Code of 1883 explicitly sought to punish and imprison anyone outwardly practicing their Indigenous cultural identities. This code was amended in 1933 to lift the ban on some of the First Nations dances; however, ceremonies like the Ghost Dance (which sparked the Wounded Knee Massacre in 1890) and the Sun Dance were illegal with the threat of incarceration until the federal government repealed the law in the late 1970s.

Boarding and residential schools became the primary mechanism to displace Indigenous children from their parents and communities throughout the end of the 19th century and most of the 20th century up. Boarding schools like the Phoenix Indian School became a mechanism to displace children from their homes and place them as low-cost servants in wealthy white households (Reyhmer & Eder, 2017). This seems to be, then, government sanctioned child trafficking for the benefit of the social and political elite. There were federally funded reservation schools governed by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. However, residential schools were significantly underfunded with dire outcomes for children attending these schools. These schools framed education from Western, Eurocentric framing and purpose was seen by First Nations leaders as primarily vocational training for a workforce rather than to “create good human beings who live a balanced life” (White, 2015, p. 167). It is not surprising that children who come from communities with a different orientation toward the world and pedagogy would suffer. It was not until the late 1960s and 1970s when Indigenous leaders, teachers, and activists began a committed campaign for self-determination for First Nations communities to change education for their children.

Cordova (2007) explains that for First Nations children the family is not only the “nuclear” family defined by Eurocentric standards, but all members of the community:

The “community” includes not only the family but the surrounding environment. One learns to be aware of one’s actions and their consequences toward other people but toward the “ground” one inhabits. There is an assumption about what it is to be human that underlies all of this training of how to be human (p. 81).

The embodied alienating experience Indigenous children feel when they enter what Cordova describes as a “parallel universe” where “the trees, the mountains, the air–the physical place–may be the same; the philosophical is not. In order to counter these acute and harmful effects on Indigenous children, Indigenous parents, teachers and activists designed survival schools to counteract these symptoms of extreme disorientation. One survival school is the Akwesasne Freedom School which was established in 1979 on a reservation in New York State. Mohawk is the primary language of instruction and all members of the community volunteer in the maintenance of the school. The primary goals are to:

produce and maintain fluent Mohawk speakers; instill responsibility, independence, and a positive self-concept; foster respect for Elders and the knowledge they possess; develop pride in and understanding and practice of Haudenosaunee customs and values; ensure the continuation of Haudenosaunee Seven Generations philosophy (all decisions must be considered in light of the consequences for the future seven generations); develop the skills required to function effectively in the over culture Western society. (White, 2015, p. 97-98).

There is a sense of hope now that a system of schooling designed to colonize, displace, and erase the myriad cultures and languages born from the world of the Americas has begun to be dismantled in a concentrated effort towards decolonization. Moreover, modern-day public schools and teachers are beginning to orient themselves toward the collective, social constructivist and community-centered pedagogical paradigm with a focus on experiential, project and problem based curricula, which resemble some aspects of the Indigenous pedagogies that have endured for thousands of years.

Watch and Discuss

A video from Akwesasne TV (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=85xidcNwLQM). This is an overview of the origins, development, and the current Akwesasne Freedom School (AFS). Take note of the pedagogical goals and compare the goals with the goals outlined in Table 4.1.

- What are the goals of the AFS?

- In what ways do the goals of AFS align with one or more of the alternative goals of education?

- In what ways do the goals of AFs counter hegemonic goals?

- What might you, as a future educator, learn from AFS that you can apply to your future classroom?

