10 What Can U.S. Educators and Schools Learn from Finland?

Ann Fradkin-Hayslip

Before You Read

Before reading, spend some time thinking about how teachers teach. Some profess that teachers teach the way they were taught. It has also been postulated that college faculty teach not only the way they were taught but that their teaching is influenced by past experiences (Hora, 2013). In The Making of a College, a blueprint for the inception of Hampshire College, Longsworth and Patterson, propose a school that includes The Idea of the Student as Teacher. This philosophy encourages students to act as teachers, such as leading discussions and seminars, and forming collegial relationships between faculty and students. It recognizes that both teachers and learners may switch between those roles. It is about absolving the rigidity of teacher and student roles and recognizing that all of us can be teachers or learners throughout our lives (Longsworth, 1966).

Critical Question For Consideration

As you read, consider these essential questions: In what ways can the United States adopt practices from Finland to improve teacher preparation and schooling for its students? In what ways does equity impact teachers and students? In what ways does teacher autonomy impact learning and teaching? In what ways do the pedagogical and philosophical differences between schooling in the United States compare with those in Finland?

Introduction: Why Finland?

Walk into any school in Finland and obvious differences from U.S. schools will be immediately recognized. The density of parked bicycles near the entrance may be your first indicator. Depending on the size of the school, you may see hundreds of two and three-wheelers. This is because students in Finland walk or ride bikes to school. There are no school buses in the country, unlike in the United States, where thirty-eight percent of students ride a school bus. In the United States, students typically qualify for bus transportation if their designated school is two or more miles from their residence. Neighborhood schools in Finland are within three miles of most students’ homes and the commute is viewed as safe and an essential part of being outdoors (Pietarinen, 2009). Rarely do parents in Finland drive their children to school, as compared to the fifty-four percent of parents who do so in the U.S. (New York School Bus Contractors Association, n.d.). Even the youngest of children walk or bike throughout the school year, including the winter months when the temperatures may dip below freezing, and the absence of sunlight lasts for months.

Finland is a small country that espouses an education system steeped in equity, teacher autonomy, and quality education. Named the “happiest nation in the world,” it is a country that personifies not euphoria, but rather contentment. Its model of learning and teaching supports a belief that teaching is not a one-way street, that learning occurs when equity, respect, and meaning are paramount, and that education extends beyond the physical confines of a building. Finland is a model for the rest of the world.

The next notable difference may be the hundreds of shoes arranged within the school vestibule or outside classrooms. Teachers, students, and visitors remove their shoes upon entering any school in Finland. This practice is two-fold. It eliminates debris from the outside and fosters coziness. No-shoe classrooms and hallways encourage students to sit on the floor to collaborate with peers or to engage in projects. The practice also gives the school an inviting feeling. Teachers and students can be seen barefooted, in stocking feet, or clad in indoor shoes or slippers.

Other differences may depend on the size or location of the school or the population of students. Funding is equitable among all schools in Finland and members of each school may decide how that money is spent. An emphasis on physical comfort and community extends to social interaction for members of the school. Pool tables, video consoles, and rooms for students to lounge, visit with peers, or play board games is a common sight. For teachers, that sense of community can be felt in rooms outfitted with comfortable couches and chairs. The smell of brewing coffee is commonplace and encourages a collaborative and relaxed environment. The minimalistic design sets the mood for a peaceful aura. Warm paint tones and uncluttered walls contrast the institutionalized colors and often poster-plastered walls of American schools. Perhaps the most contrasting element is the absence of jarring announcements, blaring bells, hall passes, and in general, an authoritative, penal design. There is a calmness that permeates the buildings, and yet, an environment that is alive with activity.

Regardless of where schools are located, or the populations they serve, all schools are equitable. Local autonomy determines curriculum, teacher autonomy is paramount, and parents trust their children’s teachers. In recent years, Finland has become synonymous with high-quality education. This was not always the case. Decades earlier, the country lagged behind its counterparts in terms of teacher training preparedness and student outcomes. The transformation that took place in the 1990s unwittingly propelled the country into the world spotlight. Unbeknownst to the collaborators, their plan worked; not only for their relatively small nation but as a model for the world to follow.

