9 A Guiding Compass: Ethics for Educators

Kjersti VanSlyke-Briggs

Before We Read

Below you will see a series of potential issues in ethics. Before reading the chapter, in your opinion, is each bullet below a red flag for educator ethics or not? Partner with a classmate and chat about your assumptions. Return to this list after reading the chapter and reevaluate each prompt.

- A teacher changes the grade on a student’s exam after learning that the student was feeling ill the day of the exam. The teacher added enough points to pass the student on the test.

- A teacher has their own daughter in her class. Another faculty has identified this as a conflict of interest.

- A student has told the teacher that they don’t have a ride home and it is raining. The teacher sees the student walking and stops to pick them up and give them a ride home.

- During a recent snow day, the school administration decided that teachers should instruct digitally using their Google Classroom rather than having just a day off. The science teacher decided that this would be too difficult for his students so he just posted an announcement that they should enjoy the day and they would catch up when they were back in class.

Critical Question for Consideration

As you read, consider this essential question: How can examining the evolution of teacher ethics codes help current and future educators appreciate the complex interplay of perspectives needed to equitably uphold professional responsibilities in an imperfect world?

Teaching is a profession that comes with great responsibility as educators work with students, who happen to be minors, in situations where educators are given great trust by the public. Teachers serve as role models for students in their crucial developmental years and have the ability to profoundly impact their students’ lives, both in positive and negative ways. This is one of the reasons that an educator code of ethics is so important for pre-service teachers to understand before they enter the field. Teacher ethics provide crucial guidance that shapes professional conduct and develops public trust in educators. Understanding the evolution and influence of the codes of ethics implemented across the United States is instrumental for new teachers just entering the field and will not only protect one’s students, but also ensure a productive and safe learning environment while also minimizing the risk of legal complications.

In addition to an ethical code, there is an expectation that educators will engage with students in a manner that will serve as a role model and create a pathway for students to explore their own ethics creation. Educators expose students to new ideas, craft safe classrooms for students to support each other as they grow and learn, and encourage students to respond to each other with kindness and understanding. Caring for one’s students and asking students to care for each other is often viewed as a moral and ethical obligation.

In this chapter, we will explore the importance of professional ethics for educators. First, we will look at some of the earliest forms of a code of ethics and then we will examine some historical events and changes that have led states to develop and adopt codes of ethics for educators. Next, we will explore the common ethical principles highlighted across different codes of ethics. We will examine some research that analyzes the effects ethical standards have had on public k-12 education. Finally, we will examine the societal expectation that educators craft themselves as nurturers of an ethic of care in the classroom and will challenge social assumptions about gendered labor. We will also examine a sample code of ethics and utilize those standards to explore some sample scenarios that could happen in a school.

Ethics or Morals: What’s the Difference

When discussing codes of conduct and values for a profession like teaching, the terms “ethics” and “morals” sometimes get used interchangeably. However, there are subtle differences. Morals typically refer to personal beliefs, teachings, or opinions on what is right and wrong behavior for an individual. They can be informed by upbringing, society, religion, or even culture. Ethics also deal with principles for proper conduct, but focus more narrowly on expectations for a collective professional role rather than individual character overall. Professional ethics provide standards related to duties, practices, and decision-making faced on the job. For teacher ethics, the guidelines center specifically on responsibilities educators have towards students, colleagues, and the integrity of school institutions rather than private life matters outside school settings. This distinction helps frame the purpose and boundaries of what teacher ethics codes aim to address as opposed to broader morality.

The Emergence of Codes of Ethics for Educators

Elements of ethics codes for teachers have existed in some form for over a hundred years although they did not always align with today’s values around equal treatment. In the 1800s through early 1900s, there were extensive restrictions targeting female teachers for anything perceived as less-than-virtuous private behavior. Women often had to agree to not participate in drinking, smoking, gambling or dancing. Even more egregious social policing were bans and punishments for female teachers who chose to marry or get pregnant. In some cases, these rules even extended to extremely specifics rules on behavior. One example from 1872 noted that teachers in an Illinois one-room schoolhouse in Knox County should “spend the remaining time reading the Bible or other good book” after spending ten hours in school; additionally, the teacher coded strictly enforced a policy where “women teachers who marry or engage in unseemly conduct will be dismissed” (Marquardt Blystone, 2014). These rules were expanded and updated in 1915 and reflected no progress in understanding educators as competent adults with full lives outside the classroom. In fact, the updated rules were even more restrictive, noting teachers needed to be “home between the hours of 8 pm and 6 am unless attending a school function.”