The Development of Modern American Public Schools

As the 19th century waned, the Protestant work ethic instilled from Puritanism had been internalized in the cultural and political zeitgeist in the Americas for over two and a half centuries. This work ethic indoctrinated individuals to internalize a job-oriented existential worldview, e.g., you are what your job is. Moreover, there were no compulsory education or child labor laws preventing the exploitation of child workers. At this time, the concept of “childhood” was primarily an affordance for affluent children. Adolescence was not even a socially defined sociological or psychological concept. Children and adolescents from working and underclass backgrounds were seen as “small adults” who could take up the risks of more dangerous unskilled labor tasks in factories or mills. Public schools during this time primarily focused on developing children’s basic literacies and numeracies enough for them to effectively join the workforce usually at the end of 8th grade. The original goal of public education for democratic equality began to subside to an orientation for social efficiency. The exploitation of child labor would continue until labor and social activists had enough gravitas to organize and resist the enormous inequities brought on by the industrialization of the Gilded Age–which became the Progressive Era in the early 20th century.

Child Labor Reform and the Development of Public Secondary Schools

Child labor laws and women’s suffrage were two pivotal social justice triumphs that marked the Progressive Era. Both these victories would also create a radical shift in public education in the early 20th century. Because the majority of teachers at this time were women, women’s suffrage gave women more political and social capital. In 1916, four years prior to the 19th Amendment, The American Federation of Teachers was founded by teacher-activist Magaret Haley and educational philosopher John Dewey. Child Labor laws began in earnest at this same time with the Keating-Owen Act of 1916. In deference to capital interests, however, the Supreme Court overruled this act in 1918. It was not until the New Deal in response to the Great Depression that prohibited most child labor outside of agricultural sectors, which up to this day the policy has severely neglected regulations of agribusiness in terms of child labor especially with undocumented child laborers.

With the establishment of land-grant colleges and universities at the tail end of the 19th century combined with child labor laws in the early 20th century, there became an enormous need for secondary schools to transition youth from grammar, or elementary, schools to secondary schools that could prepare them for either employment or for higher education tracks. In the 19th century most secondary schools were private preparatory schools, or “prep schools,” that served adolescents from affluent social classes and would prepare these students for admission into the private, elite schools at that time. Parochial schools also became more prevalent in response to the Protestant-oriented grammar schools’ tacit connection to the King James version of the bible. Bishop John J. Hughes founded an independent Catholic school system after he lost his battle with New York City Board of Education to help subsidize Catholic parochial schools. The Catholic school system in New York City began to employ Irish Catholic women graduating from the normal schools from around New York State.

The birth of the secondary schools stemmed from the trends and policies that began to develop public universities across the United States. As a result, the differing goals of public education begin to compete with one another. Moneyed interests like the Carnegie Foundation also began in earnest to direct policy on public education toward social efficiency (Labaree, 1997a) which tends to favor skills-based tracking of students usually based off of standardized reading and math assessments. The Carnegie Foundation lobbied state and federal agencies for the development of norm-referenced assessments, like the SAT, to filter more “attractive” candidates for entrance into the growing public college and universities. Interestingly, non-profit foundations like the Carnegie Foundation became principal stakeholders in testing companies like Educational Testing Service (ETS) that have created these assessments to act as gatekeepers for access to higher education. This becomes antithetical to social mobility goals because students who get tracked into remedial programs have a difficult time accessing curriculum that can prepare them for post-secondary education.

Despite this trend of gatekeeping access to higher education in the first half of the 20th century, the emergence of progressive education at the end of the 19th century helped counter this trend. Progressive education’s emphasis on learning by doing and collaborative learning projects weaved social efficiency’s hands-on learning for real-world application with democratic equalities more emancipatory focus on educating for successful participation in a democracy and life-long learning. For most of the first half of the 20th century, public schools developed with these two goals as primary goals as the primary policy of public education. In addition to these more explicit political goals of education, schools also functioned as institutions of social reproduction: children from working or under typically would fill the same jobs as their parents or caregivers. Most public education policies at this time were primarily controlled by local and state governments with very limited federal oversight. However, this would change at the conclusion of World War II and the beginning of the Cold War.

Meet the Theorist

David Labaree is Professor Emeritus from Stanford University. He has devoted an extensive amount of his scholarship as an educational historian focusing on public Education in the United States. He is primarily concerned with how economic markets affect democratic education.