PISA – Finland Rankings and Transformations – For Better or Worse

Much has been written about educational reform in Finland; its rising PISA ((Program for International Student Assessment) rankings, and most recently, its descent. PISA is an international organization that every three years assesses fifteen-year-old students in the areas of reading, mathematics, and science literacy. The program, overseen by the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development), began in 2000, and tests for competencies toward the end of the compulsory schooling for students (Overview, n.d.). In 2000, 32 countries participated. By 2018, that number had grown to 79, with a projected participation of 90 countries by 2025 (The Irish Journal of Education, 2023). Due to the COVID pandemic, the 2021 testing date was moved to 2022, thereby moving the 2025 date up one year (PISA Scores By Country, 2023). Since 2000, and the inception of the first PISA, Finland has ranked in the top tiers of reading, mathematics, and science literacy, although scores did decline in 2015 and 2018 (National Center on Education and the Economy, 2023). Has educational attainment declined, or rather, reached a stable point? Do international scores adequately define the worth of an educational system, or do other factors more realistically offer an unbiased view? The Finnish PISA scores from 2000 to 2022, have consistently outperformed the United States; but first, let us step back several decades to trace how this tiny country propelled its name into the news and became a model for educators around the globe.

| Year | Number Countries | Finland Reading Score (Rank) | U.S. Reading Score (Rank) | Finland Math Score (Rank) | U.S. Math Score (Rank) | Finland Science Score (Rank) | U.S. Science Score (Rank) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 43 | 546 (#1) | 504 (#15) | 536 (#4) | 493 (#19) | 538 (#3) | 499 (#14) |

| 2003 | 41 | 543 (#1) | 495 (#20) | 544 (#1) | 483 (#24) | 548 (#1) | |

| 2006 | 57 | (#2) | 504 (#) | 548 (#1) | 474 (#25) | 563 (#1) | 489 (#21) |

| 2009 | 75 | 536 (#3) | 500 (#17) | 541 (#6) | 487 (#30) | 554 (#2) | 502 (#23) |

| 2012 | 65 | 524 (#6) | 498 (#24) | 519 (#12) | 481 (#36) | 545 (#5) | 497 (#28) |

| 2015 | 73 | 526 (#4) | 497 (#24) | 511 (#13) | 470 (#40) | 531 (#5) | 496 (#25) |

| 2018 | 79 | 520 | 505 | 507 | 478 | 522 | 502 |

Historical Context – How Finland Became Synonymous with Quality Education

Throughout the late 1970s, students in the small Nordic country of Finland routinely scored near the bottom of the rankings by the OECD. A decade later, the Ministry of Education adopted a common curriculum (National Center on Education and the Economy, 2023). Finnish students began to earn average scores on international assessments, with slightly higher scores in reading (Sahlberg, Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland?, 2011). Still, the scores were not stellar, and no one was taking notice. Then, during the 1990s, a revamping of the curriculum produced a national design focused on a less-is-more approach. This undertaking pared the objectives for each grade, from lengthy pages to concise attributes for student learning. With an emphasis on learning, rather than teaching, educators strove to delve deeper into fewer concepts and focus on encouraging critical thinking and problem-solving skills. The plan also included elevating the teaching profession and by extension, granting teachers the autonomy to make their own choices about what and how they would teach and assess. The transformation that took place in the 1990s unwittingly propelled the country into the world spotlight. Unbeknownst to the collaborators, their plan had worked; not only for their relatively small nation but as a model for the industrialized world to follow. The rankings soared; with Finnish students outscoring their peers in reading, mathematics, and science literacy. Thrust into the world spotlight, educators around the globe wanted to know their secret. How did Finland become the forerunner for academic achievement? What was even more remarkable was that Finnish students and teachers spent less time in the classroom than most others, most notably, Americans. Homework is minimal, if at all, and standardized tests are practically non-existent. Yet, despite these differences, the scores outranked the other nations. Finnish educators widely speculated that there might be a scoring error, but indeed, this was not the case. What was soon realized was that there were no magical or extreme measures that predicted these results. Instead, a coming together of creating a national curriculum, respecting the rights of individual schools to amend this curriculum, a less-is-more attitude, a healthy respect for all learners, trust in and autonomy for teachers, and a balance between life and school was the prescription that healed a floundering educational system.

