6 Linguistic Diversity in U.S. Education

Maria Cristina Montoya

Before We Read

Before reading, think and share on the following questions:

- Were you encouraged to learn a second language while growing up?

- Do you recognize a heritage language that existed in your family background? Does anyone from your family still speak it? If not, why do you think that it was lost?

- Did you or any of your classmates bring a heritage language to the classroom? Were they encouraged to maintain it or judged?

Critical Question For Consideration

As you read, consider these essential questions: In what ways can teachers collaborate and foster cross-cultural competencies to connect students’ linguistic and cultural funds of knowledge?

A Teacher Story: Discovering Spanish Heritage Linguistic and Cultural Diversity Through Sociolinguistic Pedagogy

In my own experience as a multilingual student and educator, I have been intrigued in discovering both the teaching about and learning the processes of how students who eventually become bilingual or multilingual. Early in my career, I was assigned to teach a Spanish class for heritage speakers before I knew who they were. At that time in the fall of 2000, the only insight that was given to me by a traditional, soon-to-be-retired scholar was: “they do not know their grammar; nor can they write fluently in either language; they mix the languages uncontrollably”. New into the teaching of my own native language, without any experience teaching in bilingual classrooms, I prepared a syllabus with a grammatical focus and very advanced readings; within two weeks of teaching, I was forced to re-do my syllabus, change readings, add movies and songs, and plan lessons that have students investigate variations of Spanish language and culture. During this time, I found myself learning to understand my students, their particularities growing up bilingual/bicultural, and their needs and challenges. Now more than two decades have passed, I have come to develop a critical, sociolinguistic pedagogical approach to encourage student confidence and improvement of their private language; and then, the students turn it towards a public reinforcement of their linguistic identity.

Through this revelatory process, I learned first what not to do. Afterwards, I began to figure out how I should teach these first-and-second-generation Hispanic students coming to my class with specific needs while maintaining their parents’ language and using it in their future professions. My current courses consist of guiding students in a self-discovery process of their biculturalism and bilingualism. Students love to talk about their home routines, their parents’ beliefs, family celebrations, food they eat and music they dance to; so, I make them talk and then write about their own private, family customs. Students re-discover themselves and their parents’ migration struggles through a language that used to be passive and private. I leave the grammatical explicit explanations for last and discuss mechanics of language as they arise from their own fluent writings. Initially, students’ essays are full of oral discourses that they re-write using monolingual dictionaries for the first time and analyzing syllables’ stresses as a game with words and sounds. I avoid using negative judgments about their Spanish and when they say “Yo hablo un español malo” (I speak bad Spanish), I ask them to elaborate on their own appreciation of their language. The pedagogical approach is to use their fluency first and then transform it into a standard use of the Spanish language which they can use publicly, professionally, and proudly.

Some students come to me for the first time with enormous linguistic insecurities, others express that they know Spanish well since they only speak Spanish at home, and their only need is to learn how to place accent marks, and others find the class by luck browsing for an “easy” elective. The reality is that all find each other in my course and become consciously aware of their Hispanic – American identities. They teach me about diversity within my own culture and language, a knowledge that I could have never learned from my graduate courses, but from the direct contact with Spanish heritage speakers in the classroom. Every semester is different; each group brings a new discussion and revelation of the Hispanic heritage culture in the United States, and students end up learning more than accent marks, spelling and verb conjugations. Two decades later, I have learned how to teach Spanish to heritage students by observing, listening, and asking questions to them. None of my experienced colleagues, professors or books could have taught me better than my own bilingual/ bicultural students in the classroom.

The Challenge of Language Minorities: Linguistic Diversity, Linguistic Ideologies in the U.S and the School Institution

Linguistic Ideology

An ideology consists of collective ideas that reflect social needs and aspirations of an individual within a group, a social class, or a culture. An ideology imparts group norms that develop elaborate cognitive systems rationalizing group behaviors from a set of doctrines or beliefs without individual consciousness. Ideologies are spread among members of a community through covert and overt messages broadcasted through news, popular culture (music, film, television), and political events (local, state-wide, and national) such as local board of education meetings or congressional hearings. A language ideology may develop based on a sentiment of pride of a culture or a nation. For example: “The English only movement” imparts the parallel of “one nation-one language” in terms of unification. This ideology becomes exclusive of others who are not part of the speech community/group in power who speak the dominant language. This language ideology also tends to ignore the many disparate Englishes, variation, and dialects of English that become pathologized as “bad” or “incorrect” because of difference in grammar and pronunciation, e.g., African American Vernacular English and Appalachian English, which are complete, full languages with their own rich grammar and history.

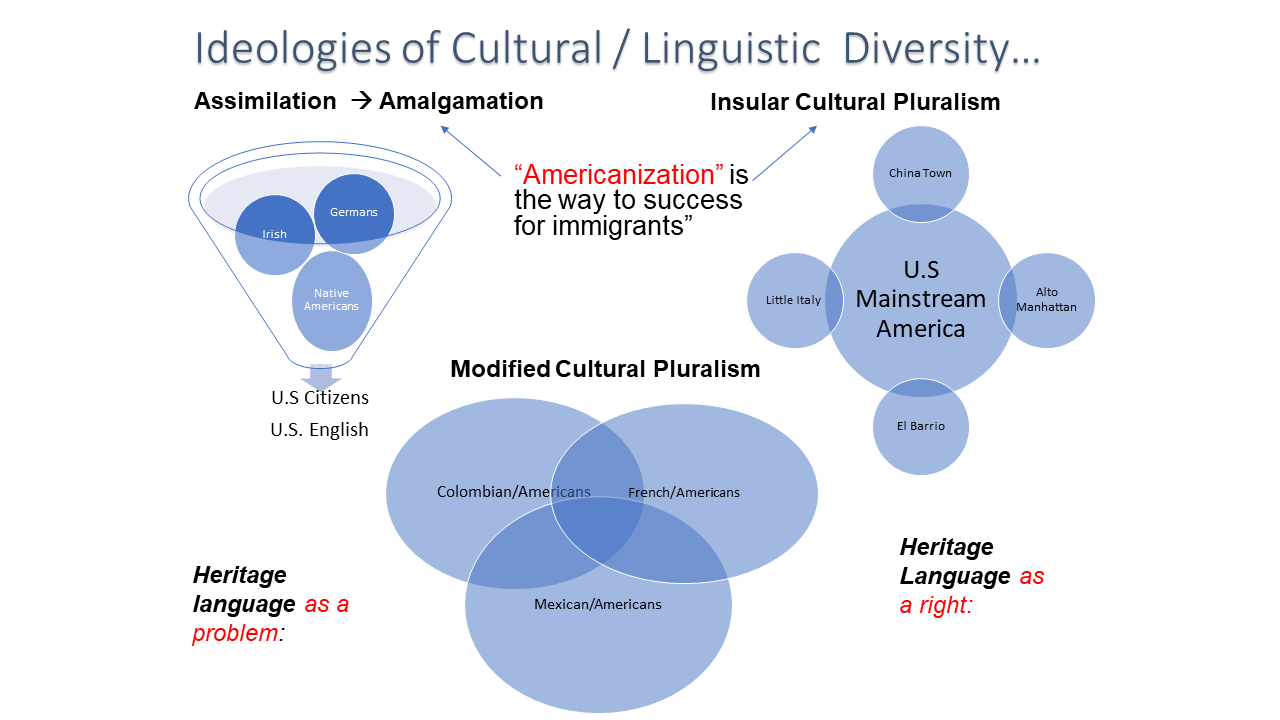

To better understand how a linguistic ideology is formed, first, it is important to differentiate the concepts between Cultural Diversity and Cultural Pluralism. Cultural Diversity is a descriptive concept to say there are different groups in a society with distinctive cultural practices, dialects and languages spoken. There is no judgment associated with the term, and speech communities are diverse in various ways. Cultural Pluralism, on the other hand, is a concept that carries a set of positive values in a diverse setting. In cultural pluralism, diversity is valued, respected, and encouraged. In U.S. history, there have been three types of ideologies shaping human behavior regarding cultural and linguistic diversity: 1.Assimilation/Amalgamation; 2. Insular Cultural Pluralism; and 3. Modified Cultural Pluralism (Reagan, 2009). In the U.S.multiple languages have always been in contact with each other. Linguistic diversity has not increased; it has evolved in response to historical events. Therefore, the change in linguistic diversity is how it has been viewed historically. Those in power making public policy have determined the institutional and societal language used in this nation. English dominated over other European languages in times of colonization and independence; however, language diversity was “inclusive” in constitutional writing and there was never one official language institutionally imposed to the new formed United States of America (Baker, C. & Prys Jones, S.,1998)

Assimilation/Amalgamation

Even during European colonialism, multiple languages co-existed with each other. At this time, Indigenous languages were in contact with the languages of the European colonizers (English, German, French, Dutch, and Spanish). Our Independence period supported multilingualism and bilingual education towards dual maintenance. English was the dominant language in government leadership, “language in power”, and other European languages were embraced as well, yet only for the colonizers’ languages. The same cannot be said about the American Indigenous languages. First Nations peoples, as discussed in an earlier chapter, were subjected to a systematic ethnic cleansing campaign that sought to erase their languages and cultures through forced assimilation in Indian residential and boarding schools.

