2 Towards a Philosophy of Education

Thor Gibbins

“The original Greek idea of pedagogy has associated with it the meaning of leading in the sense of accompanying the child…in such a way as to provide direction and care for his or her life.

Thus, from an etymological point of view, a pedagogue is a man or woman who stands in a caring relation to children: In the idea of leading or guiding there is a ‘taking by the hand,’ in the sense of watchful encouragements, ‘Here, take my hand!’ ‘Come, I shall show you the world. The way into the world, my world and yours. I know something about being a child, because I have been there, where you are now, I was young once…Leading means going first, and in going first, you can trust me, for I have tested the ice. I have lived. I know something of the rewards and trappings of growing towards adulthood and making a world for yourself. Although my going first is no guarantee of success for you (because the world is not without risks and dangers), in the pedagogical relationship there is a more fundamental guarantee: No matter what, I am here. And you can count on me.’”

-The Tact of Teaching: The Meaning of Pedagogical Thoughtfulness by Max van Manen

Before We Read

Carefully read the above quote by pedagogical philosopher Max van Manen. In this statement, what is van Manen’s concept of how children learn? What is the relationship between student, teacher, and the world? What is required of the teacher within this educational philosophy?

Critical Question For Consideration

As you read, consider these essential questions: What is learning? How do students learn? How do we know students have learned? What are the relationships between the construction of knowledge (learning), students, teachers, and the world, or community?

ReStorying Philosophy: An Introduction

Most chapters on philosophies of education usually start with a short overview of Western philosophy beginning with Plato and Aristotle which highly valued these two philosophers as the central figures of philosophy and are foundational to any western “civilization” grounded on idealism (Plato) and realism (Aristotle). However, this worldview is misguided and shortsighted. Rather than outline all the philosophical movements of western philosophy and connect these philosophies on the how and why of learning, this chapter decenters the typical outline. This chapter seeks to frame education from a non-western philosophy while making connections to how this different perspective might allow us to revise our own understanding of teaching and learning that has been shaped by our own internalized Eurocentric worldview. A view of learning atomized and disconnected from the material world. This is not an attempt to co-opt and romanticize a non-western perspective; it is, however, a way to help untangle an internalized worldview of learning that may help young people and the educators tasked with teaching them a more effective way at solving myriad crises that an atomized worldview of teaching and learning that is incapable of solving.

