7 From Slavery to the School to Prison Pipeline: A Call for Restorative Justice

Nicole Waid

Before We Read

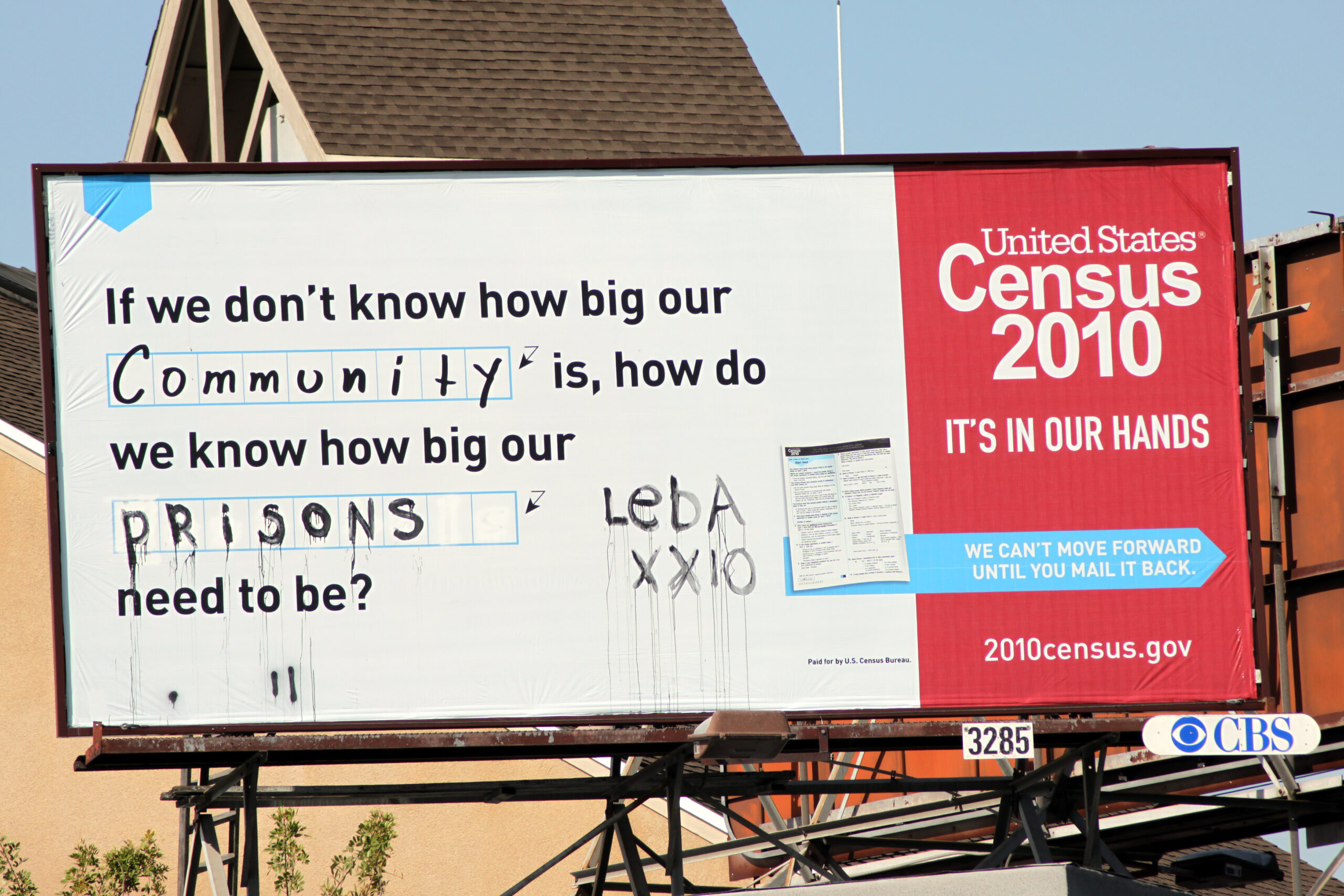

Look at the image below. What message do you think the creator of this image was trying to make? How might the increase in people being sentenced to prison impact schools in disadvantaged communities?

Critical Question for Consideration

As you read, consider these essential questions:

- How have centuries of systemic oppression, from the era of slavery to modern-day institutionalized discrimination, shaped the trajectory of education for marginalized communities in the United States?

-

The United States’ education system has been scarred by historic inequities, tracing back to the era of slavery and persisting through various forms to the present day, best exemplified by the school-to-prison pipeline. From the establishment of segregated schools during the Jim Crow era to present-day disparities in school funding and disciplinary practices, marginalized communities have historically faced systemic barriers to educational opportunities. Many critical theorists like Gloria Ladson- Billings and Kimberle Crenshaw argue that these inequities are deeply rooted in historical injustices, such as the denial of education to enslaved African Americans and the establishment of separate and unequal schooling systems. This introduction sets the stage for an exploration of the multiple issues underlying educational inequality in the United States, underscoring the importance of understanding historical contexts and their enduring impacts on educational outcomes today (Anderson, 2017; Alexander, 2012; Krenshaw 2015).

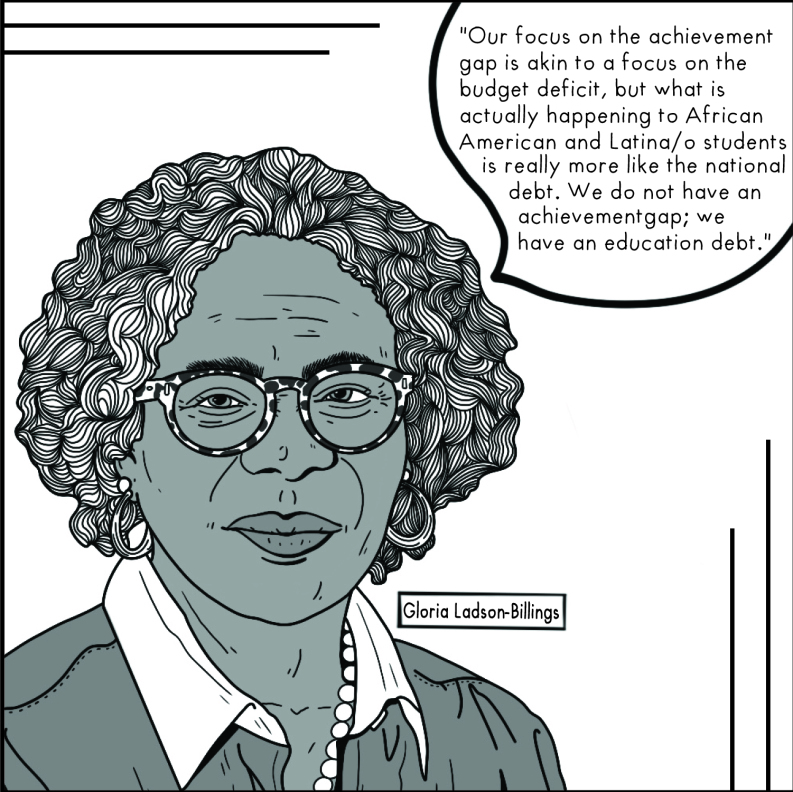

This chapter is rooted in the work of Kimberle Crenshaw’s critical race theory (1989) and Gloria Ladson- Billings’s (1995) culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP). Critical Race Theory (CRT), as described by Kimberlé Crenshaw and other legal scholars, is a framework that examines the ways in which race intersects with systems of power and privilege, particularly within the context of law and society. CRT emphasizes the structural and institutional nature of racism, highlighting how it is embedded within societal norms, laws, and practices. Central to CRT is the recognition that racism operates not only on an individual level but also at the systemic level, perpetuating inequality, and injustice. CRT emphasizes the importance of understanding how race intersects with other social categories, such as gender, class, and sexuality, to produce unique forms of oppression and marginalization. Overall, CRT seeks to challenge dominant narratives, reveal hidden power dynamics, and advocate for social justice and equity (Krenshaw, 1989; Delgado & Stefancic, 2017).