Pedagogical Framework

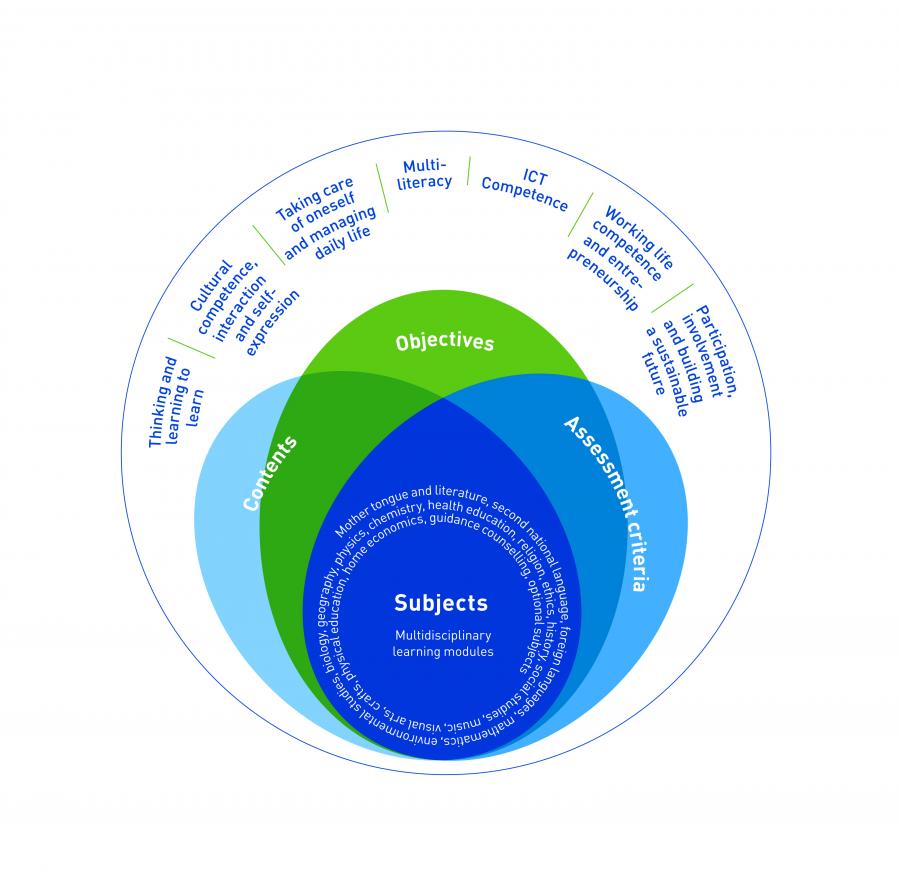

The framework of the National Curriculum is built on a commitment to ensure that all Finnish students will have “the knowledge and skills” to “remain strong in the future, both nationally and internationally.” Student-centered, the fabric of the plan is to encourage students’ “interest in and motivation for learning” (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2023). It is a structure intended.

“to enable a reform of school culture and school pedagogy which will improve the quality of the learning process and enhance learning outcomes” (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2023).

This design supports active participation by learners, to intersect knowledge and feelings, with goals and problem-solving skills. Schools are publicly funded, follow a national curriculum, and support a play-based ideology. Teachers are viewed as instructors who facilitate these aims and encourage life-long learning.