The second half of the 19th century was a period of great immigration. At this time, there was a growing ethnocentrism amongst the political and social elite encouraging English hegemony. Early stages of the “one language-one nation” ideology emerged, and new immigrants were not encouraged to retain their native languages. If they tried, it was viewed as a lack of assimilation and pride for the new country that was welcoming them and providing opportunities. Children of immigrants were urged to learn English to accomplish the “American Dream”, the heritage language was not necessary for success. This ideology turned, with time, the U.S. into an English monolingual speech community. New generations born of immigrants from multiple backgrounds and languages were becoming monolingual and struggling to understand their new identities. The other two main ideologies, “Insular Cultural Pluralism” and “Modified Cultural Pluralism” do not propose any significant approach to valuing linguistic diversity at the structural level.

Insular Cultural Pluralism

Insular Cultural Pluralism consists of various linguistic communities co-existing with each other, but they are separated by physical areas where each ethnic linguistic group resides. They are at the periphery of mainstream English speech communities. These speech communities only crossover for legal matters or for work. When younger generations learn English, they may integrate for periods of their day, but then return to their own speech community with families and elders, who are first-generation immigrants and remain in areas where their language is spoken, and their cultural products and practices are allowed publicly. Examples of these communities in New York, are found in upper Manhattan for immigrants from the Dominican Republic, Queens for various ethnic groups that divide by streets and sectors of the borough; China town is one that has remained historically isolated in the middle of the great city, and other ethnic areas of the Bronx and Brooklyn just to name a few within the urban New York. Recently more of this insular cultural societies have moved to upstate New York, populating entire areas with Mexican and other central American communities who arrive to work in agricultural jobs and seek to find better places to educate their children and afford better life quality (Leung, H. & Montoya, M., 2016).

Modified Cultural Pluralism

Modified Cultural Pluralism is a progression of the Insular Cultural Pluralism in the sense that dual identities are recognized for the second-generation immigrants. Those born in the U.S. of immigrant parents who have attended schools in the United States, grow up speaking two languages, consuming products from various cultures, including English mainstream mass and social media. These younger generations follow standards for social practices that allow them to be included into the “American” way of life; However, these people are still close to their immigrant parents and have not completed the entire assimilation demanded by English-centric communities at large. By the third generation, it is expected that their heritage language is lost, and the process completed to cross entirely to mainstream America. (See ideologies, Figure #1)

Immigration waves have continued and only through economic globalization at the end of the 20th century is when educational policy makers began to question the lack of cultural and linguistic understanding by new generations in the U.S. While the rest of the world spoke more than one language, in the U.S., youth were mostly fluent in one–English. Until recently, the larger “American” culture at large has begun an ideological shift that has started to change, moving overall attitudes towards valuing cultural plurilingualism. Yet despite this, the U.S. has a long transformation still ahead in practice. Schools are the places to begin such transformation towards linguistic pluralism. Linguistic ideologies have transformed in the U.S. as response to immigration waves and resources becoming available for a demanding society in need for integration. Within the Assimilation/Amalgamation ideology, the view regarding cultural and linguistic diversity is seen by the dominant culture as a problem. Norms are established according to the dominant group and others are judged inferior. Students from non-dominant cultural backgrounds must attend remedial educational programs to overcome deficits. The alternative proposes that if teachers and schools commit to a quest for accessing quality education for all, then differences may become simply viewed as differences, and not as deficits. If all educational leaders capitalize upon uniqueness in language and cultural backgrounds to teach students more effectively, the result would be genuinely accepting diversity as a new standard for creating a multilingual national unity. Teachers may see themselves guided by three orientations in relation to linguistic diversity in their school settings. First, when the non-dominant language (heritage or immigrant language) is seen as a problem, then assimilation to English and Americanization is favored. Second, when the individual’s native language is seen as a right, then bilingual programs are implemented, heritage and immigrant languages are maintained as well as the acquisition of the majority language. Third, when language is seen as a resource, then all school language programs seek to maintain heritage languages and promote second languages to the rest, dominant monolingual students, by the implementation of dual language programs throughout elementary and secondary (K-12) education for all students.

Language Ideology and Perceptions of Bilingual Education.

There are many factors involved in the formation of ideologies regarding bilingual education. First, appraisal of the bilingual classroom is often formed through its opposition with the monolingual classroom, which is perceived by students as their final goal, the ideal. The bilingual classroom becomes a step, a transition, and a remediation necessary to accomplish the goal of adaptation into the English language and society. Therefore the “bilingual” classroom is not about bilingualism, but a transition into monolingualism. Another perspective is that bilingual classes are viewed as inferior compared to the regular classes because of the people who comprise them; a the vast majority may perceive these students as uneducated immigrants belonging to lower socioeconomic classes. Moreover, students in these classes are placed homogeneously, erasing the differences between those who have been born in the U.S and lived within two languages all their lives and the others who are currently experiencing the immigration and acculturation processes. As a result, instructors do not give enough importance to the variety of performance levels within the students and, adding to the problem, in a lot of cases the teachers’ inexperience and mediocre knowledge of these students’ backgrounds lead them to categorize these students as deficient and problematic learners.

Reflective Talking Point

- What “Americanization” means to you? Were you encouraged to learn or maintain another language different from English while growing up? Were you encouraged to openly reveal your cultural background and uniqueness?

- Provide ideas on how to capitalize upon uniqueness in language and cultural backgrounds to teach students more effectively.

Video Resources:

- No Child Left Monolingual Dr. Kim Potowski at TEDxUofIChicago

- This is the new generation of Americans under a more open and inclusive ideology: “I SPEAK … AND ENGLISH, I AM AMERICAN”

Do Speak American? episodes 1-3. These episodes are available on the Films on Demand database. You can access the database via your school’s library. For example, if you are a SUNY Oneonta student, you can login at https://suny.oneonta.edu/milne-library and enter the title in the search bar.

Brief History of Bilingual Education in the United States

The U.S. has always been diverse linguistically. However, ideologies and beliefs behind this language contact have been shaped according to historical and political periods. Baker and Jones (1998) divided the historical moments of linguistic ideologies in the U.S. into three main periods: the independence period, the restrictive period. and the opportunity period. The independence period supported multilingualism and bilingual education towards dual maintenance. English was the dominant language in leadership, but other colonial languages were embraced. The same was not the case, however, for the indigenous languages of Native Americans, which the institutions of power sought to erase as part of an ethnic cleansing campaign of assimilation or removal. In The 18th and first half of the 19th century a permissive period of multiple languages followed; linguistic diversity was generally accepted and encouraged through religious practices, some emerging mass media (print), and within private and public educational settings.