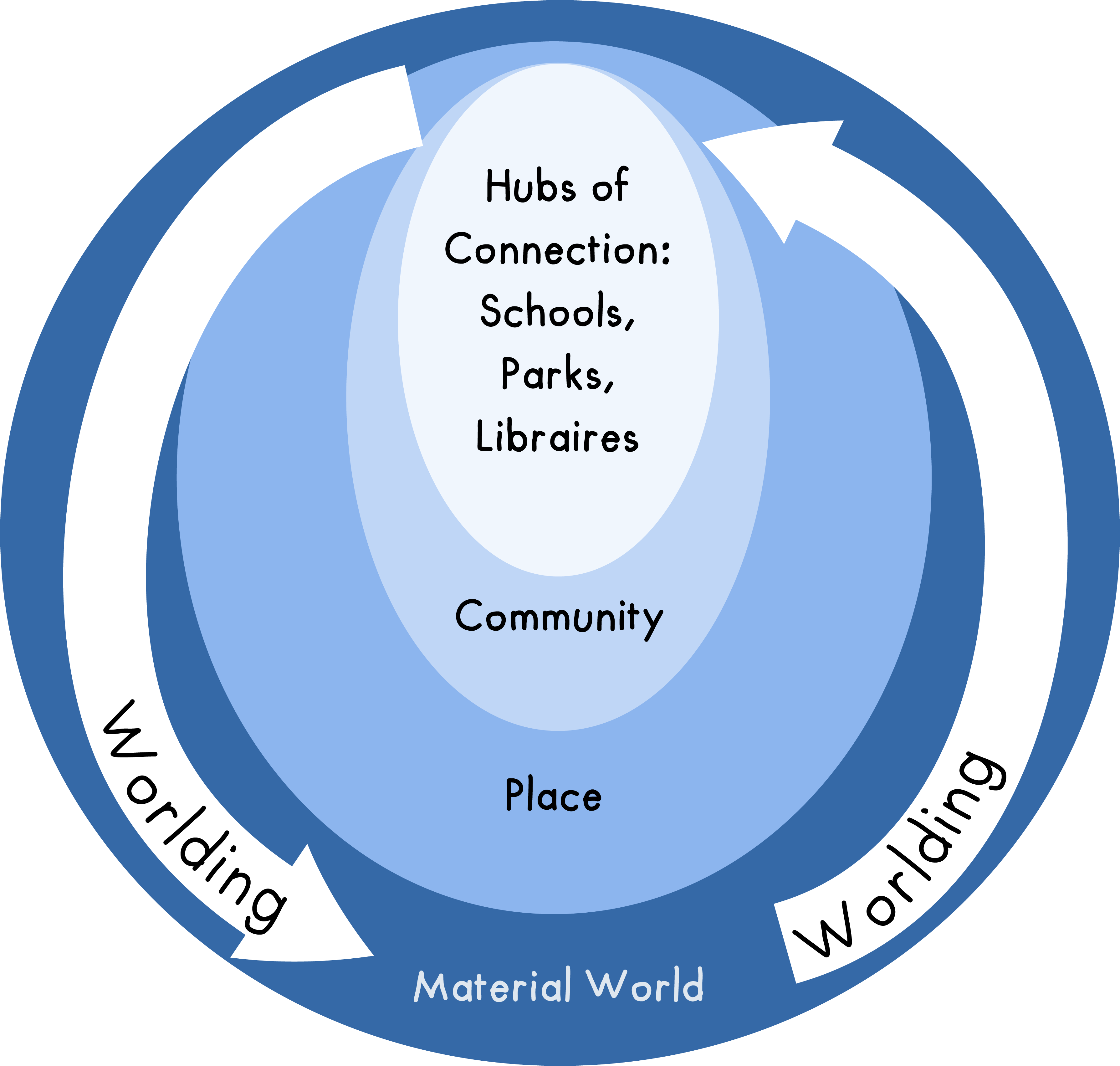

Philosophy from a Western perspective begins with the individual as the singularity; whereas, according to philosopher Viola Cordova (2007) non-western philosophies tend to proffer the world, place (Figure 2.1) in particular, as the primordial locus from which human beings emerge. There is no singular “starting” point emanating from a single individual, but, rather, a group of people–a “we”–is tethered to a particular place in the world. Because we have to breathe air, eat food, and drink water in order to survive, we cannot remove ourselves from the material world that gives us sustenance to live. Therefore, the material world and place should serve as the base for how we, as educators, develop a philosophy of education. Places and communities are what build and sustain schools. This is not limited to primarily geographic features of the place, but the social world as well. Therefore, the relationship between the ecology, economy, and social relations within the community undergird the school, teachers, staff, and students. There is a web of relationships within this connected place that should not be furcated into separate entities which isolate and remove individuals from their connected community. Embedding education within a world, a philosophy of education orients itself toward the “how” of education rather than the “what” of education: How do we (re)connect ourselves and our students to the material world where our students are no longer alienated individuals who become more isolated from each other? How might we see ourselves as a part of a greater whole, which, as Cordova points out, does not lead to a sense of ourselves as anonymous to the whole, but rather a greater sense of ourselves as responsible human beings? In this manner, “one is never anonymous.. [we] must be responsible for ourselves and to others” (p.157). This framework offers a possibility on how we, as educators, may develop a philosophy of education. This chapter restories a philosophy of education embedded in the material world consisting of diverse geographies, people, languages, communities, and public hubs connecting members of the community with each other. From this world, place, and community, this chapter moves to then connect to theoretical paradigms of education framed within the social and connected world: social constructionism and social constructivism.

Meet the Theorists

Viola Cordova was Native American philosopher who focused on the knowledge (epistemological) and language (semiotic) systems across North America in relation to the trauma of European colonization in order to reveal how Native American systems derive from place.

Discussion Activity

The central premise of Cordova’s philosophy is grounded in place. With a partner(s), have a conversation about how place and community shape the ways you talk, act, and behave. Did you ever see yourselves as a part of a larger community where you held and shared responsibility for the place and each member of the community?

Reconnecting Ourselves to the World, Place, and Community

Cordova (2007) connects her philosophical description of the world with the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis which asserts the concept of linguistic relativity where the structure of a language shapes the worldview of the group of people who share a common language. European languages are dependent on static nouns, which are fixed in relation with each other. This results in a worldview based on interpreting the world through cause and effect. For example, in English, a sentence requires a subject (a noun or noun phrase) and a predicate that can be reflexive and add meaning to the subject: “I am happy.” Or, a predicate can create a relationship between a subject (noun or noun phrase) and an object (a noun or noun phrase): “I opened the book.” In contrast, Cordova points out how the Hopi “developed a language largely dominated by verbs” (p.101) much like many other American Indigenous languages. This results in a language that shapes a worldview of continual motion and change. Cordova employs the central metaphor of wind to describe this continual motion and change where there always has been something rather than nothing:

Just as the foundational thought of Western societies is the idea that “once there was nothing and then something was brought into existence,” the indigenous Americans believe that “something” always has been and manifests into the many diverse things in the world. Each thing is, in a sense, a “part” of the greater whole. Diversity is its hallmark. (p. 104)

People, then, are embedded in a world in continual change with diverse geographical places, which share a uniquely diverse relationship with the world where “each group is seen as essential to the place in which they find themselves” (p.146). People “are not…’meaningless things’ in a ‘meaningless world. They fit in a particular place for a particular reason” (p. 146). To be unattached to the world, then, is to be alien and merely “humanoid.” If we are to develop a sense of seeing our primordial attachment to the world and place, we need to see ourselves as unique individuals as always a part of something greater– a family, a community, a place, a world. We are no longer anonymous individuals removing ourselves from place and community out of fear of ourselves becoming “‘submerged’ into an anonymous ‘mass’” (p. 147). We are emplaced and located in a larger whole–which offers us a sense of belonging. This is worlding (See figure 2.1).

A philosophy for educators, then, is to assist us in revealing our sense of belonging to a world greater than ourselves for our students. A world where our unique emplacement in geography, languages, and cultures construct diverse communities of people rather than a singularity centered on the abstract concept of human. A concept constructed by eurocentric framing which posits the “ideal” human as an abstract, platonic universal resembling a northern European male (Cordova, 2007). The essence of a connected pedagogy which reveals and worlds a sense of belonging and invites us, as educators, to comport our belonging and lead students in three determinations about the world we live in:

- First, we (teachers and students emplaced in a unique community) should learn to define and describe the world and our unique place and relationship with the world.

- Second, we should determine what it means to be human in the world as it relates to our definitions and descriptions; and, third, we should attempt to outline our role within the world.

- Third, once we develop these determinations about our relationships with our community, place, and world, we can begin to describe the constant, continual process of how we socially construct and conceptualize our world.