Curriculum

The curriculum in Finland is rooted in a pedagogy that supports the belief that student-centered and collaborative learning will benefit all learners (Council for Creative Education, n.d.). Regardless of the locations or populations of the schools, all are equitable, and local autonomy enables schools the latitude to adapt the national curriculum to their situations. Unlike the United States, where the emphasis is on teaching, testing, and accountability, in Finland, the focus is on learning, and an ideology that students and schools do not need to be compared to each other. This contrasts with the standards-based curriculum that currently exists in the United States. The notion of an accountability report for all U.S. public schools led to standards-based educational benchmarks for all schools. The premise was for each grade level to articulate the skills and knowledge expected of all students after the school year with the goal of teachers and schools helping students attain these criteria (Alex Spurrier, 2020). At its inception, some professed the system to be equitable and a means to identify lower-performing schools. The latter would enable educators and policymakers to find inducements or enforcement to improve these lower-performing schools. Criticism of the approach points to teaching to the test; a method to teach strategies to pass a test. Time is spent on “using the test in instruction so that the students will have encountered all of the test items before the actual test” (Top Education Degrees, 2023). Opponents argue that the time spent to prepare, take, and remediate after testing would be better spent on engaged learning activities. Currently, thirty-eight states require a standards-based curriculum, and an additional twelve states recommend its adoption (BALLOTPEDIA, 2023). In Finland, learning is fluid, asset-based, and free of threats about not measuring up.

Compulsory Education

Every child in Finland who is a permanent resident between the ages of six and sixteen is required to attend public or private school, both of which are at no cost to families (Ahonen, 2023). Learning materials, school meals, and health services are also provided free of charge (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2023). Although a national curriculum includes learning objectives and core contents for each grade, schools, and teachers are encouraged to create or adapt the framework (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2023). They may also choose how the curriculum is to be implemented and how teaching and learning will occur. The educational framework is designed to encourage and support learning from birth through adulthood. Although early childhood education is not compulsory, it is an integral part of the structure. This is followed by a year of pre-primary education for six-year-olds, and basic education for those between the ages of seven and sixteen.

Early Childhood Education and Care

The Early Childhood Education and Care Program (ECEC) in Finland serves children between zero and six years old. Overseen by the Ministry of Education and Culture it supports the belief that all children have the right to quality early childhood care and that parents have the right to choose if and how they will participate in the program(Starting Stong IV Early Childhood Education and Care Data Country Note, 2016). Parents choose whether to stay home with their infant, hire in-home care, or place the child in a public or private early childhood daycare center. If they opt to stay home, one, or both parents may take a leave of absence from their job with a combined total of 320 days of leave coverage. Monetary compensation is also provided. If parents choose a daycare center, ECEC supplements the costs. Family income determines their financial contribution, at a maximum of 300 euros, or approximately $321.18 a month (City of Helsinki, n.d.). Compared to early childhood centers in the United States, the average cost for early childhood care is $1, 230 a month, or approximately $15,000 a year. The flexibility of the Educare Model supports parents to make choices in the best interest of their children. It also prescribes the ideology that children can learn from everyday activities, whether in the home or at a center. Young children learn by serving themselves lunch or putting on their boots. This ideology also encourages independence and fosters a sense of accomplishment. Learning is viewed as joyful, and children are free to develop at their own pace. All early childhood teachers have a bachelor’s degree. The teacher-student ratio for the ECEC system is 10 children per teacher. For children under the age of 3, the ratio is 1:3, while for ages 3 to 5 the ratio is 1:8 (Starting Strong IV Early Childhood Education and Care Data Country Note, 2016). By comparison, in the United States, the average ratio is 15.3 students per teacher in kindergarten; with some states employing a 20:1 ratio (State K-3 Policies, 2020).

Play

Embedded in early childhood philosophy is the belief that play is essential for developing minds and bodies. This includes romps outside, communing with nature, overnight trips, even for three and four-year-olds, and breaks to interact with peers. Play-based learning is child-initiated and child-centered. It is open-ended and taps into their natural curiosity and interest in the world around them. Play is not a fun project that a teacher introduces, nor is it a planned, adult-led activity. “Play is the answer to how anything new comes about (Brainy Quote, 2023).” Play contributes to cognitive and social-emotional development as children learn and interact with others. Language and literacy skills are enhanced, confidence and cooperative skills, and physical development are outcomes of play-based learning.

Pre-Primary Education

Learning through playful activities and experiences extends to the pre-primary education year.