Towards the second half of the 19th century in response to mass immigration into the United States, there was a sharp cultural turn towards ethnocentrism and English hegemony. This turn led to the restrictive period, which continued during the first half of the 20th century due to the great influx of new immigrants. These speech communities inundated the schools with multiple linguistic backgrounds and there was a national call for integration among the new arrivals. Integration and assimilation around the English language was presented as a symbol of loyalty to the receiving country. After the first world war, there was an anti-German sentiment, and English monolingualism became the response to this apparently Germanic threat. Linguistic intolerance strengthened and schools became the places where diverse people assimilated and integrated to the dominant speech community. The interest to learn foreign languages diminished considerably. Some institutional policies reinforced this need for integration. In 1919, the education system adopted a resolution that recommended all schools, private and public, to make English the language of instruction (Baker & Jones, 1998). Schools began to make English the dominant language of instruction for all content areas in the years that followed. By 1923, thirty-four states decreed that English must be the language of instruction in all schools. This first half of the 20th century, emphasized compulsory attendance to public schools. Financial government assistance to private or parochial schools, which may have had some bilingual programs, was eliminated completely. Despite these policy changes, there were conflicting messages top- down regarding linguistic tolerance. This same year, the Supreme Court declared unconstitutional a law in Nebraska that prohibited foreign language teaching to elementary school children and declared that learning and acquiring knowledge in a foreign language would not affect the health, moral development, or comprehension of the learner. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court did not extend its ruling to support bilingual education or the use of bilingualism for communication in the public-school context. Colonial European languages were not perceived as “ethnic immigrant languages”, but as “foreign languages.” These languages were incorporated into the curriculum as another school subject. Schools and curriculum did not attach any ethnocultural value of these languages to the history of the U.S., and the Indigenous ethnolinguistic speech communities were perceived as unconnected/external to the dominant mainstream culture wherein First Nations, or Indigenous, peoples were not considered as truly American citizens. During the second world war, Jewish and Italian immigrants were integrated into the English dominant school system. Additionally, these two immigrant groups were granted a special permit allowing the use of their native languages for content instruction as a transitional model as the students assimilated into the English-centered curriculum; however these transitional models did not foster bilingualism and biliteracy. Students’ success was measured by how rapidly they embraced the English language and the new U.S. cultural practices.

The second half of the 20th century shifted to an opportunity period in terms of including multiple languages in the school curriculum. After 1957, when the Russians sent their first spaceship outside of the planet, the U.S. political leaders began to question the country’s capacity to compete in an international market and technology. A debate that questioned quality of education, scientific creativity, and recognition that other languages must be learned quickly followed. As mentioned in an earlier chapter the federal government mobilized funding for the National Defense Education Act of 1958. As a result, U.S. national defense agencies promoted foreign language teaching, and multiple pedagogical strategies to teach other languages rapidly became popular, mostly during the Cold War period. This mostly highlighted the need for other languages in terms of national security, but not much for the overall population.

This restrictive period continued until the 1960s and became an important topic thereof for the state policies in the United States. During the 1960s, the issue of bilingual education was brought up for re-evaluation by the human rights movement, as a signal towards ethnic tolerance and a possibility for social integration. The arrival of a large Cuban population in Florida during the 1960s promoted the re-institution of bilingual education as a temporary strategy to assist the great numbers of students in schools that spoke Spanish and were waiting to return to their homeland after Cuba would become again normalized and Fidel Castro’s communism defeated. However, this never occurred and, as a result, bilingual education evolved to serve the linguistic populations in need. These programs became supported by federal policies providing financial assistance for growing bilingual programs in Florida. This usage of Spanish for content instruction in Florida was a transitional model with the purpose of learning English and integrating. By the third generation, Cuban-Americans were slowly losing their proficiency in their heritage language. Following Florida, other states considered the importance of bilingual transitional instruction to assist students that spoke other languages at home and had academic difficulties in various subjects. Bilingualism in schools was implemented as a “crutch” while the students may advance, but soon to be abandoned when the learner became fluent in English.

During the 1970s, educators and parent organizations questioned the equitable access for all students for linguistic minorities. English as a Second Language (ESL) programs proliferated to fulfill the needs demanded by immigrant families to access equal quality education. The Supreme Court declared immersion programs founded on “sink or swim” models of education unconstitutional as they put some children behind as a result. Other languages were allowed in school and ESL programs were developed and instituted, however as remedial programs to assist the “issue” of multilingualism in schools. In response to the implementation of transitional bilingual programs in the 1970s and 80s, English-only movements became antagonistic into the ideas of equity and the advocacy for unique languages and the cultural assimilation imposed upon minority groups.

It is important to highlight that scholarly research on the benefits of bilingualism was not advanced during this period and people just supported their opinions on the ideology of bilingualism as a phenomenon, which resulted in confusion and a significant delay in content knowledge of basic schooling for immigrant children. As academic studies started to demonstrate the cognitive benefits of bilingualism, initiatives in pedagogical approaches began to be discussed. Teachers and communities debated: the amount of each language for instruction, the efficacy of pull out versus push in programs, the allocation of resources available, and the need for professional development for teachers that were mostly monolingual. New York schools needed bilingual teachers and programs that sought to recruit Puerto Rican bilingual teachers were implemented . There was a wave of Puerto Rican professionals moving to New York City to fulfill this need of human resources in New York City Public Schools. Other professional immigrants from Latin America took advantage of this opportunity and most of the ESL or Bilingual support was done by adult immigrants from Spanish speaking countries. Nevertheless, this was not guaranteeing a change to a pluralistic view of multilingualism and heritage language maintenance.

On the contrary, the Reagan administration was hostile towards bilingual education arguing that such programs which allowed for heritage language maintenance and use of the heritage language for instruction did not foster integration and assimilation into the English dominant labor market in the U.S. By 1985, financial support to bilingual educational programs switched to ESL monolingual instruction programs. The issue was mostly a political debate that did not allow teachers to assess and propose effective ways to teach content using the native languages of the immigrant children. In the meantime, there was a surge of linguists and other scholars in the social sciences investigating the cognitive effects of bilingualism and the benefits of using a strong language to access the other language system in order to develop biliteracy. All of theory and research was too new for politicians of the time to understand; therefore,language policies were based on flawed misinformed ideas based on ideologies and not scientific studies. Therefore, the federal government passed the responsibility about the decisions on bilingual education to local state politicians. Finally, after several academic studies began to demonstrate the benefits of bilingual development, a shift in ideologies towards valuing cultural plurilingualism has recently begun in earnest. Nevertheless, there has been difficulty into coming to consensus on best practices in teaching value and maintaining and celebrating multilingualism in the U.S. as well as to teach children from multilingual and multicultural backgrounds.

Bilingual Education after 1980

Brisk (1998) presents one of the earliest extensive works on bilingual education (1998). Her work describes the existing models in English as a second language and bilingual instruction according to learning objectives, type of students served, languages in which literacy is developed, and language of subject matter instruction. Brisk adds that bilingual models are divided between those that strive for fluency in the second language, English, and those that have as a major goal fluency in two languages. When comparing the two models, the English as a second language/ bilingual structured immersion programs are perceived as subtractive because the development of the second language is done at the expense of the native language. The subtractive model’s success is measured by how quickly the students exit the program. On the other hand, bilingual programs that support fluency in two languages are additive since they foster development of both, the second and native languages. Additive models focus on dual language development as well as academic preparation. Brisk’s analysis of the factors affecting bilingual programs describes contradictory results: students succeed in programs that start in the second language when the students are members of language majority, have a strong basis in their native language and positive language attitudes, hear and see language constantly used in their environment, and eventually take language courses in school. Programs fail when students belong to language minorities with weak literacy background in their native language, limited use of the language in the larger environment, and poor attitudes toward their own language. According to the author, the concern is not a choice of language, but the characteristics of the population served.

Also, in early research on bilingual instruction, Torres (1990) differentiates between the pluralistic and the acculturation models of bilingual education programs: cultural pluralist approaches measure the success of bilingual education programs by the extent to which they help maintain and cultivate native languages and cultures; supporters of cultural pluralism advocate maintenance of bilingual programs that treat both languages equally so that content subjects are taught in both languages. One of the aims of bilingual education should be to demonstrate that heritage languages are valid instruments of communication, and literacy development, the same as English. Children in pluralistic language models develop more positive attitudes about their cultural heritage, their parents, and their first/home language. In opposition, there are the acculturation models which slowly limit the use of native languages and cultures. Torres argues that these subtractive bilingual education models serve to make acculturations smoother supporting English monolingualism as a norm.