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP), as defined by Gloria Ladson-Billings, is an approach to teaching and learning that acknowledges and embraces students’ cultural backgrounds, identities, and experiences. Ladson-Billings emphasizes the importance of incorporating students’ cultural references, values, and norms into the curriculum and instructional practices to make learning more relevant and engaging for diverse learners. By centering students’ cultural identities and perspectives, CRP aims to foster a sense of belonging, empowerment, and academic success among marginalized and minoritized students (Ladson-Billings, 1995; Gay, 2018). Ladson-Billings has been a longtime advocate for social justice and has described a more just system of discipline called restorative justice where student discipline problems are addressed within the classroom in a way that is responsive to the classroom culture (Ladson-Billings, 2015).

MEET THE THEORIST

Gloria Ladson-Billings (1947- ) is an American pedagogical theorist and teacher educator known for her work in the fields of culturally relevant pedagogy and critical race theory, and the pernicious effects of systemic racism and economic inequality on educational opportunities. Her book The Dreamkeepers: Successful Teachers of African-American Children is a significant text in the field of education. Ladson-Billings is Professor Emerita and formerly the Kellner Family Distinguished Professor of Urban Education in the Department of Curriculum and Instruction at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Thirteenth Amendment

Section 1

Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Defining Freedom (youtube.com)

How does the exception clause of the 13th Amendment, which abolishes slavery ‘except as a punishment for crime,’ intersect with modern incarceration practices, and what are the social, economic, and racial implications of this intersection?

History of Incarceration of Diverse Populations in the United States

The history of law enforcement in the United States is linked to the history of slavery and colonialism in early American history. Since the emergence of policing in the modern era, law enforcement measures have characterized people of color and other marginalized populations as “the other” and established a racial hierarchical social order across the United States. Slaves gained emancipation when the thirteenth amendment to the Constitution of the United States abolished slavery. After Reconstruction policymakers undermined the constitutional extension of equality to black citizens and enacted new laws known as the Black Codes to regulate people of color and other peoples (Hinton & Cook, 2019). A quarter of freedman attended schools set up by the Freedman’s Bureau in 1870. Freedman were people who gained their freedom from the 13th Amendment (Teaching Democracy, Nd.)

The schools in the Jim Crow era were inferior to the school districts white people attended. Southern schools were racially segregated because laws were enacted to ensure students attended different schools. The separate school systems were not equal. Schools for white children received more public money. Black students were often not sent to school because they were needed for farm work, and it was common for black students to only go to school for fourth grade well into the 1900’s. Jim Crow laws were any state or local laws that enforced or legalized racial segregation. Jim Crow laws lasted for almost a century, from the post-Civil War era until around 1968, and their main purpose was to legalize separate but equal public facilities after the Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896.

Congress established the Freedmen’s Bureau in 1865 to aid formally enslaved African Americans and impoverished whites in the South during the Reconstruction era. The bureau played a crucial role in providing education to freed slaves through the establishment of schools. The Freedmen’s Bureau established several schools throughout the Southern states, providing education to thousands of formerly enslaved individuals. While specific statistics vary by source and region, historical records indicate that by the end of its operations, the bureau had established hundreds of schools and employed thousands of teachers, both black and white, to educate freedmen and their children. For example, according to a report by the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (1872) by 1870, the Freedmen’s Bureau had established over 4,000 schools, educating approximately 250,000 students across the Southern states. These schools provided basic education, vocational training, and other essential skills necessary for the economic and social advancement of freemen (Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, 1872).

The following is an excerpt from a January 1866 Freedmen’s Bureau report on education for freed people in the South, written by Freedmen’s Bureau inspector John W. Alvord.

Not only are individuals seen at study, and under the most untoward circumstances, but in very many places I have found what I will call “native schools,” often rude and very imperfect, but there they are, a group of all ages, trying to learn. Some young man, some woman, or old preacher, in cellar, or shed, or corner of a negro meetinghouse, with the alphabet in hand, or a torn spelling-book, is their teacher. All are full of enthusiasm with the new knowledge The Book is imparting to them . . .

A still higher order of this native teaching is seen in the colored schools at Charleston, Savannah, and New Orleans. With many disadvantages, they bear a very good examination. One I visited in the latter city, of 300 pupils, and taught by educated colored men, would bear comparison with any ordinary school at the north. Not only good reading and spelling were heard, but lessons at the black board in arithmetic, recitations in geography and English grammar. Very creditable specimens of writing were shown, and all the older classes could read or recite as fluently in French as in English. This was a free school, supported by the colored people of the city. . . All the above cases illustrate the remark that this educational movement among the freedmen has in it a self-sustaining element. I took special pains to ascertain the facts on this particular point, and have to report that there are schools of this kind in some stage of advancement (taught and supported wholly by the people themselves) in all the large places I visited—often numbers of them, and they are also making their appearance through the interior of the entire country. The superintendent of South Carolina assured me that there was not a place of any size in the whole of that State where such a school was not attempted. I have much testimony, both oral and written, from others well informed, that the same is true of other States. There can scarcely be a doubt, and I venture the estimate, that at least 500 schools of this description are already in operation throughout the south. If, therefore, all these be added, and including soldiers and individuals at study, we shall have at least 125,000 as the entire educational census of these lately emancipated people.

This is a wonderful state of affairs. We have just emerged from a terrific war; peace is not yet declared. There is scarcely the beginning of reorganized society at the south; and yet here are a people long imbruted by slavery, and the most despised of any on earth, whose chains are no sooner broken than they spring to their feet and start up an exceeding great army, clothing themselves with intelligence. What other people on earth have ever shown, while in their ignorance, such a passion for education? (Facing History & Ourselves,n.d.)

Question to Consider

What does the passage suggest about the educational movement among the freedmen?

The Great Migration and the Great Depression

Between 1900 and 1970, approximately 6 million black people migrated from the South to the North. Jim Crow laws in the South reduced employment opportunities, which prompted waves of black men North in search of better opportunities. In the 1st wave of the Great Migration, about 1.5 million Black migrants moved between 1910 and 1940 (Baran, Chyn & Stewart, 2023). Research suggests that moving to the North brought more opportunities for black people, but there was also a higher probability of incarceration (Eriksson, 2019).

The Great Depression

The Great Depression, which began in 1929 and persisted throughout the 1930s, was one of the most significant crises in the history of the United States. The Great Depression had a profound impact on all aspects of American society, including education. During the Great Depression, black people experienced disproportionately elevated levels of unemployment compared to the general population. While official government statistics on unemployment rates specific to African Americans during the Great Depression may not be as comprehensive as contemporary data, historical accounts and studies provide insights into the extent of unemployment among African Americans during that period. According to Wilson (2009), African American unemployment rates during the Great Depression often exceeded those of white Americans. Some estimates suggest that African American unemployment rates reached as high as 50% or even more in some urban areas heavily affected by economic downturns, such as Harlem in New York City and the South Side of Chicago. These high unemployment rates among African Americans during the Great Depression were greatly impacted by discriminatory hiring practices, unequal access to relief programs, and systemic racism prevalent in the workforce and society at the time. African Americans faced significant barriers to employment, including racial segregation, lower wages for the same work as white Americans, and limited opportunities for advancement (Wilson, 2009).