At age six, students enter the pre-primary education step, aimed toward providing them with greater opportunities for learning and development. Pre-primary education plays an important part in the continuum spanning from early childhood education and care to primary and lower secondary education. It introduces students to mathematical and reading skills without direct instruction. Instead, learners may play and explore with manipulatives, books, games, and other interactive materials. This year of exploration is designed to prepare youngsters for the following year. Childhood is meant to be stress-free; therefore, students are not pressured to acquire academic skills at a set time. Each child is viewed as an individual. Before 2015, pre-primary education was optional, however, in August of that year, The Ministry of Education mandated the program for all children. The National Core Curriculum for Pre-Primary Education, approved by the Finnish National Agency for Education, guides the planning of the content of pre-primary education and a framework for local curricula (European Commission, 2023). The four-hour day is spent on play-based and interactive activities designed to prepare young children for the subsequent school year. It is typical to observe children working cooperatively as they complete puzzles, engage in vocabulary and number-matching games, and do daily outdoor play. The emphasis is on hands-on, learning-by-doing experiences (European Commission, 2023).

Basic Education

Basic education commences after the pre-primary year, at the age of seven, and extends until sixteen years of age. It is divided into primary and lower secondary education levels. The Basic Education step, like the pre-primary year, is built on a belief that learning should occur within positive environments. One way to achieve this is the relatively short school days. Finnish students spend approximately five hours a day in school, compared to the six to eight hours American students spend in class. To balance the school day, students are given multiple breaks throughout the school day. For every forty-five minutes of class time, students are given a fifteen-minute break, and like play-based learning, this break is student-determined; not teacher-initiated. Students may play a game of pool or video games, depending on the furnishings of their school, or they may sit and visit with friends. The time is unstructured and designed to balance work with free time. Another means of a positive environment is the non-existent or limited homework assigned in Finnish schools. Homework that is assigned typically has a practical intent. It may include planning and preparing dinner for the family as an extension to a home economics class. The Finnish belief is that learners should be given the time and choice after school to pursue sports, hobbies, or interactions with others. This is contrary to the average U.S. student who may spend hours each day completing required homework assignments (Education in Finland, n.d.). When learners reach the age of sixteen, they have the option to add an extra year to their education plan. They also have the choice to pursue an upper secondary general education or vocational education curriculum. The first requires certain examinations and is aligned with preparation to enter a bachelor’s degree program. The second requires vocational qualifications in preparation for a technical degree.

Assessment

Ironically, despite the consistently high rankings of Finnish students, the educational framework is a system adverse to assessments. Assessment in Finnish schools can be defined as a system of flexible accountability (Education reform in Finland and the comprehensive school system, 2019). This practice allows teachers to determine how and when to assess their students. Self and peer assessments are common in Finnish classrooms. These methods support self-reflection and constructive feedback, according to the premise that they contribute to a n support life-long learning. There are no mandatory standardized tests for schools and although national tests exist, they too, are voluntary (Education reform in Finland and the comprehensive school system, 2019).

Core subjects for basic education include national and secondary languages, sciences, social studies, arts, technology, mathematics, religion, ethics, and home economics. Disciplines are continually updated to reflect current and best practices, and students are given choices within these disciplines. Multidisciplinary and cross-disciplinary learning often occurs as students learn skills and develop dispositions across multiple disciplines.

Transversal Competencies are also included within the education framework. Defined as emotional intelligence and experience, these skills are not associated with a specific discipline, but instead reflect the skills required to effectively navigate in the work environment. Sometimes referred to as soft skills, these competencies can include “critical and innovative thinking, interpersonal skills, global citizenship, and physical and psychological health (Heron, 2019).” At its core, transversal competencies include creativity, collaboration, conflict resolution, communication skills, teamwork, critical thinking, and media and information literacy skills (National Initiative for School Heads’ and Teachers’ Hollistic Advancement). Transversal competencies are designed to prepare learners for the future and for those jobs that have yet to be created or idealized.