The Social World: Social Constructionism and Social Constructivism

The central metaphor of rugged individualism that guides how many in the United States conceptualize themselves in relation with others and the world is antithetical to the material reality of human beings according to Cordova (2007). We are social creatures who have developed socially and through community. It is very difficult for a lone individual to survive in the world without the collaboration and cooperation with others in a community. Take all those survival shows on television that showcase the enormous difficulties involving finding the essential resources to survive: food, water, shelter. Even the most skilled survivalist proficient in hunting and designing shelter has much difficulty surviving as a rugged individual for more than a few months. Moreover, the psychological toll of isolation is traumatic. We are social creatures who need each other to not only survive, but thrive within our world. As such, we develop our social languages which then construct our worldview; and thus, we socially construct our concepts, beliefs, and values as cultural artifacts within our relationship with our world, place, and community. This is the central premise of social constructionism. In addition, since we are inherently social creatures, we think and learn through our embedded relationships with others in our world, place, and community. This is the central premise of social constructivism. These two paradigms have shaped how educational theorists and philosophers conceptualize pedagogy that has been shaped over the last hundred years.

Social Constructionism: Between the Real and the Ideal

Within the philosophical spectrum that separates Western philosophy between realism on one side and idealism on the other, the central premise of social constructionism connects an objective reality separate from human beings (realism) and abstract forms and ideas existing in a non-physical, timeless universe beyond our physical reality (idealism). Like Cordova’s (2007) philosophical worldview, social constructionism positions human beings within a universe where everything we come to know and conceive about the world is interpreted through our embodied interaction with each other and the world. Unlike Cordova’s worldview, however, just as other philosophical paradigms stemming from Western philosophies, social constructionism removes the world as primordial to our lived experience and existence. Social constructionism places the singular human as the central authority that exercises agency to interpret and rule over the physical world. Social constructionism can help reveal how we socially construct our conceptual understanding of our physical reality; however, we should foreground our own embedded relationship with the world as we develop and transform our understanding of the world.

Social constructionism asserts that our conceptual understanding of the world is interpretive through language and other semiotic (meaning-making) systems and, therefore, is socially constructed. Cordova (2007) points out that before the violence and exploitation of colonialism, people identified their sense of belonging and membership within a community according to their geographic location, common language and dialect. For example, our current conceptions of race and racial categories are social constructs that have no reference to an external objective reality. For example, whiteness as a racial category did not exist as a concept until there became a social need to justify European colonialism and chattel slavery as means of extracting resources from the colonized worlds. At our primordial level as beings in a world, we recognize the humanity and sentience of other human beings, which is, at its essence, an Ethics of Care for and with another human being (Levinas,1998). Therefore, for an economic system as cruel and inhumane as colonialism and slavery to sustain itself without mass revolution and resistance, a socially constructed racial caste system is required to justify these practices. This acts as a vehicle of control by the few over the masses. Within this system, an “in-group” is constructed and becomes socially accepted as “civilized” who may have some limited access to privilege and leisure; this “in-group” construction requires a perceived Other, or “outsider,” who becomes framed as “savage” or “barbaric.” Other people are now seen as less than human by those in the “in-group.” Whiteness as a social concept continues to be redefined and constructed. For example, the Irish were not seen as “white” by the socially constructed “in-group” already marked by whiteness until the mid-20th century. Moreover, a racialized Other may receive “honorary” membership within the “in-group” within certain social circumstances. Black feminist theorist and sociologist Patricia Hill Collins (2009) recounts how she received honorary whiteness on a tour of apartheid South Africa. Collins also points out that individuals who may be initially marked white by the larger society may receive honorary Blackness. This honorary membership occurs either by explicit transgressions against “in-group” rules and norms or by growing up, living, and demonstrating solidarity within communities of color. If there was any external realism or biologically determined essence of race, these amorphous transformations of whiteness tied to specific historical and geographic contexts would not be possible.

Not only do we continually construct and reconstruct concepts like race, we also socially shape our attitudes and beliefs toward these concepts. For example, take how the media frames our perceptions of poverty and those experiencing the trauma of poverty. Rather than framing those living in poverty with empathy and care, the media (news, film, television, and social media) constructs a narrative of those living in poverty as “lazy” or “mentally ill.” Therefore, we, as a society, can justify ignoring their trauma because they “chose” to live in poverty where they continually live in constant insecurity: safety, food, and housing. If we were to see their humanity and their belonging in our community, we would then have to critically analyze an economic system that creates and depends on poverty to sustain itself. As Cordova (2007) points out, we need to develop our determined role of how to be human in our world. We cannot care for our place and community if we ignore invisible others in our place and community. The continual constructed invisibility of those living in poverty is not sustainable because it ignores the systematic structures that erode, disconnect, and alienate ourselves from our world, place, and community.

We, as educators, should critically examine our own attitudes and beliefs not only about broader social issues like poverty, but our attitudes toward content and curriculum. One example is teachers’ attitudes toward reading and writing. There is substantive research over several decades that reveal teachers’ own attitudes about reading affect their students’ own attitudes and motivation for reading (Brophy, 1986; Nathanson, Pruslow, & Levitt, 2008; Skinner & Belmont, 1993; Sweet, Guthrie, & Ng, 1998). This means that if a teacher has negative attitudes toward reading or writing, these negative attitudes will instill negative attitudes toward reading and writing in their students. Research (Aguirre & Spencer, 1999; Beswick, 2007; Borko, Peressini, Romagno, et al., 2000; Conner & Singletary, 2021) has also shown a similar phenomena in mathematics education. These studies found how math teachers’ beliefs about teaching and doing math impacted their instruction, which included the teachers’ goals and the types of teaching strategies they used. Our own attitudes toward certain content disciplines have already been shaped by our own shared experiences as students with our previous teachers and classmates. Our attitude toward the content we plan to teach has been socially constructed. Therefore, we need to critically examine these attitudes and beliefs before we can begin articulating our own philosophy on teaching and learning.