There were many racial disparities in the criminal justice system in the 1930’s. According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, by 1939, the incarceration rate reached 137 people incarcerated per 100,000. This incarceration level was not obtained in the United States for the next 41 years (US Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, n.d.). In 1930, the white-black disparity in incarceration rates was 4.1 times higher for blacks than whites (Wagner, October 7, 2001).

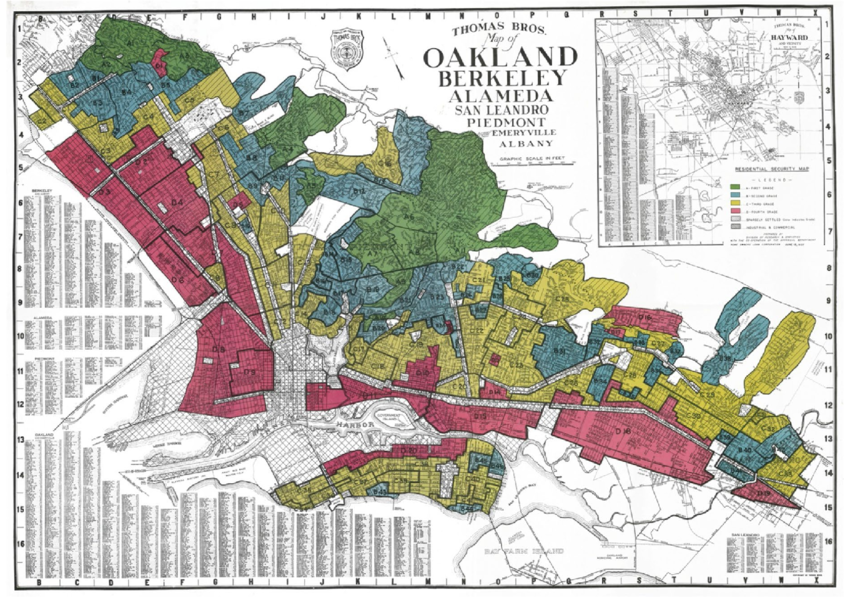

The discriminatory practice of redlining emerged during the Great Depression, leading to several negative consequences. Redlining is a practice where the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) assigned A-D security ratings to neighborhoods across the United States between 1935 and 1940. HOLC maps have had lingering adverse effects on modern outcomes such as credit scores, family structure, home values, household income, neighborhood segregation, and incarceration (Aaronson et al. 2020). Redlining also impacted other important neighborhood features, like education and a healthy environment. Businesses were less inclined to do business in redlined areas because they were deemed hazardous, meaning residents often had to travel outside their communities for things like groceries (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, 2022).

When HOLC was created in 1935 and worked with the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) to ensure loans under New Deal legislation. The HOLC would deem black communities a hazard leading to denial of home loans, and housing covenants excluded black people from buying homes in their neighborhoods. Lukes and Cleveland (2024) examined school funding disparities that have occurred and reached the conclusion that schools and districts located today in historically redlined D neighborhoods have less per-pupil revenues, larger shares of Black and non-White student populations, and worse average test scores relative to those located in A, B, and C neighborhoods. These findings suggest that policymakers need to consider the historical implications of redlining and past neighborhood inequality on neighborhoods today when designing modern interventions focused on improving the life outcomes of students of color and students from low-socioeconomic backgrounds.

Grant (1993) presented educational statistics to highlight the number of students aged 5-20 from 1850-1955 who were enrolled in schools. The statistics show that over time the number of black students enrolled in schools increased dramatically in the period 1850-1955. Due to the Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896, schools were legally segregated in “separate but equal” conditions.

Spotlight on Albany’s Historic Problem with Redlining and its Impact on Schools

In 1938, Albany, New York the HOLC map was created. During this time,here was an influx of black Americans moving north to get more opportunities during the Great Migration. The map designated four sections of the city as rated-D zones. These zones were occupied by Black communtities, with some foreign-born immigrants also residing in the area. Jasmine Higgins’ ancestors moved to Albany during the Great Migration from the South while the Black population doubling every year from 1950 to 1980 (Mikati & Medina, June 6, 2021). According to Mikati and Medina, while one-third of Albany identifies as Black, they are mostly condensed into three neighborhoods located in the heart of Albany; Arbor Hill, West Hill, and South End had been redlined in 1938. Albany’s racial inequities closely reflect the 1938 map. Only 20% of Black residents from Albany are homeowners with an overall poverty rate is 22% compared to 10.5%nationally. According to Silberstein (December 27, 2019), students of color, immigrant students, and those from single-parent households have historically concentrated in underfunded, declining neighborhoods, resulting in fewer opportunities for many socioeconomic factors like good schools. Silberstein noted that according to researchers at Brandeis University, Arbor Hill ranks amongst the lowest opportunity areas for children. Using 2015 census data from neighborhoods around the country and compared the level of opportunities such as graduation rates, percentage of immigrant and single-parent households, income, and the availability of stable housing and green spaces to produce a “Child Opportunity Index.” These areas were rated from 1 to 100, with the highest numbers for places with the most opportunity. Arbor Hill ranked an opportunity score of 1 in the study.

Looking at present-day Albany, an observer can see the lasting impact of redlining in today’s schools. Albany school discipline records paint an alarming portrait of the racial divide in school suspensions. According to the Center for Civil Rights Remedies (2015), Albany suspended 44% of Black male secondary students with disabilities at least once in 2011-12. All Black male secondary students face a high suspension risk of 40%.

The nationwide systemic impact of redlining on schools has left enduring disparities in educational opportunities and outcomes (Massey & Denton, 1993). Redlining, a discriminatory practice in the mid-20th century, systematically denied services, including quality education, to neighborhoods based on their racial or ethnic composition (Rothstein, 2017). During the Great Depression, Franklin D. Roosevelt proposed the New Deal which was a series of new programs that were proposed to provide relief, recovery, and reform to both the government and the American people. One program that was initiated under the New Deal was the National Industry Recovery Act, which allowed Roosevelt to sign executive orders that would set up industrial cartels that made it illegal to hire people below a minimum wage, which led to approximately 500,000 black people losing their jobs. The New Deal policies made it more difficult to hire new workers, making home ownership out of reach for many Black Americans (Powell, 2003).

According to Brandt (2020) the structure of home mortgages varies from the mortgages we see today. In the 1930’s it was customary to require 50% of the home’s cost as a down payment and forced the homeowner to pay off the remaining balance in monthly installments for a term of 5 to 10 years. To address the fact that approximately 1000 people per day were defaulting on their mortgages the New Deal set up the HOLC and FHA to federally insure mortgages. While this action did invigorate home ownership, the program was set up in an era that did not recognize the civil rights for black people, so the efforts for relief excluded many black people from home ownership (Brandt, 2020).