The origins of such prohibitions were in upholding what was seen at the time as necessary moral authority to instruct students; however, there is a deep double standard embedded in these rules for women. It essentially crafted, “a two-tiered system of employment in education, one in which women did the bulk of the teaching under the supervision of an increasingly authoritative cadre of male administrators” (Smith, 2022). This is what Tyack referred to as the “pedagogical harem” (1974). The rules were less about setting a standard for ethical behavior as they were about controlling women’s bodies and dictating what was perceived as “moral” in that community. This language itself subtly advances latent judgments on women’s morality rooted in patriarchal, repressed views of female sexuality or duties.

Over time, the teacher ethics landscape has continued to develop and shifted focus away from enforcing traditional morals and disproportionately impacting women, towards upholding the dignity of all persons. This complex history illuminates both how far equitable treatment of teachers as professionals has developed, as well as how recently ethical codes emerged in educational expectations that have aligned with more contemporary ideals. States must continually question normative assumptions and the ever-changing landscape of education as they determine codes of ethics and implement those codes. For instance, with the advent of artificial intelligence tools should the implementation of these codes be considered as teachers utilize those tools to enhance or expedite their own work?

Understanding the development of codes of ethics between the late 1800s and today will assist future educators as they develop their own teaching selves and integrate a strong commitment to ethical practices in their career. While earlier iterations of these codes amounted to little more than a set of rules to abide by, they eventually fell out of fashion as educational landscapes moved beyond one-room schoolhouses and small districts with individual oversight to larger public schools and statewide educational expectations. With more governmental oversight, more modern expectations of educators also evolved. As the teaching profession became more formalized in the late 19th century, there was a growing recognition of the need for standards of professional conduct. The National Education Association (NEA) played a significant role during this time. In 1899, the NEA adopted its first Code of Ethics, outlining principles and standards for teachers’ professional behavior. Since that time, the NEA code has evolved, and the current code was adopted in 1975 by the NEA Representative Assembly.

National Education Association Code of Ethics for Educators

To read the NEA Code of Ethics for Educators visit their website at:

https://www.nea.org/resource-library/code-ethics-educators

These codes are built around two principles: Commitment to the Student and Commitment to the Profession

It is important to examine ethical codes of behavior as separate from one’s values or personal judgments (Strike & Soltis, 2009). While moral judgements or values may inform our day to day interactions, the ethical codes set by the NEA and the individual states are about legal practices and set a standard for educators to follow in their interactions professionally.

Current ethical codes reflect a shift in how the role of a teacher is constructed in society. During the 1960s and the 1970s teachers were viewed as a “neutral chairman” and then this shifted in the 1980s where the educator’s values were viewed as a figure to align with for students (Bergem, 1990, p. 1). This view of educators’ roles has shifted once again in the 2000s and most recently to emphasize each parent’s value system as most important and the teacher as subordinate.

Gendered Expectations and an Ethic of Care

While some ethical behaviors in the classroom are easy to identify (teachers should not strike their students) others are what Krishnamoorthy and Tolbert describe as “mucky” (2022) and less clearly defined. At times, for instance an educator’s ethical commitment to intellectual investigation may introduce texts that are not embraced by close-minded parents. Is this an ethical violation due to the mismatch between familial norms and the diversity, equity and inclusion work educators know is important? To complicate this more, another societal expectation is for teachers to be role models for students. Does this mean to extend to all parts of the educator’s life. For example, should teachers not be seen in establishments that sell alcohol after school while on their own time?

There are not always clear choices to be made and as Krishnamoorthy and Tolbert point out, educator expectations need to “shift away from colonial and masculinist binaries that produce particular moralistic orientations as “right” or “wrong” (2022, p. 1047). Educators often must make ethical decisions in the classroom that shape how students read the world. Selecting the literature students read, particular teaching approaches to apply, and which moments in history to highlight and how such moments will all shape how students read the world and place themselves within it. These choices may be considered ethical considerations as well as political ones. This is what Krishnamoorthy and Tolbert call an “ethical praxis, even a form of conscientization” (2022, p. 1059) and they note that not only is this mucky work, but that it is “dirty, viscous, unclear, not solidified” (2002, p.1059) work. Educators must continue to explore their role in shaping student discourse and introduce novel ideas that they may not have previously explored.