LISTEN & DISCUSS

A podcast from SchoolED Conversations about Education (and Everything Else) (SchoolED Conversations interview with Dr. David Labaree (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P0ouMfSZ_tg)). An interview with Educational Historian Dr. David Labaree. Take note of the definition and write examples from your own educational experiences on Dr. Labaree goals for education:

- Social Mobility

- Social Efficiency

- Democratic Equality

After listening, share examples with peers. Try to explain these three goals with peers and provide a concrete example of each goal of education.

The National Defense Education Act and Its Implications on Purposes of Schooling

At the beginning of the Cold War when the Soviet Union launched the satellite Sputnik in October of 1957, the United States felt compelled to act. The National Defense Education Act (NDEA) was signed into law by President Eisnehower the following year. The overall goal of the NDEA was to solve the massive shortage of mathematicians in the United States. The shortage of workers in the science, technology, and math fields highly animated the United States’ effort to compete with the Soviet Union in the space and arms race. In addition to funding science and math, the NDEA created funding for schools to invest in foreign languages other than Latin and Greek, which were prior to the NDEA a seminal part of the Liberal Arts curriculum of secondary schools and colleges. The NDEA would shift the public goals of education toward social efficiency goals at the expense of the other alternative goals of education like democratic equality and social mobility. The consequences of the policies undergirding the NDEA would further student tracking where schools placed students into stratified tracks according to abilities: remedial/vocational tracks, average tracks, and gifted and talented/honors tracks. The stratification of students based on standardized testing would go on to have enormous ramifications in education still being felt today.

Civil Rights, Desegregation, and The Elementary and Secondary Education Act

Brown v. Board of Education is a focal point in other chapters in this book, which only reinforces how this court ruling significantly changed public education in the U.S. Along with the NDEA, the landmark court ruling ended school segregation based on race as unconstitutional and marked an new era of federal legislation and policymaking that significantly shaped public education. After the NDEA and Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights era rose to make systemic changes to promote democratic equality for all. As a part of President Johnson’s War on Poverty led to the Elementary and Secondary Education Act in 1965 (ESEA).

Title I designated federal grants for schools serving low-income families and communities. With this legislation, this is one of the first explicit policies dedicated toward a goal of social mobility. Up until this time, most federal and state educational policies oriented toward more social efficiency and democratic equality goals. Directed funds under Title I were closely regulated to support programs for children in communities with high poverty as well as children with special needs that could not be properly supported by local and state funding. Title I continues as it continues to be reauthorized under each subsequent administration. However, as soon as this legislation was enacted, efforts to deregulate the mandates on who and what the funds must be spent began as American economic policy shifted from a well-regulated free-market with federal oversight toward neoliberal economic policies, which emphasized unregulated markets and privatization of public institutions like public schools.

Like Title I, Titles II-VI focused on specific infrastructural needs schools require in order to develop and maintain high quality education. Title II earmarked federal money for libraries, textbooks, and other media to support instruction. The remaining grants focused funding on educational centers, research and training, as well as funding to support Departments of Education in each state. In 1966, Title VI was amended and became Title VII, which designated specific funding for children with special needs. The following year, the Federal government amended Title VII to include funding to bilingual education programs and Title VII became Title VIII.

In 1972 as a part of ESEA amendments, Title IX became a law. Title IX prohibits discrimination based on sex in any school or educational program including school-sponsored sports. Like Brown v. Education, this law has enormous import not only in educational institutions, but larger cultural institutions like amateur and professional sports. This act gave every young girl opportunities to participate in school-related sports. Girls and young women were no longer relegated to spectators. We can still see the effects of Title IX. The exponential growth of women’s college and professional athletics would not have been possible had it not been for Title IX. Title IX clearly outlines the continuing progress of actualizing democratic equality.