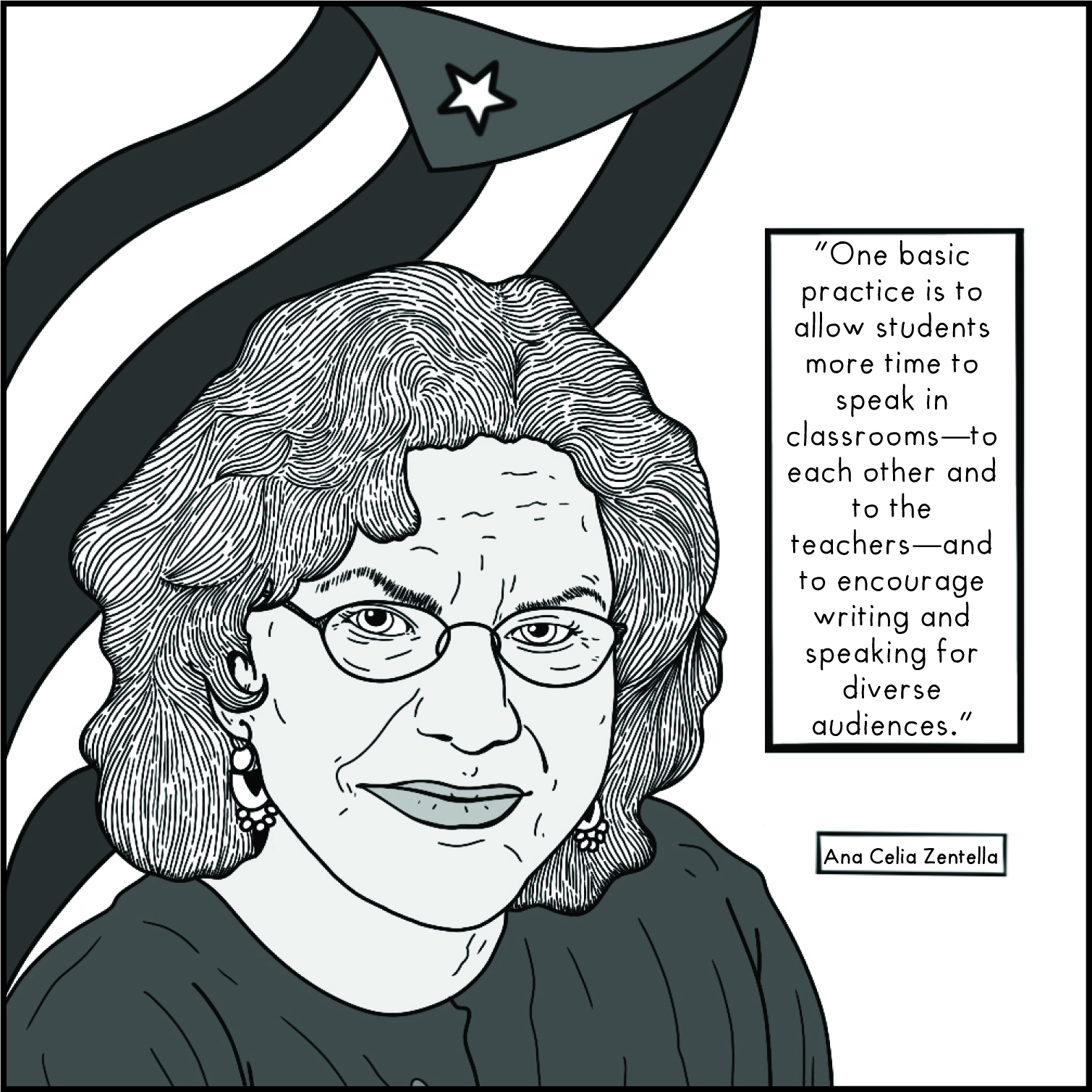

Meet the theorist

Ana Celia Zentella was born in the South Bronx, New York City to a Puerto Rican mother and a Mexican father. Growing up in the 1950s, she was exposed not only to multiple languages but also to multiple varieties of Spanish in New York. She attended Hunter College, CUNY in the Bronx as an undergraduate, obtaining a B.A. degree in Spanish. She went on to complete a M.A. in Romance Languages and Literatures at Pennsylvania State University, and obtained a PhD in Educational Linguistics in 1981 at the University of Pennsylvania, with a dissertation titled “Hablamos los dos. We speak both”: Growing up bilingual in el barrio. Dr. Zentella is a linguist well-known for her “anthro-political” approach to linguistic research and her expertise on multilingualism, linguistic diversity, and language intolerance, especially in relation to diverse U.S. Latino languages and communities on the East and West coasts. An early member of the Department of Black and Puerto Rican Studies at Hunter College, she is now Professor Emerita of Ethnic Studies at the University of California, San Diego. Her 1997 book Growing up Bilingual: Puerto Rican children in New York was honored by the British Association for Applied Linguistics and the Association of Latina and Latino Anthropologists of the American Anthropology Association. Zentella’s research adopts a political perspective on linguistic anthropology that places language in its social context and acknowledges that no language exists without being subjected to power. Much of her research focuses on U.S. varieties of Spanish, English, and Spanglish, practices of language socialization in familias latinas, and the societal impact of “English-only” laws. In 2023 she was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

The decade of the 90s was fruitful for scholars in the field of bilingualism, and among them Zentella (1990) presented another perspective to the issue of bilingual education vs. monolingual methodology of submersion. This scholar states that the submersion methodology functions well when it is part of an educational experience to expand the linguistic and cultural repertoire of the students of the majority group, but submersion does not work properly when it intends to eliminate the language and culture of the minority group. Another problem acknowledged by Zentella is the role of immigrant parents for language input. It was common, at the end of the 20th century, to hear teachers encouraging parents to speak more English to their children without understanding that it would be of more value if parents spoke the language that they know best. Providing heritage language experience to the child helps them to develop linguistic skills, such as language registers and variations, including the construction of logical arguments. However, this linguistic contribution by parents is not stimulated since in most cases the parents’ speech is judged as inferior to the academic standard languages used at schools, therefore not productive for the development of language acquisition.

As teachers’ professional development became more linguistically inclusive turning into the new millennium, and assimilation ideologies become slowly replaced by pluralistic views about diversity, schools begun to transform into “affirming classrooms” leading to “affirming societies” in which racism, sexism, social class discrimination, and other biases are no longer acceptable (Nieto, cited in Reagan, 2009). Therefore, previous ideologies underlying many school policies and practices that were based on flawed ideas about intelligence and difference were questioned; curriculums and pedagogical strategies, today, must consider differentiation, multilingualism and multiculturalism in all content areas, and teachers are encouraged to learn about the cultures and languages of their pupils. In addition, if schools support the use of heritage languages, the linguistic loyalty sentiment by parents who would like their children to maintain cultural ties to their origins, adds to the support needed by their children to become and maintain a balanced bilingualism while encouraging their monolingual peers to learn other languages and cultures.

Acquiring languages is not the same for all learners, it depends on many factors from individual aptitudes to contextual situations that may act as emotional filters, which may affect motivation in both directions, negative and positive. Brisk (1998) explains there are multiple situational and individual factors that affect students’ school performance. Situational factors, including linguistic, cultural, economic, political, and social, influence how students of a particular ethnic group are viewed by educators and peers. Families play an important role in language development, identity formation, and positive motivation achievement. Learners’ backgrounds such as language spoken at home, cultural practices, and parents’ level of education influence how bilingual students’ performance in school. Families’ perceptions of their children’s linguistic needs may oscillate between the perception that bilingual programs may slow down their children’s immersion into the community’s dominant culture, hence they do not see these programs as beneficial to provide the transitional time. Typically, these are families who already reside within the U.S and would prefer immersion programs that prompt their children to function rapidly among the mainstream culture for their own success, at the expense of losing their home language. Families that seek full immersion into the dominant culture, often see their immigration experience to the U.S. as an opportunity to leave behind any suffering of the past. On the other hand, there are families that view the bilingual education received by their children as the only path for their children to fluent literacies in their heritage language.These fluent literacy practices help children to write and read in their parents’ native language and provide opportunities for parents to help with their homework in addition to encouraging maintenance of the heritage language while immersion in English. These families often consider a possible return to their homeland and prefer to maintain strong ties to their culture including their children born in the U.S.

Reflective Talking Point

- Teachers and parents interactions are necessary for the development of their children’s academic knowledge, part of this is biliteracy/bilingual development. How would you approach different parental perceptions about their children’s needs to maintain their heritage language while learning English? How can teachers use families to embrace multilingualism and multiculturalism?