One of the most significant effects of redlining was the increase of racial segregation in schools (Orfield & Lee, 2007). Schools in redlined neighborhoods attended by marginalized populations often face chronic underfunding. Lukes and Cleaveland (2024) studied the link between HOLC maps and current school funding and found that schools mapped to HOLC D grade areas have the highest shares of students qualifying for free and reduced-price lunch, making them eligible for Title I funding, and have worse school-level average math and reading scores than their more highly rated A, B, and C peers, nationally and regionally. This disparity in funding perpetuated unequal access to quality education, perpetuating cycles of disadvantage and inequality (Renzulli & Evans, 2005).

The legacy of redlining continues to impact educational opportunities for marginalized communities (Frankenberg & Lee, 2002). Generations of students from redlined neighborhoods have experienced barriers to academic achievement and socioeconomic mobility (Reardon & Owens, 2014). Limited access to quality education restricts opportunities for higher education and economic advancement, perpetuating intergenerational cycles of poverty (Hill, 2018).

Efforts to address the systemic impact of redlining on schools necessitate comprehensive strategies aimed at promoting equity and addressing historical injustices (Welner & Carter, 2013). Targeted investments in under-resourced schools, along with policies aimed at addressing segregation and inequality in housing and communities, are essential to promoting educational equity and opportunity for all students (Noguera, 2003).

Brown v. Board of Education at 70: The Problem with Segregated Schools

In the early 1950s, racial segregation in public schools was still widespread in many parts of the United States. Many states in the Jim Crow South were legally segregated under the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson supreme court case. These laws enforced racial segregation in schools, with African American students attending separate schools that were often inferior in terms of funding and quality of education. In May 1954, the Supreme Court overturned Plessy v. Ferguson in the Brown v. Board of Education ruling. The Brown v. Board of Education led to the legal desegregation of schools. This ruling was met with resistance and was followed -up by the 1955 Brown II decision that stated that desegregation must proceed with “all deliberate speed.” Despite the legal rulings, many schools resisted desegregation, most notably in the case of the Little Rock Nine in Little Rock, Arkansas. This incident prompted President Dwight D. Eisenhower to send in the 101st Airborne in and federalized the Arkansas National Guard troops to assist in the desegregation process.

Even with the monumental strides Brown v. Board of Education and Brown II court decisions, schools continue to be segregated for assorted reasons well into the 21st century. According to Pendharkar (June 7, 2023), suggested that school segregation has increased in the past three decades. Pendharkar highlighted a May 2023 report released by the United States Department of Education which stated that research indicated that racially and socioeconomically isolated schools often have less access to the necessary resources and funding needed to ensure that equitable educational opportunities are provided for all students. Metlzer, (May 6, 2024) predicated the notion that there are two main factors driving the increase: the end of most court oversight that required school districts to create integrated schools, and policies that favor school choice and parental preference. According to Metlzer (2024), “between 1991 and 2019, black-white segregation increased by 3.5 percentage points in the 533 districts that serve at least 2,500 Black students, an increase of 25% from historically low levels. But in the 100 largest school districts, which serve about 38% of all Black students, the analysis found segregation increased by 8 percentage points — a 64% increase”. Scholars have argued that achievement gap, a term used to describe differences in educational outcomes between students, can be explained at least in part by differences in opportunity driven by inequitable distribution of resources and funding (Milner, 2013).

Racial isolation in schools has persisted well into the 21st century. According to the enrollment data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) reported in 2022 white students now make up 45% of all students enrolled in public schools. While the overall school population has become more racially and ethnically diverse, some research suggests that divisions among races have increased in the last 30 years (US Department of Education, May 2023). The US Department of Education report on the state of school diversity in the United States highlights that racial inequities are often exacerbated by societal factors such as poverty, opportunity gaps, and inequitable funding. Adverse societal factors often lead to lower-performing schools in urban areas having higher incidences of school disciplinary actions among marginalized communities. Since 1970, these factors have contributed to zero-tolerance policies, which include rigid responses to breaking the rule and resulted in automatic severe penalties, such as suspension or expulsion, sometimes for minor infractions. These policies resulted in an increase in the number of school suspensions and expulsions, particularly among marginalized communities. (US Department of Education, May 2023). Thus, the results have created a constant funnel of students from schools to prisons, or what many label the school-to-prison pipeline.

In 1973, the Supreme Court heard San Antonio v. Rodriguez (Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1, 1973). The case dealt with the issue of school funding. As you watch, ask yourself if you agree with the Supreme Court’s three standards that were set forth in the majority’s decision to make an equal protection claim? Why or why not?

Richard Nixon’s War on Crime and its Impact on Schools

President Richard Nixon’s war on crime, which emerged in the late 1960s, had far-reaching consequences for the United States education system. Nixon’s war on crime was officially announced in 1969 and was a significant shift in federal policy towards criminal justice. The war on crime was driven by concerns about rising crime rates and social unrest present in the late 1960’s in the United States, the initiative aimed to increase law enforcement capabilities, enhance punitive measures, and prioritize the fight against crime as a national priority (President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice, 1967). According to Alexander (2010), the war on crime laid the groundwork for the militarization of school discipline. Federal funds were allocated to hire school resource officers to maintain order within schools. The presence of law enforcement in schools introduced a punitive element that shifted the focus from education to control, contributing to an environment where minor disciplinary infractions were often treated as criminal offenses.

Zero-tolerance policies emerged in schools when the war on crime was instituted. Students, especially those who come from marginalized communities, became part of a cycle where school disciplinary actions became a precursor for involvement in the criminal justice system (Nellis, 2011). This criminalization of students under Nixon’s policies led to a sharp increase in expulsions instead of addressing the root causes of the students’ misbehavior through supportive school environments. This approach perpetuated the school-to-prison pipeline, funneling young individuals from schools into the criminal justice system (Sughrue, 2013).

Ronald Reagan’s War on Drugs and its Impact on the School-to-Prison Pipeline

Reagan’s war on drugs in the 1980’s played a significant role in fueling the school-to-prison pipeline, creating a cycle of youth incarceration that disproportionately affected marginalized communities. The establishment of mandatory minimum sentences, increased school resource officers in schools, and the racial disparities inherent in the policies led to many negative consequences. Alexander (2010) discussed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which established mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses. These punitive measures disproportionately affected marginalized communities, leading to an increase in the incarceration of nonviolent offenders. The implementation of mandatory minimums exacerbated the school-to-prison pipeline by removing youths from the school system and funneling them into the criminal justice system. Reagan’s war on drugs also prompted the expansion of school resource officers in schools which led to a more oppressive school environment. Under zero-tolerance policies even routine disciplinary issues that once were handled within the school transformed into police involvement, funneling students into the juvenile justice system, and setting them on a path towards incarceration (Nellis, 2016).

There has been a growing number of suspensions since 1973 in the United States. In 1973, the overall U.S. suspension rate was 4%. By the 2009–10 school year, suspensions had increased to 7%, with particularly sharp increases from the mid-1980s through the 1990s. (Leung-Gagne, McComb, Scott, C., and Losen, September, 2022). Zero tolerance policies that were in place impacted black students disproportionally higher than their white counterparts.

The 1994 Crime Bill

The 1994 Crime Bill inadvertently accelerated the school-to-prison pipeline by increasing punitive disciplinary measures in schools. The Clinton Administration instituted a three-strikes policy, which mandated life sentences for individuals convicted of a violent felony after two or more prior convictions, promoted and expanded zero-tolerance policies, and increased police presence in schools. Keeping with patterns of school suspensions in previous time periods, The Crime Bill disproportionately impacted marginalized communities, contributing to the overrepresentation of minorities in the criminal justice system. Growing rates of incarceration impacted neighborhoods, causing many social-emotional concerns (Alexander, 2020).