Despite desegregation in the late 1950s, public schools continued to be racially and economically segregated due to white flight to suburbs that were systematically redlined to segregate neighborhoods. Racial and economic segregation is a problem that continues to hinder goals for democratic equality. In order to combat the white flight and involuntary busing of children to create a more diverse student population, the reauthorization of ESEA implemented funding for magnet schools to draw and attract diverse student populations to the magnet program, which had competitive admissions for many magnet schools and specialized curriculum based on gifted and talented programs that were born out of the NDEA policies designed to locate, assess, and recruit “gifted” children for accelerated learning programs. The federal government still funds development and implementation of magnet schools for the purposes of recruiting an economically and racially diverse student population.

The ESEA is the foundation of our current federal educational policy. Since its enactment, Congress need to reauthorize the programs and has been amended many different times under different names, some familiar and some not: Education Consolidation and Improvement Act (ECIA) in 1971, Improving America’s Schools Act (IASA) in 1993, No Child Left Behind (NCLB) of 2001 (this legislation significantly altered Title I funding), and Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) of 2015. With each reauthorization and amendment, there has been a shift in orientation of public education as a public good in terms of democratic equality and social efficiency toward a framing of education as a private, commodified good that some could use as a mechanism for their own social mobility. However, with each amendment, education has been transformed from an unlimited public good into a private good, which becomes codified into law as a limited resource in order to transform education and its system of credentialing (high school diploma, bachelor’s degree, master’s, etc.) as economic commodities with an exchange value that can be bought and sold on an unregulated free market. Education, then, has become more transactional. Close readings of each and every reauthorization and amendment to the original ESEA reveal a hidden curriculum designed to maintain a banking model of education where schools continue to function as primary institutions of social reproduction of the economic classes in the U.S.. There is some social mobility for the lucky few who can navigate the trauma of poverty, the myriad of assessments designed as gatekeeping mechanisms, and the haunting reality of housing and food insecurity. Students who receive financial aid to attend college, university, or other post-secondary educational programs are usually not eligible to receive any other benefits like housing or food assistance. Therefore, for many young people living in poverty, they have to choose between shelter and food or post-secondary education with advanced technical training, which could move them out of poverty without being saddled with enormous student debt that would take decades to pay off.

Neoliberalism and Public Education Policy from the 1980s to Now

In 1983, the National Commission on Excellence in Education submitted a report to the Secretary of Education under President Reagan. Like Brown v. Board of Education and the NDEA. The report infamously titled A Nation at Risk would create an enormous shift in educational policy that would provide the framework for many of the local and national policies from the last 40 years like No Child Left Behind, Race to the Top, and “school choice” initiatives. A Nation at Risk would wrestle with the contradictions inherent in the social efficiency and social mobility goals and shift the inefficiencies of public education onto teachers and students rather than governmental policies that instructed how educational policies and funds should be directed for more democratic equality oriented goals. Beginning in the 1970s under President Nixon, educational funding shifted to block grants, which gave states more autonomy in how the funds for education would be spent and allocated. Block grants began to deregulate educational policy and gave local and state governments enormous power on how funds were to be allocated with limited oversight. Much of the ideological shift toward neoliberalism would leave educational policy and funding to more unregulated free-market policies.

The overall organizational structure of public schools is relatively consistent across the U.S. School systems are top-down organizations that resemble the top-down decision making organizational systems of private corporations. The U.S. The Department of Education oversees federal policies of education like ESEA reauthorizations and congressional amendments to the different Titles I-IX. Each state has a department of education which creates learning standards for all students, oversees credentialing and licensure of teachers and educational specialists, and decides how they will use assessments to measure student and school achievement. There are different organizational structures that govern public schools locally: a district, county, or city/town school boards. This top-down and decision-making structure has not changed since Horace Mann outlined the plan and purpose of the common school era in the 19th century. The political and professional managerial classes are the primary decision makers in the allocation of funds for maintenance and curriculum of schools. Teachers have made inroads in gaining more agency in their own curricular decisions; however, most governance of public schools with some input by practicing educators and teacher unions are made by those in positions of power: superintendents, principals, and elected school boards. Local school boards and superintendents are responsible for allocating funds to support the development and maintenance of each public school.