Language Attitudes

Language attitudes are motivated by several instrumental and integrative dimensions. According to Colin Baker (1995) there is the instrumental motivation, which reflects pragmatic, utilitarian motives. Language becomes the catalyst characterized by the desire to gain social recognition or economic advantages. It is self-oriented, individualistic, and would seem to have a conceptual overlap with the need for achievement. On the other hand, integrative motivation is mostly social and interpersonal in orientation including the need for affiliation, and a desire to be a representative member of a speech community. Teachers ought to investigate their students’ motivations towards heritage language maintenance or rejection. This often becomes overt after middle school years when there is a concrete academic offer to study LOTE (Languages Other than English) languages, and heritage speakers find themselves questioning their proficiency in the home language and their desire for improvement or abandonment. It is important to consider when investigating the participants’ language proficiency or desire to improve it, their attitude or motivation to learn a new language or maintain their home language is independent of their linguistic aptitude (capacity to easily acquire language). Aptitude relates to the level of difficulty, the ability, that a person has towards learning a new language and becoming a bilingual proficient speaker. This varies among people with diverse learning experiences.

Participants’ instrumental and integrative orientations may develop positively or negatively. For example, some statements that reveal instrumental positive are:

I want to preserve my heritage language. Knowing Spanish is necessary (good) to find a job later, specifically teaching it or in bilingual school environments.

On the opposite side, the statements that reveal an instrumental negative attitude are:

Heritage languages are not necessary to survive in the U.S., Our parents needed to learn English to help us with schoolwork and social adaptation. Preserving Spanish at home led to confusion in learning and developing English proficiency.

The integrative positive statements are:

Knowing Spanish is necessary (good) to relate to my family; Schools must help to preserve heritage languages and not penalize its use; Parents must demand the use of heritage language at home.

Integrative negative statements are:

A common language, in this case English, is more useful for everyone to learn at school. Having multiple languages in a classroom is chaotic and difficult to deliver content knowledge, it requires more financial resources.

There are five determinants on the development of language attitudes that are basic for the required observation when encountering heritage speakers in the classrooms. First, age; the various types of language input and experiences, positive or negative, the student has received up to their age while growing up. Second,the child’s caretaker while growing up in a multilingual or bilingual setting, who is or was responsible for the child’s upbringing, and the kinds of language input received by their mother, father, or other relatives. In addition, there is also the consideration of caretakers’ educational levels and their own proficiencies in other languages or dialects spoken. Third, schooling and educational experiences; what kind of formal or multilingual/bilingual integrated curriculum, and extracurricular activities have been part of the students’ experiences that may produce favorable attitudes, or may change their language attitudes; therefore, increasing or decreasing proficiencies in home languages. For example, parents’ choices of schools and programs available to them within their communities of residence. Fourth, ability; if the learner presents confident ability towards learning languages and literacy development, there is higher achievement proficiency and ability in a language as a result of a more favorable attitude. Often this ability depends on other determinants that influence the linguistic attitude towards multilingualism or bilingualism. Lastly, there is the linguistic active speech community involvement. This is observed throughout the experiences available in reference to religious services, entertainment, communal activities in which the main language used is the heritage one.

Descriptive Research Activity:

Use the Web and your previous knowledge of an Ethnic Speech Community that resides in New York. Describe which physical spaces exist within these communities where the heritage language is used for interaction and transactions, for example stores “bodegas”, churches, financial offices. Describe if these communities have changed the names of streets, and places within their physical environments. Also dig into the availability of mass media in their heritage language (TV, printed news, radio). Find pictures of these examples in the communities you describe and share with classmates.

Festinger (cited in Baker, 1995)contributed to the development of Cognitive Dissonance Theory (CDT), which states that language attitudes must be in harmony; and when inconsistent messages about the importance of their home languages are received, cognitive tensions may rise. Learners may suffer conflicting experiences growing up bilingual that result in contradicting attitudes that eventually end up affecting their biliteracy development and bilingual engagement. The formal education imposition towards standard English or the standard variety of their heritage language, may discourage them to retain home dialects and perceive dual identity upbringing as negative to be successful in mainstream societies. Consequently, young learners may be discouraged at home to use their heritage language actively among parents and extended family. These learners develop a passive proficiency of the heritage language being only receptors, comprehending the home language but not actively using it in speech acts. According to Silva-Corvalan (1997) it is important to consider for the analysis of a bilingual upbringing, and eventually bi-literacy development, the measurement of students’ proficiency and comfort level by revealing children’s previous exposures of their heritage languages. The language proficiency assessment should question the following to determine if the heritage language is underdeveloped or interrupted; such as, if the home language development was suspended due to an immigration experience to the U.S. or reinstated by returning back to their country of origin, i.e.., back to the parents’ country, which stopped the immersion of English. This change of speech community is often experienced with lack of linguistic exposure in one of the languages. Thus, this change results in learners’ loss in expressive language (speech, gestures, or writing) or simplification of language skills. In other words, losing command of a variety of grammatical forms and/or vocabulary in their linguistic repertoire.