The Unintended Consequences of No Child Left Behind

On January 8, 2002, No Child Left Behind (NCLB) was signed into law. No Child Left Behind placed enormous pressure on administrators to improve student achievement and address disruptive students from schools. The strict guidelines set up by NCLB led to many school districts adopting zero-tolerance policies to address discipline issues that were plaguing schools nationwide. When problems occurred in the classroom mitigating circumstances were not considered and prompted a growing number of schools to adopt discipline plans that included suspensions and expulsions (Klehr, 2009).

There were many actions taken to achieve the harsh standards that were enacted into law under NCLB. The legislation emphasized standardized testing and tied school funding to the performance of student test scores from grades 3-8. Opponents of NCLB felt that the move to standardized testing is that teachers would often narrow the curriculum to teach to the standardized test. Schools that did not meet the Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP) outlined by state and federal law would be labeled a school in need of improvement. School funding was tied to a school’s AYP. Opponents felt that taking funding away from low-performing schools would stigmatize schools and would make meeting the more rigorous standards more difficult.

One of the most controversial elements of NCLB was the movement toward zero-tolerance policies that were punitive in nature. Some of the characteristics of zero-tolerance policies include harsh disciplinary policies, lack of administrative discretion when implementing discipline policies, and it has a negative impact on students (Klehr, 2009).

Every Student Succeeds Act

The Every Student Succeeds Act (Pub. L. No. 114-95, 129 Stat. 1802 (2015) undid some of the more controversial provisions under NCLB. Every Student Succeeds Act emphasizes the importance of promoting safe and supportive school communities. The law encourages the use of evidence-based practices for school discipline and encourages schools to implement positive behavioral interventions and supports (PBIS) to improve student behavior and overall school climate. According to the U.S. Department of Education (2016) civil rights data collection, the school suspensions, and expulsions in K–12 public education displays major racial disparities. African American K–12 students account for 1.1 million of the 2.8 million out-of-school suspensions administered in School Year 2013–14, making African American students 3.8 times more likely to be suspended and 1.9 times more likely to be expelled than their white peers. Title II of ESSA (Every Student Succeeds Act) encourages states to provide support more effective instruction of their teachers with in-service training to identify students in need of intervention and support and help educators how to refer for intervention students who may have been affected by trauma in their communities or who are at risk for mental health issues.

Breaking the School to Prison Pipeline with Restorative Justice

Restorative justice is an approach to school discipline that emphasizes repairing harm through processes that includes all stakeholders in the process. Restorative justice aims to build community and address the root causes of misconduct through practices like circles, conferences, and mediation. The ACLU of Washington (December 9, 2009) advocated for a shift away from zero-tolerance policies in schools established under Richard Nixon, arguing that such approaches disproportionately harm marginalized communities. The ACLU pointed out the negative impacts of zero-tolerance policies on students of color and those with disabilities, leading to higher rates of suspension and expulsion. It highlights the need for a restorative approach to discipline, focusing on understanding the root causes of behavior and addressing them constructively. They called for the implementation of alternative approaches to school discipline such as restorative justice, which prioritizes dialogue and reconciliation over punishment. The ACLU emphasized the importance of community engagement in shaping school policies and encourages a comprehensive approach to student well-being.

According to Payne and Welch (2013), schools with punitive discipline policies are prevalent in schools after decades of the school-to-prison pipeline’s creation and are trying to transition to a community-building approach to discipline. During the latter part of the 20th century, domestic policies took a hardline approach to crime and those punitive policies spilled beyond the schoolhouse doors. Over time, the zero tolerance policies under the Nixon, Reagan, and Clinton administrations have led to many harsh punishments in schools such as suspensions and expulsions. This phenomenon has pulled students out of the classroom and into the criminal justice system. The goal of schools is to educate students; pulling students out of the learning environment and into the criminal justice system makes it impossible to achieve our goal as educators.

The Five Rs of Restorative Justice

There are five Rs that serve as the foundation of restorative justice practices in schools; relationships, respect, responsibility, repair, and reintegration (Title,2007).

Relationships

Relationships lie at the heart of the restorative justice process. The person who caused harm has negatively impacted the lives of members of the school community. Without strong relationships, it becomes increasingly more difficult to create communities that students want to be a part of. As caring classroom teachers, we can attempt to repair these relationships. Once the person who caused harm to the classroom community starts to accept responsibility that leads to the beginning of the restorative process (Title, 2007).

Respect

Every relationship cultivated in the classroom must be nurtured with respect. Teachers must set an expectation for exhibiting and modeling respect for their students. During a restorative practice intervention, all stakeholders must be committed to showing not only respect for others, but also respect for themselves. All members of the restorative process must engage in listening to all perspectives, reserving judgement. Respect in the restorative process helps to make the process less adversarial and more about repairing the relationships that have been damaged because of an infraction in the classroom. When the restorative process is well-defined as being a more proactive approach, classroom discipline takes on a whole different approach that places emphasis on trusting relationships (Title, 2007).

Responsibility

For restorative justice to be an effective process, all stakeholders in the process must address their own responsibility in an infraction. Honesty is paramount when taking responsibility for their actions that cause harm. Even if the harm was unintentional, the person who caused the harm needs to take responsibility for their actions. Deciding to take responsibility is a personal choice and cannot be imposed on someone unwillingly (Title, 2007).

Repair

Once the persons involved have accepted responsibility for their destructive behavior and they have heard in the restorative process about how others were harmed by their action, they are expected to make repairs. Starting the process with the goal of repairing the situation allows us to set aside punitive thoughts of revenge and punishment. It is essential that all stakeholders in the event be involved in identifying the harm and having a voice in how it will be repaired. It is through taking responsibility for one’s own behavior and attempting to make amends that students may regain or strengthen their self-respect and the respect of others (Title, 2007).

Reintegration

To complete the restorative justice process, the stakeholders in the community allow the person who caused harm to accept responsibility for their actions and begin to reintegrate into to the classroom community. Reintegration encourages including all members of the classroom community and the person who caused harm in the restorative process. This process is less harmful than isolating or removing the student. One of the benefits of this stage of the restorative process is that it accentuates the positive things the student brings to the classroom community. Unlike the more punitive outcomes of zero-tolerance policies, restorative justice places an emphasis on what the student who caused harm has learned through the restorative process. By accepting responsibility and agreeing to repair the harm, the student who caused harm rebuilds the trust to be reintegrated into the classroom community (Title, 2007).

Integrating Restorative Justice in Schools: A Case Study Approach

Considering traditional discipline measures failing our students, especially among marginalized groups of students, alternative approaches to zero-tolerance policies of the past have been adopted across the nation. A study of 485 middle schools in California examined schools over a six-year period and noted the outcome and impacts on schools and who had integrated restorative justice principles into their disciplinary practices. The key findings of the study showed that schools that adopted restorative practices have less school suspensions and expulsions. Additionally, schoolwide school discipline and school climate improved because of using restorative practices (Darling-Hammond, 2023). Weaver & Swank (2020) also conducted a case study in the southeastern United States and examined 1000 middle school students, 60% of whom were marginalized students. The findings revealed that stakeholders representing various groups, including administration, instructional staff, and students, reported success in implementing a restorative justice approach to their discipline (Weaver & Swank, 2020).