Another ethical practice in schools to consider is the “ethic of care.” As suggested by Colnerud (2006), one discussion emerging during these shifts from early rules setting as ethics and later guiding principles is the “relationship between an ethic of care and ethics based on principles of justice” and the ways “in which benefits and burdens are distributed” (p. 368). Schools are often considered the location where students grow into caring adults and learn not just the content concepts introduced to them, but also ways of being in the world and how to interact with each other. Teachers find that they must, “balance justice and care in their ethical choices and one could say that they are forced to organise care and distribute it justly. Conversely, they must ensure that justice is meted out caringly” (Colnerud, 2006, p. 369).

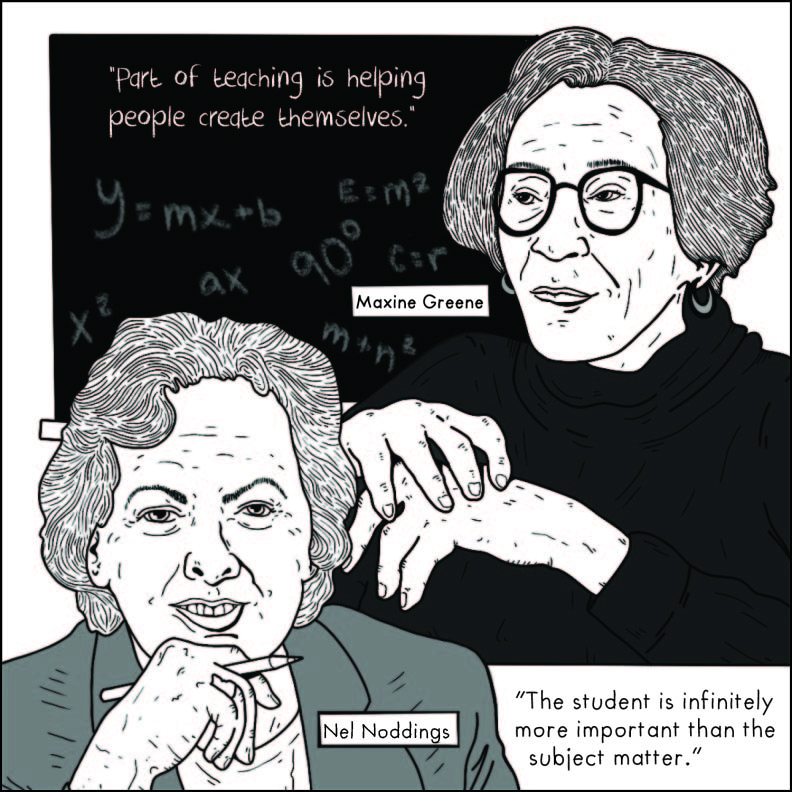

Meet the Theorist

Nel Nodding (1929-2022) was an American educator, scholar, and feminist theorist. She is best known for her work on the ethic of care. She continued to refine her theories late in life and was reflective of her practice. Her text Caring: A Relational Approach to Ethics and Moral Education was originally published in 1984 but was reprinted with updates in 2013.

Researcher, Nel Noddings instructs her readers that this ethic of caring is presented through a relational ethic in that it is “tightly tied to experience because all its deliberations focus on the human beings involved in the situation under consideration and their relations to each other” (1994, p. 173). Noddings also notes that this caring and emotional labor is often characterized as feminine labor. This framework for understanding the role of an educator reinforces long held beliefs that schools should be responsible for the growth of students into contributing and thoughtful members of the citizenry. As Noddings indicates, this work if truly embraced changes how schools function and emphasizes dialog and changes, “almost every aspect of schooling: the current hierarchical structure of management, the rigid mode of allocating time, the kinds of relationships encouraged, the size of schools and classes, the goals of instruction, modes of evaluation, patterns of interaction, selection of content” (1994, p. 175). Noddings concludes her key paper on this topic by noting that society does not really want to solve this problem, “as there is too much at stake, too much to be lost by those already in positions of power” (1994, p.179). The “caring teacher” approach embraced by Noddings (1984), Gilligan (1982), Greene (1995), and Belenky, Clinchy, Goldberger, and Tarule (1986) all support a positionality in which the teacher enacts change through a supportive and nurturing classroom.

Meet the Theorist – Maxine Greene

Maxine Greene (1917-2014) was an American teacher and theorist. She centered much of her work on the gendered work of teaching and the role of women in the field. She also was an advocate and spoke often on the work of the “social imagination” allowing one to imagine a different future to work toward for social justice. She is best known for her work The Dialectic of Freedom (1988).