Social Constructivism

While social constructionism describes how we conceptualize and define our world through social interaction and relation, social constructivism focuses on how our own cognition through thought and language is inherently social. Seminal scholar and psychologist Lev Vygotsky developed a theory about thought and language that would evolve into how we define social constructivism as a theory of knowledge. Vygotsky (1986) asserts that our development of speech and thought (our interior monologue) does not develop from our individualized minds and move outwardly into the world; rather, the social world, which includes language and norms and rules associated from a particular culture, moves from the social world toward the individual child which manifests first as expressive speech and then becomes internalized as interior monologue known as the “ingrowth” stage. All learning, then, stems from an external social world that gradually becomes internalized by an individual child. In developing this theory of knowledge, Vygotsky posits that through this social learning action, there is a Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD), where a child is able to learn by completing a task with much support from a more experienced learner–either a teacher or peer tutor. Supportive scaffolds are gradually removed to the point where the child can complete the task independently without these supports. If a child cannot complete the task with maximum support, then that learning task is beyond the child’s ZPD and that learning task needs to be placed on hold by the teacher until the child has developed and grown to the point where the child can complete the task with assistance or support. ZPD is foundational to educational learning theory and how most schools of education train teacher candidates in how to pre-assess students and plan instruction.

While teachers use ZPD in their instruction in myriad ways, one concrete example of how teachers use ZPD in classroom instruction can be seen in literacy instruction in the primary grades. A common method of instruction in early grades is Language Experience Approach (LEA). In LEA, teachers use a common, shared experience, e.g., a field trip, a book read aloud to the class, or other shared event, to lead students in writing about their shared experience. The teacher is the more experienced learner, or writer in this case, and probes student responses to help facilitate the teacher’s writing on a large anchor sheet with students typically sitting together on a reading rug. The teacher can model spelling, spacing between words, and punctuation as the students assist the teacher with retelling the story of their shared experience. The teacher is the primary support or scaffold in assisting students who may not have the discrete literacy skills to write about the experience themselves. The students, also, support each other in the retelling as well. In this scenario, the entire lesson and actors (teacher and students) collaboratively create a ZPD to help develop literacy skills in reading, writing, listening, and speaking.

Meet the Theorists

Lev Vygotsky (1886-1934) was a Russian psychologist and seminal theorist in education. His scholarship was primarily ignored and unknown in the United States until the 1960s when his work Thinking and Speech, later to be retitled Thought and Language, first became published in English and distributed outside of the Soviet Union.

Social constructivism frames learning as inherently a sociocultural interaction with an individual and culture, community, and world. The internalizing of thought and language, however, does not work as a one-way direction from the social to the world. We have agency and can exercise our agency shape and change our community and material world. The clearest example is how we shape our world through our use of tools–e.g., hammers, shovels, etc. Working from this paradigm of humans embedded in a larger sociocultural world, Vygotsky along with theories by his contemporaries Rubinstein and Leont’ev sociocultural theories of knowledge began to outline how we employ tools, including symbolic tools like language (and writing), to shape our world. Tools, including language, are foundational to social constructivist oriented pedagogies such as activity theory and dialogism.

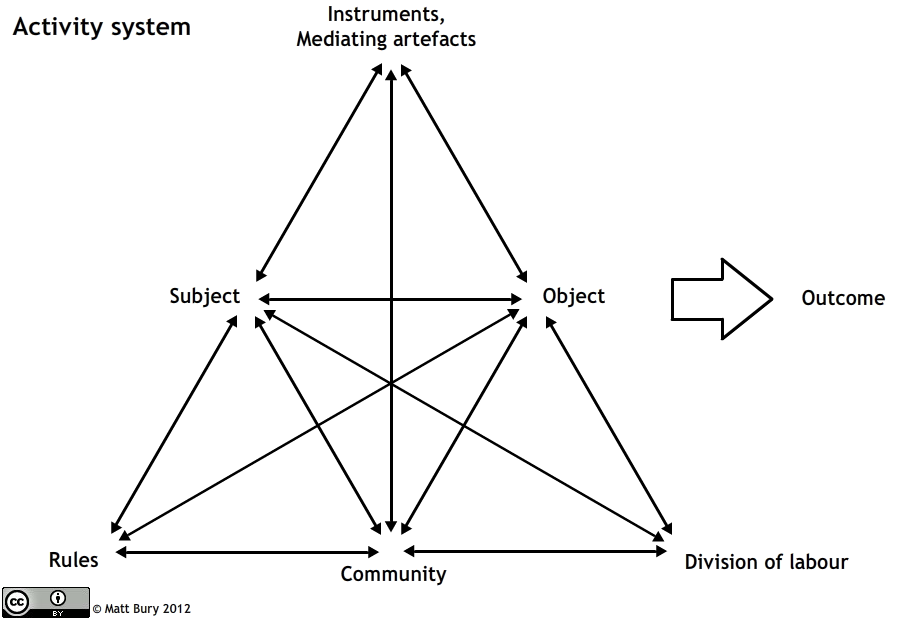

Activity theory evolved as a theory of knowledge that describes how individuals use external tools and internalized tools within a web of interaction where artifacts shape the sociocultural world. Scandinavian learning theorist Yrjö Engeström (1987) expanded on the social constructivist frameworks developed by Vygotsky, Leont’ev, and others into a broader, more comprehensive theory of knowledge. Within Engeström’s system of activities (Figure 2.2), a subject, or subjects, interact with tools or mediating artifacts, toward an object or goal that extends outward toward the world. Within this engagement, there are systemic rules, which can be scientific like the laws of physics or rules and norms determined by a larger community, that, then, affect how the subject interacts with the mediating tool or artifacts outwardly onto the world.

How might activity theory look within a classroom setting? Take the previous example of using LEA in a primary-grade literacy lesson. In the LEA example, the teacher and students work together as subjects toward an outcome of formulating a written retelling of a common experience (outcome). The object is the written draft on chart paper. The mediating tools and artifacts are the chart paper, markers, reading rug, the shared language(s) of the students and teacher, and any other mentor texts previously read or written as a class. There are rules of syntax, e.g., the rules governing how words form larger units like phrases or sentences, and genre which shape what type of writing the class drafts together. The classroom rules and norms established by the teacher and students create a community which shapes the interaction of the subjects as well as how the division of labor is distributed. In this case, the teacher takes responsibility as scribe and chief editor while the students take responsibility for the creative labor of providing the key details and important events of the retelling. Whenever we step inside a classroom, we can concretely observe and describe the teaching, learning, and knowledge building through Engeström’s Activity System.