Jones (June 16, 2022) highlighted Fremont High School in Oakland, California. In 2017, Fremont High School faced high discipline rates, low attendance, frequent fights, and a low graduation rate, with only 1 in 4 graduates qualifying for public college in California and 1 in 3 dropping out. With a newly rebuilt campus and a dedicated effort to enhance a positive school climate, Fremont has experienced a 20% increase in enrollment, contrasting with the districtwide decline. Additionally, the number of students eligible for college admission has tripled. The transformation is attributed to a restorative justice program that was initially aimed at dispute resolution but has since evolved into a comprehensive overhaul of the school’s culture (Johnson, June 16, 2022). Schools like Fremont High School are emblematic of the vision for a more culturally responsive approach to classroom discipline. The research points to addressing restorative practices school-wide, and not in a single classroom. Teachers can model respect and focus on building inclusive environments without fear of punishment.

| Traditional | Situation | Restorative |

| The school security guard breaks it up and the students are sent to the principal’s office for punishment. | Brad is shoved in the hallway and a scene ensues | Students and teachers intervene, de-escalate the situation and a time to meet is scheduled for that day. |

| Brad is suspended for 3 days and will have to serve detention when he returns to school. | Brad learns his fate | Facilitators, Brad, and the other student meet in a restorative justice circle to discuss the fight, come to find it was a misunderstanding and each student agrees to write a letter of apology |

| Brad is not in school, missing valuable learning opportunities and a scheduled session with a tutor. | The next day … | Brad meets with his tutor; gets help on an assignment he has struggled with and is more invested in the restorative school community. |

Benefits of Implementation of Restorative Justice Programs in Schools

Restorative justice practices have grown in popularity and are seen as an effective approach to address disciplinary issues in schools, promoting a positive and inclusive school environment. Unlike traditional zero-tolerance punitive measures, restorative justice focuses on repairing harm, building relationships, and promoting a sense of responsibility. There are many benefits of implementing a restorative justice program. Restorative justice programs contribute to the creation of a positive school climate by emphasizing communication, empathy, and understanding. According to a study by Morrison, Vaandering, and Cunningham (2018), schools that adopt restorative justice experience improved relationships among students and between students and staff, fostering a sense of community. This community building approach focuses on building a culture of respect and limits students causing harm to others.

One of the key advantages of restorative justice in schools is its ability to reduce repeat offenses in the school community. A study by Hopkins and Keene (2016) found that restorative justice practices are associated with lower rates of repeat offenses compared to traditional punitive measures. By addressing the root causes of misbehavior and promoting self-reflection, restorative justice helps students develop a greater sense of responsibility in the community.

Restorative justice practices align with the principles of social and emotional learning, fostering the development of crucial life skills. According to a report by the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL, 2017), restorative justice enhances students’ social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. New York State has implemented the Social Emotional Learning Framework as a guide to assist school leaders on how to promote positive social interactions in the school community.

Social-emotional learning (SEL) encompasses a set of key principles aimed at fostering the development of essential skills and competencies necessary for students’ social, emotional, and academic success. According to CASEL (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning), a leading organization in SEL research and practice, SEL is grounded in five core competencies: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. These competencies serve as the foundation for promoting students’ emotional intelligence, interpersonal skills, and positive behavior. Self-awareness involves recognizing one’s emotions, strengths, and weaknesses, fostering a sense of identity and confidence. Self-management encompasses strategies for regulating emotions, setting goals, and persevering through challenges. Social awareness emphasizes empathy and understanding of others’ perspectives, promoting inclusivity and respect for diversity. Relationship skills focus on effective communication, collaboration, conflict resolution, nurturing healthy interpersonal connections. Responsible decision-making involves considering ethical implications and consequences, making informed choices, and taking responsibility for one’s actions. By integrating SEL principles into educational settings through explicit instruction, supportive environments, and meaningful opportunities for practice, educators can empower students to develop essential life skills that contribute to their overall well-being and success in school and beyond (Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning, 2017).

The process of restorative justice empowers students by involving them in the problem resolution process. Students have a voice in shaping outcomes of an infraction and are afforded the opportunity to take responsibility for their actions. This empowerment fosters a sense of autonomy, as it is shown by Riestenberg and Phelps (2019). This practice attempts to keep students in the classroom rather than writing a discipline referral or removing students from a classroom. Stressing discourse as a way of solving problems in the classroom leads to richer relationships between teachers and their students. Restorative justice practices strengthen the bond between teachers and students. By promoting open communication and understanding, teachers become better equipped to address the underlying causes of disruptive behavior. This can lead to improved teacher-student relationships, as discussed in a study by Thorsborne and Blood (2013).

Barriers to Implementing Restorative Justice in Schools

While restorative justice has gained recognition as a positive alternative to traditional punitive disciplinary measures, there are multiple barriers to the effective implementation of restorative justice in schools nationwide. These barriers can hinder its potential impact on creating a more inclusive and supportive learning environment in the classroom. Considering the domestic policies that were enacted throughout the 20th century, many schools use traditional measures because educators lack proper training in and knowledge of restorative practices (Morrison,2016). Due to the lack of knowledge about how restorative justice works, implementing it in schools is met with great resistance. Because restorative practices are a departure from traditional discipline measures, some administrators meet the implementation of restorative justice with great trepidation (Gregory, Clawson, Davis & Gerewitz, 2016). Without buy-in from administrators and faculty resources, implementing restorative practice may be limited. Limited resources like funding and time to implement restorative practices make it difficult for schools that service students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds.

Take a Stand- Restorative Justice in Schools

You have read about multiple benefits and barriers to implementing restorative justice practices in schools. What are some of these barriers and benefits? After weighing the benefits and barriers do you believe that restorative justice should be implemented in schools or not? Be sure to cite reasons and/or examples to support your position.

Restorative Justice Practices for Schools

When adopting restorative justice practices in schools, there are multiple strategies educators can employ to diffuse situations before they rise to the level of removing a student from the classroom through suspension or expulsion. All restorative practices in schools share a common framing of interactions used to address behaviors in schools;

- All involved parties discuss the incident in question.

- The victim and the accused both are given equal opportunity to speak.

- Teachers act as facilitators, where they ask open-ended questions to promote reflection.

- Questions posed to students often include: What can you do to address this situation? How would you feel if the same thing happened to you? How did your behavior impact your fellow students?

- All involved parties decide on a course of action, and all parties work together to carry out that plan (University of San Diego Professional and Continuing Education, n.d.)

Circles

One of the most popular restorative justice strategies used in schools is the use of circles. Circles involve the whole class and are designed to help the classroom community set their own expectations and standards of behavior for the classroom. During the circle activity, all stakeholders in the classroom participate by sharing their perspectives and the potential causes for misbehavior. By employing the circles strategy, all stakeholders in the classroom are afforded the opportunity to assume a sense of ownership over the rules that shape classroom procedures and rules (University of San Diego Continuing and Professional Education, n.d.).

There are many benefits to using restorative circles in schools. Sherman and Strang (2007) suggested that research shows that schools that use restorative practices like circles experienced declines in disciplinary issues. Through the structured nature of restorative circles students hone their social skills and practice effective communication skills. Restorative circles also require active listening skills to be used by all stakeholders in the classroom. By actively listening to all stakeholders’ perspectives, the class works towards finding the root causes of an infraction. Active listening often leads to increased levels of empathy towards others and better communication skills (Hopkins, 2016). Lastly, restorative circles have the potential to reduce bullying in the classroom. This occurs because when students actively listen to their peers, they start to see the perspectives of others and that might lead to heightened levels of empathy towards others in the classroom community (Smith, 2016).