State funding for public schools differs from each state. Some states dedicate more funds for public schools than others. Additionally, each state uses different revenue sources for funding education in the form of personal or corporate income taxes, sales taxes, “vice” taxes on tobacco and alcohol, and/or lotteries. Most revenue for schools, however, come from local revenue sources–most notable property taxes. There is a large disparity in funding schools. The revenue and tax base of different communities varies widely. Affluent communities can dedicate more resources for schools than more impoverished communities with limited revenue. This description, however, up until now has been more abstract. Context and community shape each school.Geography and relative location to urban centers significantly influence how different locations maintain schools that can meet the needs of each unique community. Rural, urban, and suburban schools have unique affordances and challenges in educating youth..

Rural Education

If one was to walk the halls of a rural school, it might feel like a travel back into the past. Most rural schools were formed from the school consolidation out of the sporadic one-room school houses and common schools at the turn of the 20th century. Most of the school buildings of central schools which house grades K-12 were built at this time. Most rural communities and schools rely on a strong agricultural economic sector. Agriculture and farming have significantly shaped the school calendar, start times, and curriculum of rural schools. Many after-school programs like 4-H and Future Farmers of America, which receive funding from the U.S. The Department of Agriculture developed to help educate and support children growing up in rural areas. The educational goals for rural schools are more overt in terms of social efficiency and social reproduction of its economic base that heavily relies on agriculture and farming, which includes sustenance farming.

Rural schools also operate as cultural hubs and play a key infrastructural role in community planning and organization for rural communities. Because of the central roles rural, public schools play in connecting, maintaining, and sustaining a strong sense of community and solidarity amongst community members, it is of particular importance for robust support for rural schools. Rural schools are more than the sum of its parts and require an analysis of their impact and value beyond a cost-benefit analysis based on profitability and exchange value. Rural schools have a critical, social value that is unique for each community. Rural schools are central in combating brain drain, or capital flight, which occurs when members of the community leave the community for better economic opportunities. Brain drain typically results where rural communities lose skilled professions, e.g., doctors, teachers, engineers, etc, that are critical in maintaining a high quality of life for everyone living in these areas.

Urban Education

Urban schools formed, developed , and grew alongside the growing urban areas that grew out of the industrialization of the 19th century. Urban areas grew into critical hubs for finance and industry until the 1970s. Like the urban areas that surround these schools, urban schools have been in infrastructural decay since the deindustrialization of the 1970s when large sectors of manufacturing moved their base of production overseas for cheaper labor. The major source of tax revenue for urban schools left as well. In addition, the federal block grants that gave individual states more authority to choose how to use federal funds for education allowed state governments to stop adequately funding public schools in urban areas. Rather than prioritizing urban schools, many states chose to divert these funds to prioritize the development of the growing suburbs throughout the 1950s to the turn of the 21st century, which required building a plethora of new elementary, middle, and high schools.

Urban schools still face enormous challenges in finding revenue to maintain their buildings which have been in a state of continual disrepair since the 1970s. Moreover, since the neoliberal turn toward privatization of public schools, urban schools have to face additional challenges in obtaining revenue as charter schools have become more common in urban areas. Charter schools receive public funding at the expense of public schools; however, charter schools are significantly less regulated in terms of curriculum and hiring teachers. Gentrification is another challenge for schools and teachers. The process of gentrification displaces working and low-income families out of their neighborhoods because they can no longer afford to live in these neighborhoods. Despite these enormous challenges, urban schools along with a caring cadre of professional and highly qualified teachers continue to organize in local, urban schools. Urban schools have access to infrastructure that rural schools do not have. Urban areas have already built the infrastructure for public transportation and digital communications–many urban areas support free, public wi-fi. Moreover, urban schools are nestled within vibrant centers of art and culture like museums and performing arts centers.