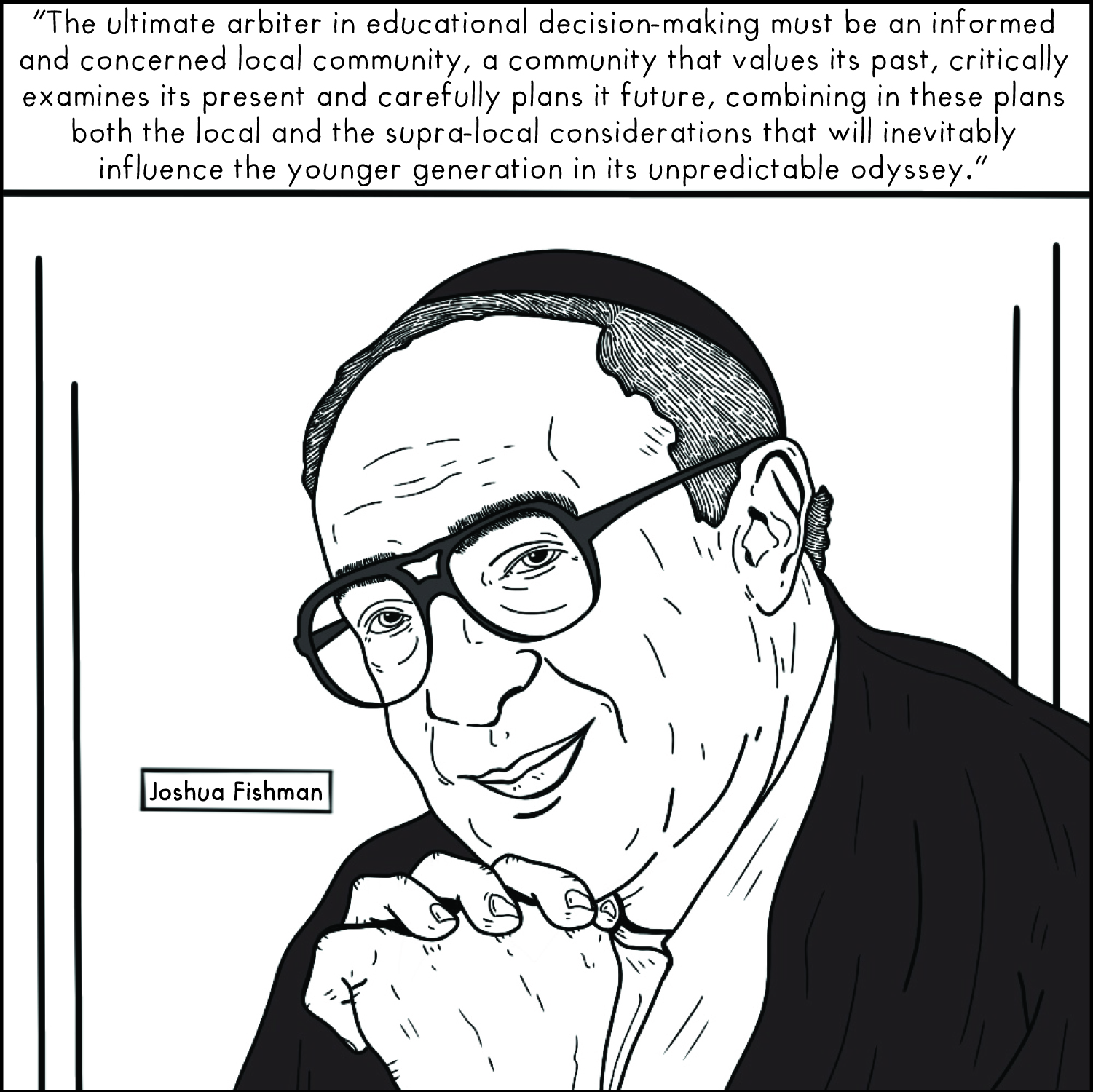

Meet the theorist

Joshua A. Fishman (Yiddish name Shikl) was born on July 18, 1926, and raised in Philadelphia. He died on March 1, 2015. He was an American linguist who specialized in the sociology of language, language planning, bilingual education, language and ethnicity. He attended public schools while also studying Yiddish at elementary and secondary levels. He studied Yiddish in Workmen’s Circle Schools, which emphasized mastery of the Yiddish language along with a focus on literature, history, and social issues. He attended the University of Pennsylvania, majoring in history and psychology. Dr. Fishman completed his Ph.D. in social psychology at Columbia University in 1953 with a dissertation entitled Negative Stereotypes Concerning Americans among American-born Children Receiving Various Types of Minority-group Education. From 1955 to 1958, he taught the sociology of language at the City College of New York while he was also directing research at the College Entrance Examination Board. In 1958, he was appointed an associate professor of human relations and psychology at University of Pennsylvania. He subsequently accepted a post as professor of psychology and sociology at Yeshiva University in New York, where he would also serve as dean of the Ferkauf Graduate School of Social Sciences and Humanities as well as academic vice president. In 1966, he was made Distinguished University Research Professor of Social Sciences. In 1988, he became professor emeritus and became affiliated with a number of other institutions. Fishman wrote over 1000 articles and monographs on multilingualism, bilingual education and minority education, the sociology and history of the Yiddish language, language planning, reversing language shift, language revival, language and nationalism, language and religion, and language and ethnicity.

According to Fishman (1997),language shift occurs when exposure and prestige is associated with the dominant language, in case of the U.S. context would be English. However, reverse shift may occur when there is an immersion in the immigrant speech community, either in the U.S. due to immigrant communities from the same linguistic background living in clusters of the similar origins and common varieties of one language, or it may occur if the individual is sent for extended time or yearly visits to the original speech communities outside of the U.S. to their parents’ country of origin. An individual may become orally proficient in both languages due to exposure, yet oral proficiency does not transfer easily to literacy. Command of biliteracy depends on educational programs available, support for heritage language maintenance in dual programs since elementary grade levels, as well as the family’s determination in preserving their heritage language. There are caretakers that insist in the active use of their home language in the private domains, whereas there are others that prefer that their children immerse quickly into the dominant language to obtain opportunities given to native speakers and avoid discrimination in some areas where assimilation ideologies may be still strong. Recently, globalization has demanded intercultural communication that includes the use of more translingual practices. This demand leads to a societal linguistic insecurity among monolingual speakers in the U.S. where more “nativist” governmental policies may be used to highlight the dominance of English, or in opposition, more pluralistic approaches may encourage the creation of quality bilingual/multilingual education in public schools.

Learning Applied Descriptive Activity

Find and interview a person who has immigrated to the U.S. before 10 years old, or someone who was born in the U.S. of immigrant parents (any linguistic speech community) and generate a linguistic profile fulfilling the table below:

| Dominant language | Language(s) learned at

home first |

Language learned at school settings primarily | Age of acquisition of a second language or bilingualism early development | Language use domains:

home, school community (which language is used where) |

Linguistic Ideologies:

Messages delivered by people in schools and community members about bilingualism and heritage language maintenance. |

|

|

Reflective Talking Point:

- Do you share common experiences with the person you interview? If both of your experiences are different, describe possible inequalities experienced by either person, you or the interviewee?

- Share your profiles with peers.

Different Types of Learners in the Bilingual or English as a New Language Classrooms

The definition of the heritage language learner and its distinction from the immigrant child learner is necessary to clarify for addressing the specific challenges in the classroom. These children’s needs differ in terms of new language acquisition or heritage language maintenance. There are two main types of students encountered in the English as a New Language (ENL) or bilingual classrooms: first, there is the heritage language learner, born in the U.S. or brought into the country before school age, and second, there is the immigrant child or native speaker of another language different than English, who arrives in the country after having started literacy development in a monolingual setting outside of the U.S school system. The educational demands of these two types of students vary. The heritage speaker has always been immersed in a dual linguistic context. This child has received English input, passively or actively, through various experiences in different speech communities, mass media and entertainment, and often by older siblings who bring the societal language to the home environment, making it the main language of communication among newer generations. Consequently, English is not considered a “new” language for this learner, and cultural adaptation may not be a traumatic issue for these learners, they have lived within two cultures and languages since birth or early childhood. On the contrary, the immigrant child encounters not only a new language, but a new society that pressures them to adapt and understand, often suffering from cultural shock while they transition. This immigrant child may already bring established literacy in another language that can be a transferred skill, useful in learning a new language; whereas the heritage speaker has received oral input in both languages, but not necessarily may have developed literacy in the home language and cannot use it as support to learn English.

Acquisition of bilingual fluency and heritage language maintenance is experienced differently depending on the child’s first contact with the societal language and attitudes held by the community. The students’ attitude toward the heritage language and their academic success is deeply related to their perception of the socioeconomic class to which they belong. In addition to academic and linguistic success, attitudes affect the chances for social integration.

“In the United States assimilation is seen as a precondition for social, political, and economic participation. Although most immigrant groups aspire to social and economic incorporation, they do not all have the same options. Some succeed in assimilation into mainstream middle-class America, others are socialized with poor native-born Americans, and still others choose to incorporate into an established ethnic community” (Brisk, 1998, p. 51).

Integration into the dominant English mainstream communities depends on the ethnic and linguistic diversity encountered in the places the learners reside. There are some parents who purposely moved away from predominantly immigrant and multilinguistic neighborhoods to provide a “better” American environment and education for their children. Nevertheless, some of these families do not neglect the importance of their heritage language as an identity value and use it in the home setting; These families divide the private experience from the public one as a strategy to motivate their children to preserve their native culture and language. However, it may occur that children of diverse ethnic and linguistic backgrounds find themselves competing with students with more affluence and privilege in these less diverse communities; therefore, the students may become discouraged to succeed, unless they find leaders in the educational system who encourage them to maintain pride in their identity and embrace the language and culture of the majority. On the contrary, other families that decide to remain within their own ethnic community, consider that speech community support is important for their daily survival and the upbringing of their children; for them being around others of similar ethnic backgrounds reinforce cultural values, such as respect for elders, religious rituals, traditions, and heritage language use at home during family reunions. Intertwined private and social communal practices aid families to overcome discrimination from mainstream environments that might discourage their kids from continuing into higher education. Brisk analyzes how social factors affect the interactions between schools and students and ultimately students’ performance.

“Unfortunately, most bilingual individuals suffer social prejudices that thwart their aspirations. Societal pressures force immigrants to make difficult choices between home languages and English as well as ethnic and American culture. Individuals with many of these social characteristics that predict failure can still succeed without abandoning home language and culture thanks to personal, family, and school resources that support them in their struggle” (Brisk, 1994a, in Brisk 1998, p. 52)

Educational institutions in the United States need to become spaces responsible for assisting in the constructive and creative development of linguistically diverse identities. Therefore, the relationship and understanding that educators establish with multilingual learners and young immigrants is extremely important. Linguistically diverse students arrive to the U.S educational system with a distinctive cultural background. These learners need to achieve literacy fluency in the community language, English, and use their native/heritage language proficiencies to advance, to encode (read) and encode (write) text in order to not fall behind in various contents in elementary and secondary classrooms. Teachers ought to become more sensitive to cultural manifestations and identity construction while allowing bilingual acquisition to evolve naturally and strengthening mental connections in their learning process. Zentella (1990) added that in early times of bilingual advocacy, schoolteachers played an important role in students’ maintenance of their home languages and to help their students understand that they may still use their native language while learning English, emphasizing that doing so will not be detrimental to them.