This early work by theorists to encourage a well-intentioned “ethic of care” and the societal expectation for education to solve all social ills has crafted an untenable situation for educators and in particular one for those educators that embrace a nurturing classroom identity. This is not to say that this should not be a goal of educators, but in recent years educators have been demonized, de-professionalized, and dismissed while also having increased expectations laid at their feet. This is not a new problem. The risk of burnout and personal stress as a result of increased emotional labor by educators that support an ethic of care in their classrooms is high (VanSlyke-Briggs, 2010). In a National Education Association survey conducted in 2022, it found that, “90 percent of members say feeling burned out is a serious problem, with 67 percent saying it’s very serious” (Walker, 2022). Educators must consider mechanisms to prevent their own burnout while also attending to the needs of students and working to establish an ethic of care in their classrooms.

One State’s Approach

In New York State a Code of Ethics for educators was established by the State Standards and Practices Board in June of 2002 and voted into effect by the Board of Regents in July of the same year. This came after a call for an ethics code development in 1998 as part of a teaching reform initiative outlined by The State Board of Regents. The current code was developed in partnership and collaboration with teachers, school administrators, higher education representatives, public members and even a teacher education student as members of a 28 person Standards Board. After a draft of the code was completed, it was reviewed by the Board of Regents and sent out for public comment. The Code of Ethics is comprised of 6 Principles which are designed to include new developments and scenarios in education. This code cannot be used as a basis for discipline by an employer. Instead, there is a different mechanism for that process. This is simply a guidance document to assist teachers in understanding best practices in relation to ethical practices in the classroom.

The New York State Education Department also has guidance on Educator Integrity including The Office of School Personnel Review and Accountability (OSPRA) which investigates allegations concerning the moral character of those who hold New York State teaching certificates. Any person may file a written complaint with the department. This would include those aware of a criminal offense committed by the educator or “an act that raises a reasonable question about the individual’s moral character” (https://www.nysed.gov/educator-integrity/moral-character-actions-part-83). Once a complaint is received, an investigator is assigned to the case.

New York State Educator Code of Ethics

The following six principles can be found at the New York State Education Department website at https://www.highered.nysed.gov/tcert/resteachers/codeofethics.html

Discuss each principle and how it may impact practice.

Principle 1: Educators nurture the intellectual, physical, emotional, social, and civic potential of each student.

Educators promote growth in all students through the integration of intellectual, physical, emotional, social and civic learning. They respect the inherent dignity and worth of each individual. Educators help students to value their own identity, learn more about their cultural heritage, and practice social and civic responsibilities. They help students to reflect on their own learning and connect it to their life experience. They engage students in activities that encourage diverse approaches and solutions to issues, while providing a range of ways for students to demonstrate their abilities and learning. They foster the development of students who can analyze, synthesize, evaluate and communicate information effectively.

Principle 2: Educators create, support, and maintain challenging learning environments for all.

Educators apply their professional knowledge to promote student learning. They know the curriculum and utilize a range of strategies and assessments to address differences. Educators develop and implement programs based upon a strong understanding of human development and learning theory. They support a challenging learning environment. They advocate for necessary resources to teach to higher levels of learning. They establish and maintain clear standards of behavior and civility. Educators are role models, displaying the habits of mind and work necessary to develop and apply knowledge while simultaneously displaying a curiosity and enthusiasm for learning. They invite students to become active, inquisitive, and discerning individuals who reflect upon and monitor their own learning.

Principle 3: Educators commit to their own learning in order to develop their practice.

Educators recognize that professional knowledge and development are the foundations of their practice. They know their subject matter, and they understand how students learn. Educators respect the reciprocal nature of learning between educators and students. They engage in a variety of individual and collaborative learning experiences essential to develop professionally and to promote student learning. They draw on and contribute to various forms of educational research to improve their own practice.

Principle 4: Educators collaborate with colleagues and other professionals in the interest of student learning.

Educators encourage and support their colleagues to build and maintain high standards. They participate in decisions regarding curriculum, instruction and assessment designs, and they share responsibility for the governance of schools. They cooperate with community agencies in using resources and building comprehensive services in support of students. Educators respect fellow professionals and believe that all have the right to teach and learn in a professional and supportive environment. They participate in the preparation and induction of new educators and in professional development for all staff.