Activities for Guiding Comprehension

- Observe a classroom lesson either in person or using an online video. Use Figure 2.2 and annotate Engeström’s Activity System. Who are the subjects? What are the objects and outcome? What are the meditating tools and artifacts? What are the rules guiding the activity? In what ways does the community (classroom) shape interaction, rules, and labor? In what ways is the labor (physical and/or creative) distributed? Share your annotation with a small group or class.

- Social constructivist theories of knowledge still remove the individual or individuals as separate from the world according to Cordova’s philosophical worldview. Create a remixed visual artifact using the worlding Figure 2.1 as an overlay. Embed Engeström’s Activity System (Figure 2.2) within the material world, place, and community. How do these systems emerge from the material world, place, and community? Annotate examples, draw and label connecting arrows to and from the systems and world layers to show the processes and transformations. Share your visual artifact with a small group or class. (Note: Instructors could model and use the ZPD by drafting a partial model of how they envision this artifact for the class. Remember, there are no correct or incorrect ways to create these visual artifacts. The learning goal is for all the learners to begin developing their own conceptual models of how philosophical worldviews shape theories of knowledge.)

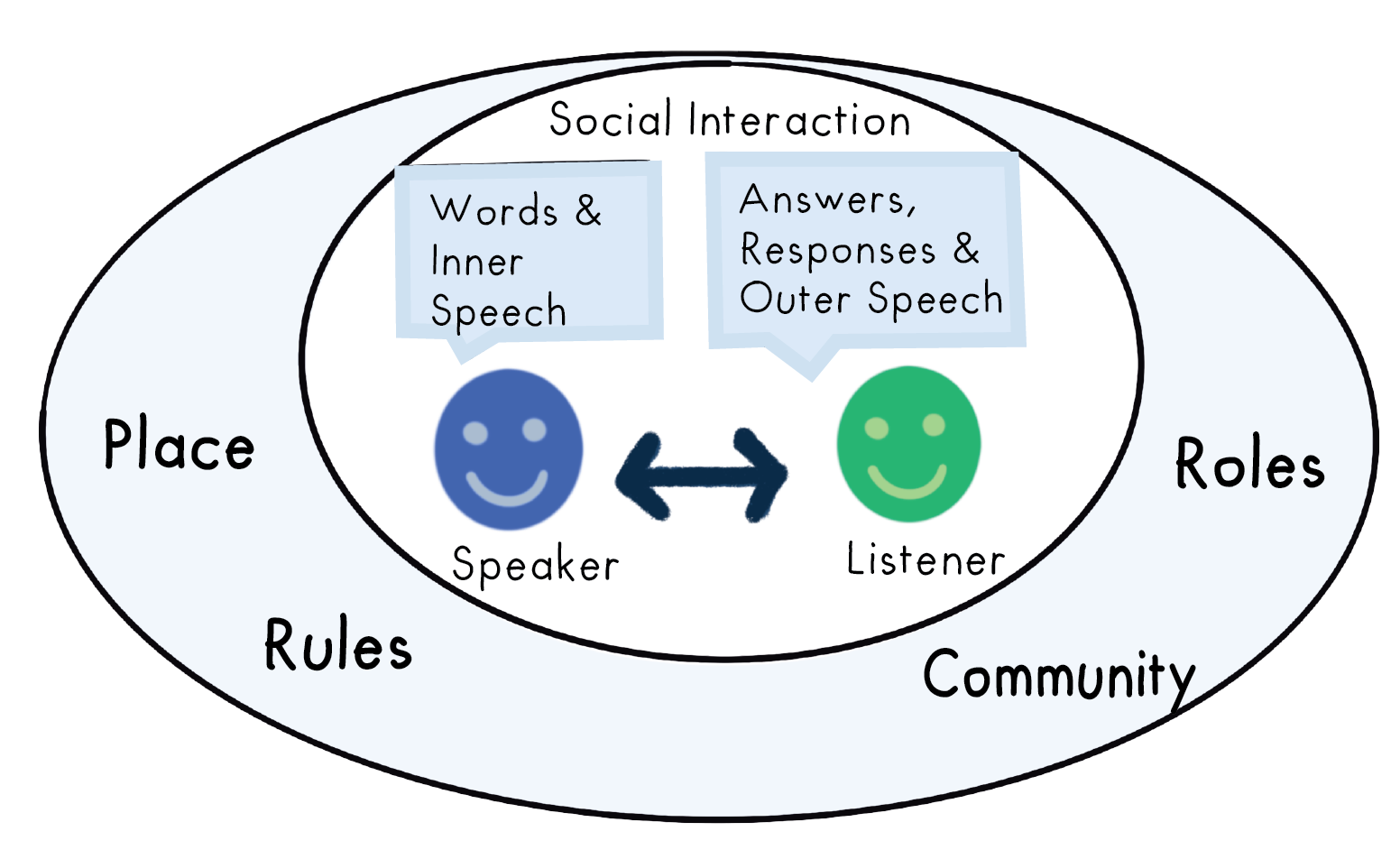

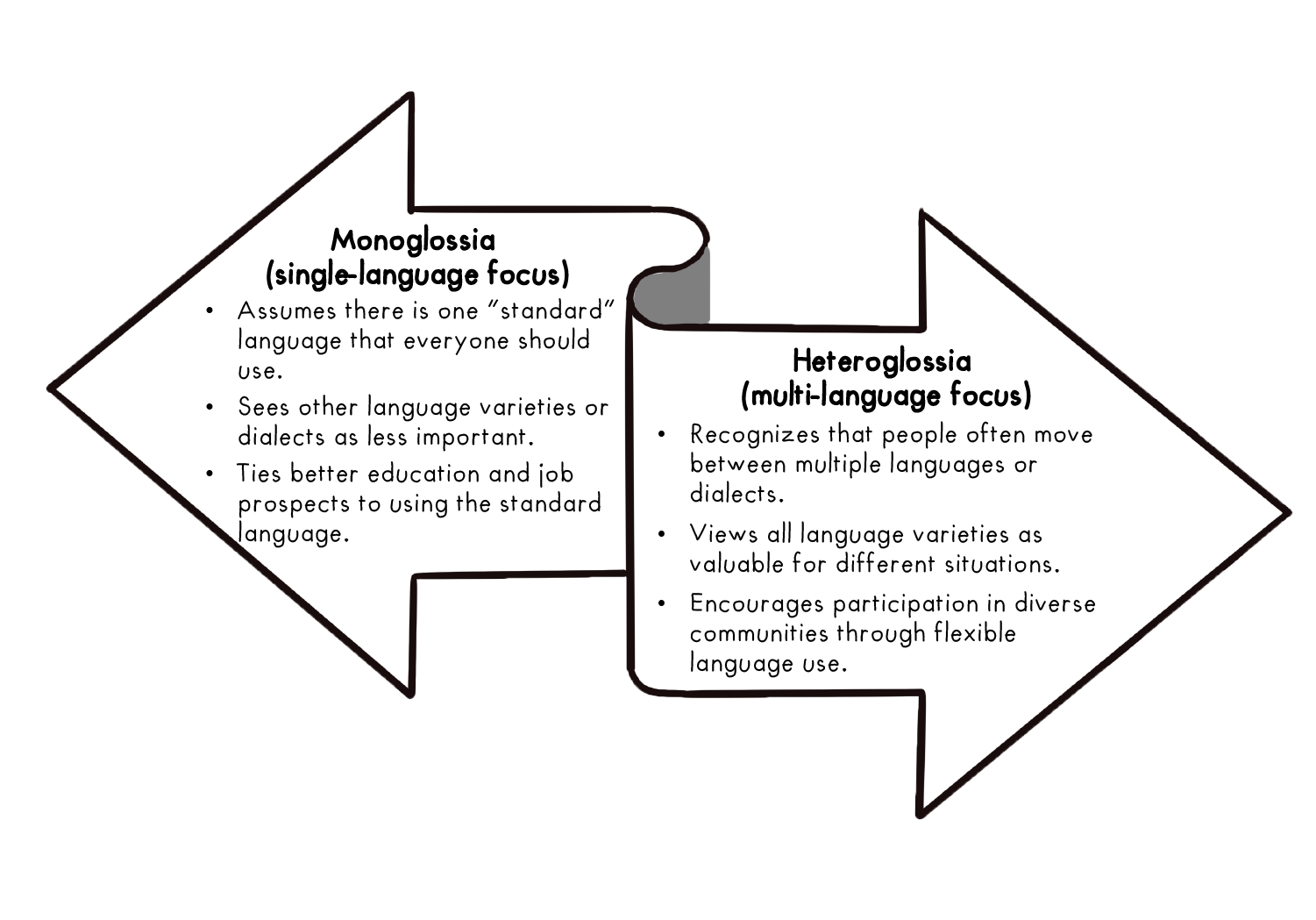

Dialogism, another theory of knowledge that emerged from the same era and place as the sociocultural theories, has had considerable impact on teaching and learning. Russian philosopher and literary theorist Mikhail Bahktin (1982) introduced dialogism, or dialogue, as inherent within language and discourse. One utterance of speech should not be reduced to a single individualized monologic utterance devoid of the social context. One single act of speech contains the historical development of the words or phrases and has