Early development in bilingualism and biliteracy presents a complex issue for professionals who perhaps are not prepared for such an instruction and who suddenly have to adapt their classes for individuals who are linguistically diverse. Many school districts in various parts of the country, such as New York and California, responded to the impact of this population shift by implementing transitional bilingual education programs as well as special ENL instructional programs. The secondary and post-secondary institutions have also been affected by this population shift in linguistically diverse students. This has encouraged educators to re-design teaching strategies that are inclusive to linguistic diversity, encouraging new teachers to learn other languages themselves or use technology available to be able to help their students. Linguistic diverse classrooms nowadays, include a main classroom teacher assisted by a certified ENL or Bilingual teacher. Schools differ in their approaches due to demographics of immigrant populations and the human resources available. Another challenge is counting on textbook publishers to develop bilingual/multilingual materials. School linguistic practices are also influenced by the language used at homes. If heritage languages use is strong outside the school, educational policies cannot ignore such a reality and must include language programs that address the sociolinguistic dynamic of the community. Brisk (1998) adds the “status of languages and their speakers, status of dialects and subgroups within ethnic groups, socioeconomic level, race, gender, and reasons for being in the United States shape attitudes and expectations of teachers toward bilingual students” (p. 49). Language educational policies must consider the preparation of teachers to understand such reality of language minority students.

The difficulty to maintain bilingualism across generations is well assumed, even when societal bilingualism is stable. Many scholars and students are pessimistic about the maintenance of heritage languages in an environment surrounded by societal pressures and misconceptions of the benefits of bilingualism, or multilingualism, in our society. The classroom by itself is limited in accomplishing this goal; therefore, it is important for educators to listen to what parents believe and how they see their children’s future in the country where they had immigrated as well as their own children’s well-being. Silva-Corvalán (1997) describes important findings of her research about the Spanish spoken in Los Angeles and its sociolinguistic aspects. She observes the situation of Spanish maintenance or shift to English. For example, there are more publications in Spanish, more TV programs for Spanish speaking audiences, numerous companies publicize in Spanish and a great deal of institutions and organizations provide special services in Spanish. Within the family domain, older children are most likely to preserve the home language; however younger children experience language contact earlier in life and due to the less strict strategies by parents to encourage language maintenance, the younger children prefer English over Spanish during their language development. Silva-Corvalán confirms these patterns based on her studies. Generally, the linguistic attitudes by Hispanics to preserve their home language and culture is positive, but their positive attitude becomes conflicted with a lack of concrete compromise to do something for the Spanish language and the ancestral culture. On the other hand, recent immigrants have stimulated the frequent use of Spanish in the work environment. These cases motivate second-generation speakers to re-learn their home language.

English Language Learners and Emergent Bilinguals, Who are They?

English Language learners (ELLs), or emerging bi/multilinguals (EBs), have many variations depending on their bilingual upbringing, dialect variation, home language linguistic ideology status, linguistic background, parents’ level of education and immigration history. However, Escobar & Potowski (2015) have identified two main types of emerging bilinguals. First, there are the interrupted/reduced bilinguals: students who immigrated to the U.S during sometime in early childhood and adolescence (ages 7-15). They were immersed in a different culture and linguistic environment at early schooling, and were not encouraged to maintain their home language. Second, the balanced/additive bilinguals: students who were born in the U.S of foreign language speaking parents. They have lived within a different language and cultural environments between home and school. Some of these children are encouraged to maintain their home languages because they became language brokers for their immigrant parents or because of linguistic loyalty in their households and immigrant communities. The experiences that these two types of students have in schools add to the pedagogical research on ideologies regarding bilingual education. One study (Montrul, 2013) implies bilingual educational programs are not about maintaining bilingualism, but, rather, a transition to monolingualism, which sacrifices heritage languages. Moreover, students belonging to these bilingual classes are not only part of the disadvantaged social class, they are perceived as citizens which necessitates their assimilation into the mainstream society. However, this becomes troubling because, within the norm and academic development in the school system, the problem remains with the students and not in the implementation of the bilingual program.

Another interpretation of what occurs inside the bilingual classroom is erasure. Students in bilingual classes are placed homogeneously, erasing the differences between those who have been born in the U.S. and lived within two languages all their lives and the others who have experienced the immigration and acculturation processes upon immigration arrival. In addition, places of origin, as an important factor of uniqueness, are erased to form one distinct cultural group among most of the school population, homogenous within themselves. As a result, instructors do not give enough importance to the variety of languages, dialects, and proficiency levels within this student population. Adding to the problem, often teachers’ inexperience or perfunctory knowledge of these students’ backgrounds lead to the deficit approach which categorizes these students as deficient and problematic learners. The diversity within the students in these bilingual classrooms is lost to hidden curriculum to assimilate these students into a dominant homogeneous society. ELLS and EBs are not homogenous at all. They differ by the manner their languages were acquired. There are three main types of bilinguals according to input exposure (Romain, 1995): the coordinate bilingual who learned the two languages independent in separate environments, and whose fluency vary according to intensity of input in various settings and topics discussed; the compound bilingual describes individuals whose languages are interdependent and learned in the same environment allowing for intense code-switching; lastly, there is the sub-coordinate bilingual for whom one of the languages is dominant and acts as a filter for the other one. This last type of bilingual interprets words of their weaker language through the stronger one, and it is mostly known as a passive bilingual.

In terms of bilingual behavior, children initially develop functional grammars combining the two languages to communicate. The first stage of development is pragmatic and semantic. In other words, meaning relations occur first where words are interchanged (codeswitched) to express communicative needs. Children want to express messages and do not have the syntactic structures, so they would create their own bilingual mixed grammar to communicate their needs. Then syntactic development, structures, occur later when children begin to separate the two languages, and this does not occur until the child initiates the literacy development process and awareness of their two bilingual settings is more obvious, often when they are registered in formal schooling. Bilingual children start their speech production later than a monolingual child, yet cognitive development is the same as a normal monolingual child. Grammar in both languages is creative while learning the rules and depends on input from various domains. Here is a speech example of a four-year-old child, just before entering formal schooling; mother and child are arriving at the public library early reading program:

Mom-¿dónde llegamos Ozzy? [where are we?]

Ozzy-The story house

Mom- Y en español? [in Spanish?]

Ozzy- House de stories [English vocabulary is combined with Spanish structure]

As this youth of second-generation immigrants develop bilingualism and maintain their parents’ native language, they develop a new variety of this heritage language in the United States, which differs from the monolingual dialects from their countries of origin. This new multilingual variation in the U.S. is formed by language and dialect contact in the new country (Escobar-Potowski, 2015). In youth, it becomes an interesting code-switching output, with its own grammar, not in violation of the syntactic rules of the languages involved. Language code-switching becomes a unique marker of identity for these speakers in mainstream societies.

Reflective Talking Point

Children that use minority/heritage language at home, experience their first encounter with the majority language at school. For heritage languages to be maintained and balanced bilingualism encouraged, it needs an opportunity to be fostered at the home environment and support from the school setting and communities at large.

- Do you think it is important to maintain heritage languages? Why?

- What could you do as a teacher or a professional to ease the impact of the change experienced by the immigrant child or 2nd generation heritage speaker?

- How could you support heritage language maintenance from your position in the school?

Language Domains and Family Input in Bilingualism

Domains are understood as the environments where individuals receive language input and interact within speech communities. Wide domains include home first. In this domain it is necessary to analyze relationships and family roles among mother, father, siblings, and other relatives in the household. Birth position in the family is important since the older child usually receives more heritage language input, and the younger children are exposed to the mainstream language as the older ones attend public schooling first and bring it to the home environment using it with younger siblings. Second, there are the schools and the community of residence domains. These two impact the interactions that an immigrant or heritage speaker, born in the U.S. child, has with the institutional language. If the community has a large population of immigrants from the same linguistic background, then the heritage and the dominant language compete, fostering bilingualism. On the contrary, if the community is anglophonic and there is less language diversity, the child most likely will transition. There are other types of communities within urban multicultural/linguistic communities, these are encountered in the boroughs of New York City. In these areas, residents separate in their own ethnic clusters to network and find support from each other. On the streets, multiple ethnic products are found mediated by multilingual interactions bridged by English usage as the community language. Young heritage speakers in these urban areas have a more rigid use of their languages making one private and the other public. The heritage language becomes part of the private domain and English takes the public domain.

In recent research on rural upstate New York communities of Hispanic agricultural immigrants (Montoya, 2015, Montoya & Leung, 2016, & Living Bilingual Blog, 2024 ). This research observed an interesting phenomenon of heritage language maintenance within communities where Hispanic immigrants live in clusters surrounded by anglophonic monolingual communities. This occurs due to the need to maintain ethnic identities where these identities survive from mutual support from each other and affirmative pride in their country of origin, which strengthens their community network. In these communities, inserted in rural NY, groups of people from the same origins are found, sharing public communal religious practices, cultural entertainment brought by them to the wide anglophonic community during Mexican holidays (public dances and food selling at public markets). This phenomenon, if embraced by the mainstream English speakers, integrates heritage speakers’ dual identities. For more positive outcomes, it is usually the role of teachers in these rural areas who have been observed providing care and support.