Outdoor Education

Education outside the classroom (EOC) refers to curricula that take place outside the classroom (Jarvinen-Taubert, 2022). Learning may occur in a structure, such as a library, museum, or forest. Finnish culture revolves around a healthy respect and interaction with nature and schools are included in this relationship. Embodied within the country’s educational pedagogical framework, it is a given that schools support “learning, interaction, participation, well-being, and a sustainable way of living” (Finnish National Agency for Education, 2023). Outdoor education is essential, beginning with outdoor play in the ECEC program and spanning until the culmination of the basic education year. Communing with nature is regarded as an interdisciplinary approach that promotes cognitive skills and places value on individuals and the environment. Its social-emotional impact includes inquiry-based learning for the student overseeing the process and the teacher acting as facilitator (Finnish student teachers’ ideas of outdoor learning, 2021).

Everyman’s Right

The emphasis on nature stems from Finnish culture. Everyman’s Right is a decree that establishes “the right of every person to use nature regardless of who owns or controls the land” (Finnish Environment Institute, 2023). It is, therefore, not necessary to have permission from a landowner to use said property. Finland is propagated with thousands of wilderness huts and shelters across the nation. Structures range from simple lean-tos to shelters that house bunks and cooking apparatus (GONE71, 2020). Expectations are that users will respect and not alter nature and comply with rules such as staying on marked trails, camping where allowed, preserving water sources, guarding against potential forest fires, and not littering. These structures may serve as the backdrop for daily visits by school children, or for overnight experiences for children as young as three years old. This healthy interaction between school and nature brings learning to real-world contexts including “mathematics, physics, languages, art, physical education, etc.” (Jarvinen-Taubert, 2022).

Equity

The equity inherent in the everyman’s right is reflected in Finland’s education system. Every student in Finland is afforded an equitable education that spans from birth to the university level; and every student has a right to educational support (Ahonen, 2023). Children enter school with varying life situations and the dynamics of their home affect what they see and experience and impact their readiness to learn. Children who positively engage in dialogue and play at home have “higher literacy skills, better peer interactions, fewer behavior problems, and greater motivation and persistence during learning activities” (Families Are the Heart of School Readiness, n.d.). Acknowledging these variances propelled the Ministry to adopt “the equal opportunity principle …” that “…insisted that all students be offered a fair chance to be successful and enjoy learning“ (Sahlberg, Finnish Lessons 2.0 What can the world learn from educational change in Finland?, 2015, p. 28). This commitment to equity is not synonymous with equality. Rather than every student being taught the same thing in the same way, learning and teaching would now take the individual into account; however, the overarching similar component would be that all students receive a high-quality education. “People sometimes incorrectly assume that equity in education means all students should be taught the same curriculum or should achieve the same learning outcomes in school… Rather, equity in education means that all students must have access to high-quality education, regardless of where they live, who their parents might be or what school they attend” (Sahlberg, Finnish Lessons 2.0 What can the world learn from educational change in Finland?, 2015). This equity underscores the belief that all students can and should receive the preparation for higher education or a career path (European Commission, 2023). As the familiar cartoon below depicts, equality means that everyone receives the same while equity means everyone receives what they need. The added image of justice addresses the removal of systemic barriers; thus, eliminating many of the resulting needed supports.