transformed over time in dialogue with other speakers past and present. A single utterance–even when alone–is inherently dialogical. For Bahktin, every utterance–spoken, written, or gestural– is embedded in a socio-historical world containing a past, the present, and possible futures. The world in which discourses reverberate to make meaning are dialogic and heteroglossic. Dialogism asserts that within language and discourse, every utterance is always in a relationship with multiple voices and perspectives with unique histories and perspectives and come together in a dialogical relationship–or dialogue (Figure 2.3). Bakhtin (1984) asserts “dialogism is an almost universal phenomenon, permeating all human speech and all relationships and manifestations of human life” (p. 40). In addition to the dialogical relationship inherent in discourse, our language systems are heteroglossic in nature. Heteroglossia can be simply translated as “other-languagedness” (Vallath, 2020). What this means is that within any language, there exist traces of many different languages which have shaped the word, phrase, and denotative and connotative definition. For example, within any of the Englishes spoken around the world, there are traces of Latin, Greek, French, Spanish, German, Gaelic, and other world languages current and historical. Take, for example, the word story (narrative or tale) which contains traces of the Old French estorie that derived from Latin historia; therefore, story and history overlap and contain traces that affect each word’s meaning. Whenever we utter a word or phrase, we utter a word or phrase that has a prior sociocultural history. This utterance also invites new possibilities we can reinvent for new meanings intended for new audiences. Take, for example, how young people have reinvented terms like “brat,” “rizz” (truncated form of charisma), and “for the plot” in relation to their peers and connected youth cultures. Language and discourse is always in play; and this play is a social, collective dialogue with a past, present, and future.