There are cultural symbolic markers that serve to foster dual language development. The music industry and social media is foremost the piece in fostering heritage language maintenance as it provides a unique skill to the children growing up with two languages that differentiates them from other young members of their mainstream communities, serving as identity markers that teenagers use to feed their networks of bilingual/code switchers friends. Along with the influences that these domains may have in a heritage child, there are the motives for retention: first, “root” identity passed by immigrant parents who are loyal and proud of their ethnicities; second, need for association with networks of friends that are multicultural/multilingual, and lastly, recognition of the heritage language as an important skill to later secure a unique position in the job market. Language retention is observed to happen when there is fluid communication with extended family members and others in the community who are new immigrants into the U.S. Zentella (1997)revealed from her studies of the Puerto Rican community in New York, that those who favor the retention of Spanish are children who have both parents belonging to the group of first-generation adult immigrants. Nevertheless, there are other factors that relate to parents’ support of their children’s bilingualism; for example, if there is an assumption that if their ethnicity and language is retained, their children’s social advancement may be penalized.. This preoccupation is factored by parents’ level of education and their own and other family members’ experiences of discrimination. Any kind of unpleasant or unjust situations that parents may have experienced by their lacking English fluency, will possibly perpetuate their own negative attitudes about immigration and bilingualism, which affects their assimilation into the U.S society, linguistically and culturally.

Reflective Talking Point

Families are so different from another in composition, cultural beliefs and practices, routines, levels of education, and access to products and services, and documented immigrant status in the U.S. All these factors may determine their capacity to assist their children to improve and take opportunities.

- How can teachers support families to help their children succeed considering the diversity within them? Provide concrete examples.

Models of Education for English Language Learners

Sonia Nieto (2017) defines multicultural education as a five-stage process (The five levels of multicultural education.) It departs at the monoculture level when one is only familiar with an immediate cultural input similar to self; then difference is noticed and tolerance is civilly required by institutions such as schools so humans may cohabitate with one another. Not until authentic and honest interaction occurs, one comes to experience acceptance of the Other; respect ought to follow by learning about the others’ perspectives and histories until affirmation and solidarity are reached.

The ideologies underlying many school policies and practices are based on flawed ideas about intelligence and difference. If we want to change the situation, it means changing the curriculum and pedagogy in individual classrooms, as well as the school’s practices and the ideologies undergirding them. That is, we need to create not only affirming classrooms, but also an affirming society in which racism, sexism, social class discrimination, and other biases are no longer acceptable.” ~ Sonia Nieto (cited in Reagan, 2009)

Through our U.S. educational history, immigrant children, or U.S born children of immigrants have been labeled many terms: “Non-English Speakers”, “Minority Language Students”, “Potentially English-Proficient Students (PEPs)”, “Limited English-Proficient Students (LEPs)”, “English as a New Language (ENLs)”, “English Language Learners (ELLs)” and Emergent Bilinguals (EB). Definitions and understanding of this type of population have evolved to consider these students’ learning more positive. Although teachers still struggle today to see them as comprehensive case studies with specific stories and needs. Pedagogical strategies transform as the increase in immigration demographics demand schools and communities to address this student population and the teaching/learning requirements. There have been two main curricular paths schools take to teach English to these second-generation speakers of other languages. The first and most popular in the U.S consists of transitional models where the goal for the learner is to become proficient in English; the second model targets dual-language learning and development of bilingualism. The latter is only implemented in areas where there are enough speakers of one language to balance classroom enrollment with half English monolinguals and the other half with a common immigrant language, which targets the entire school population to become bilingual. Tables 1 and 2 below summarize the models within transitional, maintenance or dual approaches, their goals, target populations, language literacy used and content-based language (Brisk, 1998).

| Models | Goals | Target Population | Language Literacy | Distribution Subject Matter |

| 1.ESL | ELD | Minority | In English | Content-based ESL (some programs) |

| 2.Structured immersion | ELD | Minority | In English (Some limited L1) | Sheltered English for all subjects |

| Bilingual Education Model | Goals | Target Population | Language Literacy | Distribution Subject Matter |

| 3.Dual language | Bilingualism | Majority, international | L1 and L2, or L2 and L3 | All in L1 and L2; or all in one, and some in the other |

| 4.Canadian immersion | Bilingualism | Majority | L2 first, English later (early) | All subjects in L2 for 2 years; in English and L2 remainder of schooling |

| 5.Two-way | Bilingualism | Majority, Minority | L1first for each group or L1 and L2 for both | All subjects in L1 and L2 distributed equally over the grades |

| 6.Two-way Immersion | Bilingualism | Majority, Minority | First in minority’s L1then in English | All subjects in minority’s L1first, increasing use of English over the grades until it reaches 50% |

| 7.Maintenance | Bilingualism | Minority | L1 literacy first, then in English | All subjects either in both languages or/and some subjects in native language others in English |

| 8.Transitional | ELD | Minority | L1 literacy first, then in English | Most subjects in L1with ESL instruction; gradually to all subjects in English |

| 9. Submersion with L1 support | ELD | Minority | English literacy, limited L1 literacy | All subjects in English with tutoring in L1 |

| 10. Bilingual immersion | ELD | Minority | L1 and English literacy from the beginning | Concept development in L1; sheltered English for all subjects |

| 11. Integrated Transitional Bilingual Education | Partial bilingualism, ELD | Minority with Majority participation | L1 literacy first, exposure to English from the beginning | All subjects in L1 and in English, but assignment by student suited to language needs, and particular program structure |

Strategies to Maintain Heritage Languages Regardless of the Model

Variations of models above guide teachers’ strategies to teaching. However, as technologies present us with more tools into learning content, educators must transform their practices considering multi-literacy pedagogies and this includes the practices used for teaching speakers of other languages. Literacy pedagogy has transformed as a new generation of students enter classrooms with different perspectives about reading and writing. For instructors that have experienced technological changes early in their careers, but were educated with outdated pedagogical theory, it becomes challenging to engage the “app generation” (Gardner and Davis, 2014) with traditional approaches to teaching grammar and written composition. Teaching the heritage language speakers, today, requires adapting and merging their multifaceted diversity, their experienced technological skills, language proficiencies, and funds of knowledge (Gonzalez, Moll, & Amanti, 2005) students bring into the classroom. These new approaches to teaching literacy within bilingualism must be attentive to the students’ interest in shifting their use of an oral-private language into a written-public one. For this purpose, the development of a sociolinguistic teaching methodology, where teachers prompt students to explore aspects of their own identities through oral narratives and written autobiographies in the classroom (Potowski, 2005). This becomes essential for analyzing retrospectively and reflecting about their students’ linguistic and cultural diversity, while acquiring academic literacy proficiency in their heritage language . However, this alone does not address the way that “digital natives” learn. The work of multiliteracies pedagogy (Cope and Kalantzis, 2009) reveals that it is not only about the textbook or the sociolinguistic approach to instruction, but also the development in understanding there is a multi-literate world [that digital native ]students more proficient in new media navigate with ease where the instructor is less proficient. This often detaches teachers’ more traditional, or print centered, understanding of literacy development. A teaching proposal to address linguistic diversity departs from the private reflection, personal stories that may inspire conscious re-construction of students’ bilingual – bicultural identity. Digitizing oral and written autobiographical discourses through devices beyond the pencil and paper and allowing students to code-switch, or translanguage, between their languages in digital communication as it is naturally reproduced by their bilingual proficiency, would give these students a voice in a web-connected world. One example of this process is in the Living Bilingual blog, where SUNY-Oneonta students share their stories of growing up bilingual and bicultural. Using these digital spaces to promote multilingualism will help develop global citizenship and give visibility to speech communities that have been invisible due to the influence of ideologies of the dominant culture and language (Montoya 2009). New educators’ research has suggested that if heritage speakers ought to maintain their home languages and make use of it in public domains, it may provide students with key elements to be active members in the advancement of their communities. This analysis posits how human migration affects the use of language among communities and observes how the maintenance of heritage languages is used in social networks for survival, adaptation, and conservation of an ethnic identity. (Milroy, 1980; Mines & Massey, 1985; Grim-Feinberg, 2007; Paris Pombo, 2006).