Learning for Justice, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, created a toolkit to assist educators in developing restorative justice principles to address classroom infractions. According to the toolkit restorative justice practices are inquiry-led and either have the goal of social restoration or self-restoration. Whatever the desired outcome is, the process is driven by a series of questions to examine classroom problems from many perspectives. Open-ended questions such as the following are helpful when addressing problems for the purpose of social restoration:

- Tell me what happened.

- What was your part in what happened?

- What were you thinking at the time?

- How were you feeling at the time?

- Who else was affected by this?

- What have been your thoughts since?

- What are they now?

- How are you feeling now?

- What do you need to do to make things right? Repair the harm that was done? Get past this and move on?

- What can we do to support you?

- What might you do differently when this happens again? (Learning for Justice, n.d.).

Similar open-ended questions are asked when the goal of the restorative circle is self-restoration. Questions such as the following are helpful when conducting a restorative practice for self-restorative purposes:

- Tell me what has been happening.

- What do you think about this situation?

- How are you feeling about this situation?

- How is this getting in the way of your learning? Feeling okay about school? Being the person, you want to be at school?

- What do you need to learn/to do to make things better? Make things right? Reset and get back on track?

- What can we do to support you?

- What might you do differently the next time you find yourself in this situation (Learning for Justice, n.d.)?

Discussion Questions

- How have historical policies and practices like redlining, segregation, and punitive disciplinary measures contributed to the perpetuation of educational inequities for marginalized communities? Provide specific examples from the chapter.

- Evaluate the role of critical race theory (CRT) and culturally responsive pedagogy (CRP) in understanding and addressing systemic racism and inequities in the education system. How can these frameworks inform approaches to creating more equitable learning environments?

- Discuss the implications of the “school-to-prison pipeline” phenomenon. What are the potential long-term consequences for individuals, communities, and society as a whole? How can this cycle be effectively disrupted?

- Analyze the pros and cons of restorative justice practices in educational settings. What are the potential benefits and challenges of implementing these approaches? How can restorative justice be effectively integrated into schools?

- Reflect on the role of educators in promoting social justice and educational equity. What specific strategies or actions can teachers and administrators take to create more inclusive and supportive learning environments for all students, especially those from marginalized backgrounds?

- Examine the intersectionality of race, socioeconomic status, and other factors in shaping educational experiences and outcomes. How can an understanding of intersectionality inform efforts to address disparities and promote equity in education?

- Discuss the role of community engagement and collaboration in fostering positive change in the education system. How can schools, families, and communities work together to dismantle systemic barriers and create more equitable educational opportunities?

Activity

Watch this PBS video.

Inside California Education: Restorative Justice

What restorative strategies did you notice in the video?

Glossary

Achievement Gap: A term used to describe differences in educational outcomes between students.

Adequate Yearly Progress (AYP): Outlined by state and federal law under No Child Left Behind, schools that did not meet certain AYP standards would be labeled a school in need of improvement.

Black Codes: Laws enacted after the Civil War to regulate and restrict the newly freed Black population.

Culturally Responsive Pedagogy (CRP): An approach to teaching and learning that acknowledges and embraces students’ cultural backgrounds, identities, and experiences

Critical Race Theory (CRT): A framework that examines how race intersects with systems of power and privilege, particularly within the context of law and society

Desegregation: The process of ending the segregation of races, especially the separation of Black and white students in public schools as mandated by the Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education ruling in 1954. The ruling declared segregated schools unconstitutional and called for their desegregation.

Freedmen’s Bureau: Established in 1865 to aid formerly enslaved African Americans and impoverished whites in the South during the Reconstruction era, playing a crucial role in providing education to freed slaves.

Great Migration: The movement of over 6 million African Americans from the rural Southern United States to the urban Northeast, Midwest and West between 1910 and 1970, motivated by factors like escaping Jim Crow laws and seeking better economic opportunities.

Jim Crow: State and local laws that enforced racial segregation, primarily in the Southern United States, lasting from the post-Civil War era until around 1968.

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS): An approach encouraged by the Every Student Succeeds Act to improve student behavior and overall school climate.

Redlining: A discriminatory practice where the Homeowners’ Loan Corporation assigned security ratings to neighborhoods, often denying services to areas with significant minority populations.

Restorative Justice: An approach to school discipline that emphasizes repairing harm through processes that include all stakeholders, aiming to build community and address the root causes of misconduct.

School-to-Prison Pipeline: A phenomenon where school disciplinary actions, such as suspensions and expulsions, contribute to funneling students, particularly from marginalized communities, into the criminal justice system.

Segregation: The enforced separation of races, as practiced in the United States between the late 19th century into the 1960s. This included segregated facilities like schools, transportation, restrooms and more under policies like Jim Crow laws, requiring Black people and white people to be separated in most aspects of public life.

Social and Emotional Learning (SEL): A framework that aims to foster the development of essential skills and competencies necessary for students’ social, emotional, and academic success, according to the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL).

Zero-Tolerance Policies: Harsh disciplinary policies in schools that lack administrative discretion and often result in automatic severe penalties, such as suspension or expulsion, for rule violations.

Figures

Census Billboard by Lord Jim is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution License.

Gloria Ladson Billings by Natalie Frank is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution License

“Carte-de-visite of a Freedmen’s School with students and teachers” by John D. Heywood, American is marked with CC0 1.0

HOLC map of Oakland, CA. Published by the Mapping Inequality project [7] under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

References

Aaronson, D., Hartley, D., Mazumder, B. (2020). The effects of the 1930s HOLC “redlining”maps. Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Working Paper.

Alexander, M. (2010). The new Jim Crow: Mass incarceration in the age of colorblindness. The New Press.

Baran, C.; Chyn, E. & Stuart, B.A. (September 2023). The great migration and educational opportunity. Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands. (1872). Retrieved from https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/freedmens-bureau

Carillo, S., Salhotra. P. (July 14, 2022). The U.S. student population is more diverse, but schools are still highly segregated, Retrieved from https://www.npr.org/2022/07/14/1111060299/school-segregation-report.

CASEL. (2017). The positive impact of social and emotional learning for kindergarten to eighth-grade students: Findings from three scientific reviews. Collaborative for Academic, Social,and Emotional Learning.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (Fall,2022). Understanding redlining. Retrieved from Understanding redlining (consumerfinance.gov).

Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1989(1), 139-167.

Darling-Hammond, S. (2023). Fostering belonging, transforming schools: The impact of restorative practices [Brief]. Learning Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/impact-restorative-practices-brief

Davidson, J. (Summer, 2014). Restorative justice. Retrieved from https://www.learningforjustice.org/magazine/summer-2014/restoring-justice.

Dee, T. S., Jacob, B. A., Hoxby, C. M., & Ladd, H. F. (2010). The Impact of No Child Left Behind on Students, Teachers, and Schools [with Comments and Discussion]. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 149–207. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41012846.

Delgado, R., & Stefancic, J. (2017). Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. NYU Press.

Eriksson, K. (2019). Moving North and into jail? The great migration and black incarceration. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 159: 526–538.

Every Student Succeeds Act, Pub. L. No. 114-95, 129 Stat. 1802 (2015).

Facing History & Ourselves, Freedmen’s Bureau Agent Reports on Progress in Education, last updated July 11, 2022.

Federal Reserve History (June 2, 2023) Redlining. Retrieved from https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/redlining.