In what ways might we apply dialogism in our practice as educators? One study (Cohen, 2009) on the pretend play of preschoolers describes how children appropriate and assimilate each other’s utterances in pretend play either playing alone, in parallel play, or with each other. In their play, children will adopt adult roles and discourse of their intended role. In play, children adopt roles like teachers, doctors, scientists and learn to develop their own conceptual understandings of the social knowledge and discourses these roles play in the community. Teachers can employ dialogism in their daily lessons and practices. Rather than relying on teacher-centered monologues and lectures, teachers can shape their classroom community that supports dialogical interaction with all the learners (including the teacher as the more experienced learner) in the classroom community. There are many different types of discussion activities that allow students to assimilate and appropriate academic discourses in a variety of contents and grade levels. Activities such as think-pair-share, save the last word, and ask the author incorporate dialogism where they employ social constructivism as the underlying theory of knowledge of the learning activity. We, as educators, should always be clear in how our educational philosophy connects to the real craft of teaching in our classrooms. As pre-service teachers gain more conceptual understandings of pedagogy in coursework and field experience, pre-service teachers should start noticing and connecting the different types of learning activities with different teaching philosophies.

Worlding Pedagogy: Turning Educational Philosophy into Practice

For many, philosophy tends to be esoteric and difficult to connect the abstract with our real, material world and experience. Philosophy does, however, affect how we shape the purpose of schools as well as the practice of teaching and learning in classrooms. While developing from the western tradition, pragmatism has had considerable impact in shaping teaching, learning, and curriculum in the United States. In short, pragmatism asserts that our human lived experiences tied to a real, external material world shape how we construct knowledge and form truth claims. What counts as real or true are functional in terms of how we, as human beings, go about inquiry and our investigations of the world and cannot be disconnected from our own contexts as beings in a world. The maxims of pragmatism do parallel Cordova’s (2007) non-western philosophical description of our relationship and belonging to and with the material world, place, and community. Philosopher John Dewey, whose work was grounded in pragmatism, transformed this philosophy into an educational philosophy that shaped the development of progressive education in the early 20th century. Dewey designed a laboratory school at the University of Chicago that connected this philosophy to a pedagogy of learning by doing. The University of Chicago Laboratory Schools and other laboratory schools like at the University of California at Los Angeles continue as of this day–which still connect the philosophical tradition of pragmatism with progressive and social constructivist theories of knowledge.

Critical pedagogy is another educational philosophy that explicitly connects philosophy and practice, which critical educators call praxis. Educational scholars like Paulo Friere, bell hooks, and Henry Giroux assert the primary purpose of education is liberatory in nature. Therefore, educators should allow students to engage in sustained inquiry in social, ecological, or economic issues in order for them to begin to describe the systems that create inequality, inequity, or ecological and economic harm in our communities. Once the students begin to describe these systems, they may begin to make changes to help solve these systemic problems. Critical literacy scholar Hillary Janks (2014) outlines one example of how teachers may apply critical pedagogy in their classrooms. In her commentary on application of critical literacy, Janks posits five moves teachers can move to implement critical literacy and critical pedagogy:

- Make connections between something that is going on in the world and their students’ lives, where the world can be as small as the classroom or as large as the international stage.

- Consider that students will need to know and where they can find the information.

- Explore how the problematic is instantiated in texts and practices by careful examination of design choices and people’s behavior.

- Examine who benefits and who is disadvantaged by imagining the social effects of what is going on and of its representation/s.

- Imagine possibilities for making a positive difference (p. 305).

Janks describes how she worked with young people on the issue of water conservation and the problems associated with bottled water. In this project, she described how she helped guide students by naming and describing issues of water conservation. Within this naming and description, students began to focus on the consumption of bottled water as an issue for student activism. Janks and other teachers assisted students in how to find relevant, valid, and reliable information using online databases. The students then began to critically evaluate the design choices and effects of bottled water labels and how media advertises bottled water to consumers. The students then engaged in exploring the social and environmental consequences of drinking bottled water. For the final project, students designed and produced an anti-bottled water campaign as a form of subversive media to inform the broader public about the negative social, economic, and environmental consequences of consuming bottled water. Janks’ five critical moves align considerably with Cordova’s philosophical worldview (2007) in that we should learn to describe our relationship with our place and world and outline our roles as beings in relation to our world, place, and community.

The primary focus of this chapter has been to foreground the material world (land, air, water), the geography of place, the social world of community in developing an educational philosophy. Educational philosophies guide not only the types of learning activities teachers use in our classrooms, these philosophies also guide the curriculum schools use to develop a path for teaching and learning that span the different grade levels and development of young people. Another chapter describes these different types of curriculum in greater detail. However, as educational philosophies continue to transform, educational philosophy shapes the practice and craft of teaching. A philosophy grounded in the material world, place, and community allows teachers and educational theorists a chance to world a school and classroom where teachers and students have a sense of belonging to and with their community, place, and world.

Post-Reading Activities and Consolidating Understanding

Most teachers are required to write and articulate their philosophy of education. Therefore, it is prudent that you, as early-career educators, begin to develop a clear teaching philosophy that connects to how you will practice the craft of teaching in your classrooms. Many teachers use a guiding metaphor for teaching and learning to describe their educational philosophy (e.g., “teachers are gardeners”). Recall, however, that Cordova (2007) explains how a verb-centered language like the Hopi language shapes our perceptions of the world where transformation and change foreground experience with the world; this is in contrast to languages like English which fixate on static nouns to categorize the world. Rather than developing a guiding metaphor using static nouns like “gardener” or “conductor,” use verbs that demonstrate the transformativeness of learning within a community. Write a list of as many verbs as you can that best describes the transformative nature of teaching and learning. Draw and map these verbs on to a visual that captures place, community, school, and classroom with all the members of this learning community. Prepare to share your visual in groups or with the class. (Note: A Gallery Walk activity would be an excellent activity that showcases a dialogical learning activity.)

Choose another theory of knowledge derived from a Western perspective, e.g. behaviorism (Skinner), constructivism (Piaget), psychoanalytical (Freud or Jung), etc., and analyze the absence of place, community, and school. What might explain these absences? Discuss in a small group or as a whole class.