Suburban Education

Suburban schools are a relatively new phenomenon in the history of American education. The development and maintenance of suburbs require a significant amount of resources like roads, water, sewer, energy. The resources needed to maintain and sustain suburban areas vastly and unsustainably exceed the resources needed to maintain either rural or urban areas. Moreover, since single-family housing is the dominant feature of suburbs, there is not a sufficient population and tax-base to support continual maintenance and development of suburban areas. Tax revenue continues to squeeze suburban communities as different departments like police, fire, and schools compete for decreasing funds due to continuous tax cuts and relief for the wealthy and private corporations since the 1980s. It is clear suburban communities need robust city planning and management in order to sustain these areas socially, economically, and ecologically.

Public schools in suburban areas can draw on the affordances available to rural and urban communities. Schools can be hubs for community organization and support like in rural schools. Suburban schools also benefit from having more modernized infrastructural development like buildings and digital communication technology. Suburban schools also have easier access to cultural and performing arts centers. Suburban schools need professional and caring teachers willing to be active members in these communities to help solve the sustainability issues suburban communities face.

Conclusions and Mapping the Future of Public Education

Equitable public education is an ongoing process. As educators, we cannot rest until all young people regardless of race, ethnicity, economic class, language, and ability have access to high-quality education. The promise of public education needs to foreground goals of democratic equality since democracy does not compete nor negate social efficiency or social mobility goals. More importantly, democratic equality attempts to lessen the harm inflicted by hegemonic goals that force assimilation or erasure. We should maintain a critical stance to their own pedagogical practices and be vigilant at identifying the hidden curriculum involved in our unit and lesson development. We should always be asking ourselves two main questions whenever we design any activity, lesson, or unit: Is this emancipatory for the students, community and myself as an educator? Or is this oppressive for the students, community, or myself as an educator?

Post-Reading Activities and Consolidating Understanding:

- Choose the elementary, middle, or high school you attended. Do historical research on your school. When did it get built? What were the historical rationale for building the school? What types of funding did your school receive? Why? In what ways does your community commit to sustaining the school for future children?

- Attend your local school board meeting. What types of decisions does the board make in terms of funding, hiring and retaining faculty and staff, and curriculum?

Glossary

Assimilation: A sociological concept where people from different ethnic backgrounds adopt traits of the dominant cultural group, e.g., adopting the dominant language, dialect, religion, etc.

Banking Model: A term coined educational theorist Paulo Theory that refers to an educational system that positions students as passive receptacle for teachers to deposit knowledge to be stored for a summative assessment. In this model, students do not have any agency and critical thinking is not valued, but, rather, there is a strong emphasis on rote memorization. Friere offers an example of testing students on what is the capital of France, but there is no exploration on what the concept of what a capital entails in terms of political or economic power.

Block Grant: A federal grant from a larger governmental organization to more local governmental agencies where there is limited governmental oversight in how the aid gets spent. Before the 1970s, schools received federal aid to develop school libraries with up-to-date books. However, during President Nixon’s tenure the Department of Education designated these funds into block grants. As a result, state and local governments diverted aid to libraries to other projects leaving most libraries with out-dated texts and media.

Brain Drain: A type of capital flight or migration of highly trained individuals to another region. This creates a region that does not have enough highly trained individuals to meet the needs of a community. For example, rural areas have a difficult time retaining medical professionals to provide service to the members of the community.

Charter School: A school that receives government funding but can operate with much autonomy from a local school district. Charter schools have autonomy in hiring teachers, who may not need professional licensure, and curriculum.

Common School: A 19th century public school, typically grades 1 through 8 that focuses on basic literacy and math skills, e.g., reading, writing, and arithmetic.

Erasure: A systematic removal of a group of people or aspects of a culture to make it seem the people or culture never existed or exists currently. One example of cultural erasure is most depictions of Indigenous peoples have been romanticized historical narratives, while current narratives ignore Indigenous peoples or act as if they no longer exist in the present.