Fine, Janey, A. (2016). Microcosm of the American public education crisis surrounding race and income (2016). Honors Theses. 147. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/147

Frankenberg, E., & Lee, C. (2002). Brown v. Board of Education: The legacy and challenges of the desegregation of American schools. Journal of Social Issues, 58(2), 235-253.

Gordon, N. (2008). Mapping decline: St. Louis and the American city. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Grant, W.V. (1993). 120 years of American education: A statistical portrait retrieved from 120 Years of American Education: A Statistical Portrait.

Gregory, A., Clawson, K., Davis, A., & Gerewitz, J. (2016). The promise of restorative practices to transform teacher-student relationships and achieve equity in school discipline. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 26(4), 325–353.

Hill, M. L. (2018). School funding, school quality, and student achievement: Evidence from the Rural South. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 37(2), 255-279.

Hinton, E.; Cook, D. (2021). The Mass Criminalization of Black Americans: A historical overview Annual Review of Criminology 2021 4(1), 261-286.

Hochfelder, D. (n.d.) Redlining in Arbor Hill. Retrieved from https://undergroundrailroadhistory.org/redlining-in-albanys-arbor-hill/.

Hopkins, B. L. (2016). Restorative circles: An alternative method for conflict resolution in schools. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 89(3), 83-88.

Hopkins, B., & Keene, T. (2016). Restorative justice in US schools: A research review. Youth & Society, 48(5), 671-697.

Irons, P. (n.d.) Jim Crow Schools retrieved from https://www.aft.org/ae/summer2004/irons.

Klehr, D. (2009). Addressing the unintended consequences of no child left behind and zero tolerance: better strategies for safe schools and successful students. Georgetown Journal on Poverty Law & Policy, 16(Symposium Issue), 585-610.

Learning for Justice. (n.d). Getting started using restorative inquiry. Retrieved from https://www.learningforjustice.org/sites/default/files/2017-08/teaching-tolerance-get-started-using-restorative-inquiry.pdf.

Leung-Gagne, M; McComb J.; Scott, C.; Losen, D.J. (September 2022). Pushed out: Trends and disparities in out-of-school suspension. Retrieved from https://learningpolicyinstitute.org/product/crdc-school-suspension-report.

Losen, D.; Hodson, C.; Keith, M.A. II, Morrison, K. & Belway, S. (2015). District profile: Albany Public Schools, New York. Addendum: Are we closing the school discipline gap? https://civilrightsproject.ucla.edu/resources/projects/center-for-civil-rights-remedies/school-to-prison-folder/federal-reports/are-we-closing-the-school-discipline-gap/district-profiles-ccrr-discipline.pdf.

Lukes, D., & Cleveland, C. (2024). The Lingering legacy of redlining on school funding, diversity, and performance. https://scholar.harvard.edu/chcleveland/publications/lingering-legacy-redlining-school-funding-diversity-and-performance.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Harvard University Press.

Mikati, M.; Medina, E. (June 6, 2021). Times Union. A city divided; How New York’s capital city was splintered along racial lines retrieved from https://www.timesunion.com/projects/2021/albany-divided/.

Milner, H. R. (2013). Rethinking Achievement Gap Talk in Urban Education. Urban Education, 48(1), 3-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085912470417.

Morrison, B. (2016). Restorative justice in education: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 86(1), 127–152.

Morrison, B., Vaandering, D., & Cunningham, C. (2018). Restorative justice in education: What we know so far. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 40(1), 70-91.

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. (July, 2016). Every Student Succeeds Act primer: Reducing incidents of school discipline.

Nellis, A. (2016). The color of justice: Racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons. The Sentencing Project.

Nellis, A. (2011). The school-to-pipeline: Education, discipline, and racialized double standards. In SAGE Handbook of Punishment and Society.

Noguera, P. A. (2003). The trouble with Black boys: The role and influence of environmental and cultural factors on the academic performance of African American males. Urban Education, 38(4), 431-459.

Orfield, G., & Lee, C. (2007). Historic reversals, accelerating resegregation, and the need for new integration strategies. Los Angeles: Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles, University of California.

Phau, A.; Hochfelder, D. (February 16, 2017). Examining the forces and maps that redlined the city of Albany Retrieved from Examining the forces and maps that redlined the city of Albany | All Over Albany.

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

Powell, J. (2003). Why did FDR’s New Deal harm blacks? Cato Institute. Retrieved from Why Did FDR’s New Deal Harm Blacks? | Cato Institute.

President’s Commission on Law Enforcement and Administration of Justice. (1967). The Challenge of Crime in a Free Society. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Public Schools Are Still Segregated. But These Tools Can Help https://www.edweek.org/leadership/public-schools-are-still-segregated-but-these-tools-can-

Reardon, S. F., & Owens, A. (2014). 60 years after Brown: Trends and consequences of school segregation. Annual Review of Sociology, 40, 199-218.

Renzulli, L. A., & Evans, G. W. (2005). Classrooms and corridors: The crisis of legitimacy in desegregated schools. Teachers College Press.

Rodriguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973).

Shelley v. Kraemer. (n.d.). Oyez. https://www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/334us1

Sherman, L. W., & Strang, H. (2007). Restorative justice: The evidence. The Smith Institute.

Silberstein, R. (December 27, 2019.). A tale of 2 cities: NPR highlights stark opportunity gap for children in Albany. Retrieved from https://www.timesunion.com/news/article/A-tale-of-two-cities-NPR-highlights-stark-14934776.php.

Smith, D. C. (2016). School-based restorative justice as an approach for addressing bullying. Journal of School Violence, 15(3), 333-354.

Sughrue, S. A. (2013). The school-to-prison pipeline: A comprehensive assessment. Journal of Law & Education, 42(4), 505-517.

Teach Democracy(n.d.). The Southern “Black Codes” of 1865-1866. Retrieved from https://www.crf-usa.org/brown-v-board-50th-anniversary/southern-black-codes.html.

Thorsborne, M., & Blood, P. (2013). Implementing restorative practices in schools: A practical guide to transforming school communities. Routledge.

Title, B.B. (2007). The five R’s of restorative practice. Retrieved from (coloradocrimevictims.org)

United 4 Social Change. (n.d). San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez (1973): Supreme Court Cases. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=B-2NebSwMpU

University of San Diego Professional and Continuing Education. (n.d.) 6 Restorative justice practices to implement in your classroom [+real examples]. Retrieved from https://pce.sandiego.edu/restorative-justice-in-the-classroom/.

University of San Diego Professional and Continuing Education. (n.d.) Restorative justice 101: Implementing restorative programs & measuring effectiveness. Retrieved from https://pce.sandiego.edu/restorative-justice-101-implementing-restorative-programs-measuring-effectiveness/.

U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Common Core of Data (CCD), “State Nonfiscal Survey of Public Elementary and Secondary Education,” 1995-96 through 2020-21 and 2021-22 Preliminary; and National Elementary and Secondary Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity Projection Model, through 2030.

US Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics (n.d.) Prisoners 1925-1981. retrieved from https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/p2581.pdf

Wagner, P. (October 7, 2001). Racial disparities in the ‘great migration’ to prison.

Weaver, J.L. & Swank, J.M. (2020). A case study of the implementation of restorative justice in a middle school, RMLE Online, 43:4, 1-9, DOI: 10.1080/19404476.2020.1733912.

Wilson, W. J. (2009). African Americans and the Great Depression. Journal of African American History, 94(2), 123-145.