Principle 5: Educators collaborate with parents and community, building trust and respecting confidentiality.

Educators partner with parents and other members of the community to enhance school programs and to promote student learning. They also recognize how cultural and linguistic heritage, gender, family and community shape experience and learning. Educators respect the private nature of the special knowledge they have about students and their families and use that knowledge only in the students’ best interests. They advocate for fair opportunity for all children.

Principle 6: Educators advance the intellectual and ethical foundation of the learning community.

Educators recognize the obligations of the trust placed in them. They share the responsibility for understanding what is known, pursuing further knowledge, contributing to the generation of knowledge, and translating knowledge into comprehensible forms. They help students understand that knowledge is often complex and sometimes paradoxical. Educators are confidantes, mentors and advocates for their students’ growth and development. As models for youth and the public, they embody intellectual honesty, diplomacy, tact and fairness.

Discussion Questions

- Why is it important to have ethical standards and guidelines in place for the teaching profession? What purposes do they serve?

- How do ethics differ from morals? Why is this distinction relevant when examining professional ethics and guidelines?

- Past ethics codes sometimes reflected problematic assumptions or disproportionately impacted certain groups. How can we ensure contemporary ethics standards align with ideals of equity and fair treatment? What processes help shape this?

- How might teacher ethics codes need to evolve moving forward to address new issues arising, like the use of artificial intelligence in classrooms? What new considerations might this require?

- How can educators integrate an “ethic of care” within a critical pedagogy framework to address broader societal issues and promote transformative learning experiences for both students and themselves?

Activity

Ethical or Not: Examining Complex Dilemmas through the Lens of Educator Ethics Codes

Before beginning this activity, review the New York State Code of Ethics for Educators. Below are three scenarios that examine potential ethical violations by educators. After reading each scenario, examine it for potential violations of ethics and consider the guiding question posted after each scenario.

Scenario 1

Emily is a 22-year-old student teacher completing her final field experience at Roosevelt Middle School prior to certification. One day, Emily decides to sneak off to the deserted student bathroom during her prep period to take a few puffs from her e-cigarette/vape pen in order to relax. Unbeknownst to her, a recently installed security camera outside the bathroom catches footage of Emily exiting the bathroom. Later that week, the school’s IT administrator detects abnormal levels of vaping residues in tests of the bathroom’s air quality sensors during Emily’s timeframe.

When the principal calls Emily into his office about these issues, she vehemently denies vaping or even owning an e-cigarette. Once presented with both the sensor data and camera footage evidencing otherwise, Emily changes her defense by arguing that “at least she did it secretly where no students could see, so it shouldn’t matter.” Was Emily in violation of any components of the professional code of ethics or laws? Why or why not?

Did Emily violate any aspects of ethical or legal standards for teachers based on this scenario. Make sure to cite specific sections and language from the ethics codes in justifying your arguments. Your response should demonstrate a thoughtful application of the standards to Emily’s concerning behaviors and statements.

Scenario 2

Mark is an 8th grade math teacher who through social media befriends Luis, a quiet student new to his school this year. Luis has few friends and seems to struggle with anxiety in Mark’s class. Wanting to support him, Mark messages Luis on weekends to see how he’s coping, reminds him of class material, and encourages him to join a school dance. While Mark aims to mentor Luis for his benefit, the frequency and familiar tone of the off-hours communications increasingly makes Luis uncomfortable. However, Luis is hesitant to report their interactions or confront a teacher.

One day, a counselor notices Luis’ change in behavior and reaches out to see if anything is wrong. Reluctantly, Luis shows her some messages where Mark appears overly invested in his personal issues unrelated to course studies. The counselor finds this concerning and speaks to the principal regarding whether Mark may have crossed internal communication policies or professional ethical boundaries, even though aiming to help Luis.

Did elements of Mark’s efforts to support his student potentially violate any components of the Code of Ethics? Why or why not? Analyze Mark’s behavior and statements in relation to appropriate educator and student boundaries. Make sure to cite language from the ethics standards in justifying your arguments.

Scenario 3

As online lesson material repositories grew, middle school science teacher Kayla subscribed to several sites offering AI-generated lesson plans aligned to state standards. With 120 students across five periods, manually planning engaging projects every day was challenging. Kayla began assigning the AI-crafted lesson plans after quickly reviewing and approving their quality first. Students were responding well. However, some colleagues felt fully delegating fundamentals like lesson objectives, essential questions and formative assessments violated principles on diligently upholding duties vital to the learning process.