Gentrification: A socioeconomic process of changing the character of a neighborhood by attracting more affluent residents to the area. The process of gentrification raises the cost of housing, which forces working-class residents with less economic resources to relocate. Many of these residents have been a part of this community for generations.

Hegemony: The systematic maintenance of oppression of a group or groups of people over another for the purposes of exerting dominance–ideologically, socially, politically, or economically.

Land-Grant Colleges and Universities: Federal legislation designating public land for the specific purposes of building public colleges and universities.

Magnet School: A public school that receives direct federal funding to support a school with specialized curriculum that can attract students from diverse geographies in order to have a diverse student population in terms of racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic status. The primary purpose is to support schools dedicated to desegregation.

Meritocracy: A system that rewards advancement based on individual achievement or ability rather than rewarding advancement based on political or economic connections of family and friends.

Neoliberal(ism): A political and economic ideology that advocates for deregulation of the free market. It advocates for privatization of the public commons, like schools or other public infrastructures, because it assumes that privatization is more economically efficient than nationally or locally run public entities.

Normal Schools: Preparatory secondary, or “high” schools to train young adults as teachers in public school in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Norm-Referenced Assessment: A standardized test comparing individual students with other students of the same age or grade.

Occidental: Relating to western or European peoples and cultures.

Political Economy: A term from political science and economics that focuses on studying the interactions of market, or national, economies and their intersections with political systems and government.

Parochial School: A private, religious-based (usually Catholic) school for caregivers who preferred an alternative educational path to public schools. Many private, Catholic schools formed as a counter to public schools’ implicit Protestant-oriented curriculum, e..g, the New England Primer with its overt connections to teaching children how to read and recognize the rhetorical patterns in the King James Bible.

Preparatory Schools: Private, tuition-based boarding schools designed to prepare affluent youth for higher education in elite, private universities.

Progressive Education: A pedagogical theory that emphasizes that the best way to learn is by doing. Progressive educators focus on having students do hands-on projects that mimic real-world applications of content.

Survival Schools: Developed by Indigenous activists from the American Indian Movement in the 1970s as an alternative to public schools and the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs residential schools. These schools formed to help Indigenous children take pride in their cultural heritage, learn their languages, and survive within dominant cultures and ideologies that are disorienting to Indigenous worldviews.

Tracking: A system of using standardized tests as means for sorting students according to low, middle, and high ability groups–usually reading and math assessments. Once students get placed into one of these ability tracks in elementary school it becomes increasingly more difficult for students to move out of these tracks in middle or high school.

Figures

New England Primer is in the Public Domain

Oneonta Normal School Yearbook provided by SUNY Oneonta Milne Library Archives is in the Public Domain

Student Teaching Observation (1902) provided by SUNY Oneonta Milne Library Archives is in the Public Domain

Student Teaching Observation (1902) provided by SUNY Oneonta Milne Library Archives is in the Public Domain

David Labaree by Natalie Frank is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

References

Cordova, V.F. (2007). How it is? The Native American philosophy of V.F. Cordova.The University of Arizona Press.

Janak, E. (2019). A brief history of schooling in the United States: From pre-colonial times to the presents, 1st ed. Palgrave Pivot.

Labaree, D.F. (1997a). How to succeed in school without really learning: The credentials race in American Education. Yale University Press.

Labaree, D. F. (1997b). Public good, private good: The American struggle over educational goals. American Education Research Journal, vol. 34, pp 39-81.

Reyhner, J., & Eder, J. (2017). American Indian education: A history, 2nd ed. The University of Oklahoma Press.

Szaz, M. C. (1999). Education and the American Indian: The road to self-determination since 1928. The University of New Mexico Press.

White, Louellyn (2015). Free to be a Mohawk: Indigenous education at the Akwesasne Freedom School. University of Oklahoma Press.