Glossary

Activity Theory: A theory of knowledge that places a learner(s) in an interconnected relationship within a system of tools, rules, and community.

Critical Pedagogy: An orientation toward education that links the emancipatory concepts of critical theory to the teaching and learning goals for the students.

Dialogism: A theory of language and learning that posits that all words and phrases are internalized and produced in the form of dialogue with other interlocutors.

Discourse: How language is used within a particular social context. For example, words, phrases, and gestures we might use in the context of a sporting event may not be acceptable in a more formal social context like an office or school classroom.

Ethics of Care: A philosophical worldview where the concern and care for others, especially others who may be more vulnerable like children or people in need of medical treatment, is primary in relation with other beings. Philosopher of education and ethics Nel Noddings emphasizes that an ethics of Care requires we must move beyond wanting to act to help others towards acting because we must help others.

Eurocentric: a biased worldview that asserts the supremacy of philosophy, science, art, and culture that originated from Western Europe. Within this worldview, people from European descent are positioned as superior to non-Western cultures.

Idealism: Greek philosopher Plato asserted there is a transcendental of absolute and unchanging ideas that form a higher reality than the material reality of our experience. These ideas (tables, chairs, strawberries) have immutable essences within the ideal, higher reality.

Laboratory School: A K-12 public school directly connected to a teaching college or university where teachers implement innovative pedagogies for the purposes of research and improving the best practices of teaching.

Language Experience Approach: A method of teaching literacy that uses the students’ own experiences and interactions with others and the world.

Primordial: Something that is foundational or primary to existence.

Pragmatism: A philosophy that asserts language and thought are used as tools to predict, solve problems, or engage in action instead as ways to describe, represent, or mimic external reality.

Realism: Greek philosopher Aristotle asserted that the universal is embedded within the particular. Therefore, we should study the form and particulars of the things (beauty, chairs, strawberries) and their relationships as they are in reality.

Social Constructionism: A theory of knowledge that posits that all concepts and ideas are socially constructed and cannot be distilled that separates the material concepts and ideas in an external reality from the social world of language and human interaction.

Social Constructivism: A theory of knowledge that asserts the social world shapes how an individual’s cognition.

Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis: A theory of linguistic relativity where the structure of language influences the speakers’ cognition and perception of the world. The 2016 Oscar-nominated science-fiction film Arrival showcases this theory as its central premise.

Worlding: A term created from filmmaker and phenomenologist Terence Malik to indicate that we (human beings) are intrinsically embedded with each other and place. This verb form of world is to emphasize the process of the ways humans construct meaning with and in a reality with others and thus, worlds become revealed. These worlds are unique to a particular place, community, and time.

Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD): For every new skill, concept, or procedure brought to task upon the learner, there is a zone where the learner can first apply the skill, the concept, or procedure with maximum support from a more experienced learner. As the learner practices the skill, concept, or procedure over time the level of support is gradually reduced. This is done until the learner is able to complete the task independently without support or assistance from a more experienced learner.

Figures

Viola Cordova by Natalie Frank is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Worlding Diagram by Olivia MacGiffert is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Lev Vygotsky by Natalie Frank is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Activity System by Matt Bury is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Dialogism by Olivia MacGiffert is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Perspectives on Language by Oliva MacGiffert is shared with a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

References

Aguirre, J., & Speer, N. M. (1999). Examining the relationship between beliefs and goals in teacher practice. The Journal of Mathematical Behavior, 18(3), 327–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0732-3123(99)00034-6

Bakhtin, M. M. (1982). The dialogic imagination: Four essays. The University of Texas Press.

Bakhtin, M. M. (1984). Problems of Dosteovsky’s poetics. University of Minnesota Press.

Beswick, K. (2007). Teachers’ beliefs that matter in secondary mathematics classrooms. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 65(1), 95–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-006-9035-3

Borko, H., Peressini, D., Romagnano, L., Knuth, E., Willis-Yorker, C., Wooley, C., Hovermill, J., & Masarik, K. (2000). Teacher education does matter: A situative view of learning to teach secondary mathematics. Educational Psychologist, 35(3), 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3503_5

Brophy, J. (1986). Teacher influences on student achievement. American Psychologist, 75, 631-661.

Conner, A., & Singletary, L. M. (2021). Teacher Support for Argumentation: An Examination of Beliefs and Practice. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 52(2), 213–247. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc-2020-0250

Cohen., L. E. (2009). The heteroglossic world of preschoolers’ pretend play. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 10 (4).

Collins, P. H. (2009). Another kind of public education: Race, schools, the media, and democratic possibilities. Beacon Press.

Cordova, V. F. (2007). How it is? The Native American philosophy of V. F. Cordova. The University of Arizona Press.

Engeström, Y. (1987). Learning by expanding: an activity-theoretical approach to developmental research. Orienta-Konsultit.

Janks, H. (2014). Critical literacy’s ongoing importance for education. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 57(5).

Levinas, E. (1998). Otherwise than being: Or beyond essence. Duquesne University Press.

Nathanson, S., Pruslow, J., & Levitt, R. (2008) The reading habits and literacy attitudes of inservice and prospective teachers: Results of a questionnaire survey. Journal of Teacher Education, 59 (1), 313-321.

Skinner, E. A., & Belmont, M. J. (1993). Motivation in the classroom: Reciprocal effects of teacher behavior and student engagement across the school year. Journal of Educational Psychology, 85, 571-581.

Sweet, A. P., Guthrie, J. T., & Ng, M. M. (1998). Teacher perceptions and student reading motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 210-223.

Vallath, K. [Vallath by Dr. Kalyani Vallath]. (2020, July 3). Bakhtin’s polyphony, dialogism, heteroglossia. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WR_6muVQFjg

Vygotsky, L. (1986). Thought and language. The MIT Press.