During a district EdTech conference session discussing AI ethics, sharp divisions emerged even among technology staff and administrators. Some argued AI supports teachers in accessing shared best practices by automating routine design tasks. They said just as with teacher toolkits from textbook ancillary materials, the core interaction of creatively guiding activities still comes from Kayla. However, others contended relying on AI algorithms threatened teacher development of contextualized curriculum attuned to students’ needs. Debates ensued around whether AI lesson aids should constitute unethical outsourcing of basic teaching competencies – or if emerging assistive technologies will necessitate updating professional standards for modern times.

Is Kayla’s use of AI to facilitate lesson planning in conflict with any components of the Code of Ethics? Why or why not? Relate principles in the Code to this case around responsible use of resources and diligently upholding duties vital to student development.

Glossary

Code of Ethics: A set of principles and standards that outline the professional responsibilities and conduct expected of individuals within a particular profession. In the context of education, a teacher’s code of ethics outlines the expectations for ethical behavior and decision-making.

Conflict of Interest: A situation in which a person’s personal interests or relationships may potentially influence their professional judgment or actions in a way that could compromise their integrity or impartiality. In education, conflict of interest situations should be avoided to maintain professional ethics.

Critical Pedagogy: An approach to education that emphasizes the development of critical thinking skills, social justice, and equity. Critical pedagogy encourages students to question and challenge societal norms and structures.

Ethic of Care: An ethical framework that emphasizes the importance of relationships, empathy, and compassion in moral decision-making. In the context of education, an ethic of care highlights the educator’s role in nurturing students’ well-being and supporting their holistic development.

Integrity: Being honest and demonstrating strong moral principles.

Moral Character: Qualities like honesty and integrity that reflect one’s ethical values.

NEA: National Education Association, a professional organization for educators in the United States

OSPRA: Office of School Personnel Review and Accountability, investigates educator misconduct in New York

Pedagogy: The theory and practice of teaching, including the methods and strategies used to deliver instruction and facilitate learning. Pedagogy encompasses the educator’s role in designing learning experiences and supporting student development.

Praxis: The process of applying theoretical knowledge or concepts into practical action or application. In education, praxis involves the integration of theory and practice in teaching and learning, emphasizing the transformative nature of education.

Principles: Core values that guide ethical decision-making.

Figures

Nodding and Greene by Natalie Frank is licensed with a Creative Commons Attribution License

References

Bergem, T. (1990). The teacher as moral agent. Journal of Moral Education, 19(2), 88. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724900190203

Belenky, M. F., Clinchy, B. M., Goldberger, N. R., & Tarule, J. M. (1986). Women’s ways of knowing: The development of self, voice, and mind. Basic Books.

Colnerud, G. (2006). Teacher ethics as a research problem: syntheses achieved and new issues. Teachers and Teaching, Theory and Practice, 12(3), 365–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/13450600500467704

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.

Greene, M. (1995). Releasing the imagination: essays on education, the arts, and social change. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Krishnamoorthy, R., & Tolbert, S. (2022). On the muckiness of science, ethics, and preservice teacher education: contemplating the (im)possibilities of a ‘right’-eous stance. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 17(4), 1047–1061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-022-10132-5

Marquardt Blystone, S. (2014). Rules for one-room schoolhouse teachers. Illinois State University. https://news.illinoisstate.edu/2014/02/rules-one-room-schoolhouse-teachers/

Noddings, N. (1984). Caring, a feminine approach to ethics & moral education. University of California Press.

Noddings, N. (1994). An ethic of caring and its implications for instructional arrangements. In L. Stone (Ed.). The Education Feminism Reader (pp. 171-183). Routledge.

Owens, L. Ennis, C. (2005). The ethic of care in teaching: An overview of supportive literature. Quest. National Association of Kinesiology and Physical Education. 57, 392-425.

Smith, K. (2022). Teaching in the light of women’s history. Facing History & Ourselves. https://www.facinghistory.org/ideas-week/teaching-light-womens-history

Strike, K. and Soltis, J. (2009). The ethics of teaching. Teachers College.

Tyack, D. (1974). The one best system: A history of American urban education. Harvard University Press.

VanSlyke-Briggs, K. (2010). The nurturing teacher: Managing the stress of caring. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Walker, T. (2022). Survey: Alarming number of educators may soon leave the profession. NEA Today. National Education Association.