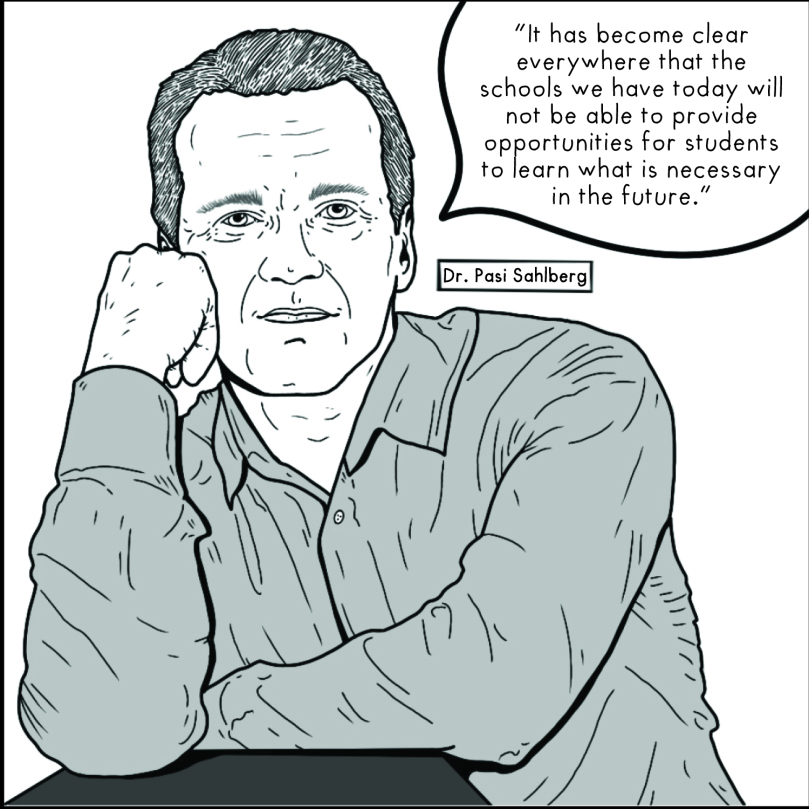

Meet the Theorist

Pasi Sahlberg (1959 – ) is a Finnish education scholar. His work explores Finnish education systems, educational reform, and education policy. He is a Professor of Educational Leadership at the University of Melbourne, Australia.

Special Education

Special education in Finland is also rooted in a philosophy of equity and inclusivity. The term special needs does not exist in the Finnish educational legislation. The belief is that inclusivity is best for learning and social well-being and that learning together benefits all students (Schools, 2022). Infused within the schools, special education support is viewed not as a negative or a distractor, but as assistance to students and teachers. Approximately 30 percent of all students receive special help (Hancock, 2011). Special education services for Finnish students are mostly focused on reading, writing, and mathematics, with an emphasis on teaching and learning rather than on a deficit mentality. In Finland, early identification is key to the prevention of learning difficulties and so more children are identified at younger ages. Compared to children in the United States, special education is defined as a disability that may entail physical, cognitive, linguistic, or other developmental delays (U.S. Department of Education, 2017). Parental permission for special education services is not required in Finland. This enables specialists and teachers to provide support as needed and as quickly as possible, unlike in the United States, where parental or guardian permission is required and where one academic year can elapse between the time a student is potentially identified, and the time services are rendered. In compliance with the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA), an initial evaluation must occur within 60 days of the request (Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services, 2017). In 2004, the reauthorization of IDEA introduced the Response to intervention (RTI) method to identify students. The three-tiered system monitors the progress of a student as interventions are intensified. Tier 1 represents approximately 80 percent of referred students, with Tier 2 and 3 representing approximately 15 and 5 percent respectively (Wiley University Services, 2013). Tier 2 may extend for eight weeks or longer. If progress is not satisfactory, further testing may be initialized. Legally, schools must evaluate students when there is reason to believe that a disability exists and need for special education services (Martin, n.d.). Months of progress monitoring, scheduled meetings, and other procedures can often mean that an identified student receives special education services toward the end of the current or at the start of their subsequent school year, unlike in Finland, where services can be immediate.

Finland also has a tier system of services; however, it differs considerably from the US model. General support refers to the strategies the teacher may provide to all students in the class. These adaptations may include flexible seating, guided practice, and differentiation strategies. Intensified support is when the teacher makes adaptations for individual students. These plans may be in consultation with the parents and or special education teachers. The third tier, special support, is for students who have a “severe disability, illness or developmental disorder” (Finland’s Approach to Special Needs & Inclusion, 2022). Even with the most severe needs, the goal is to keep all students in the mainstream classroom, and for all students to interact in and out of the classroom.

No Dead Ends – No Tracking

Tracking, the practice of placing students in classes based on ability, I.Q., or achievement (National Association of Secondary School Principals, 2023), does not exist in Finland. Initiated in the United States in the 1930’s, the practice places students on tracks, to “provide them with a level of curriculum and instruction that is appropriate to their needs” (National Association of Secondary School Principals, 2023). During the late 1960s and early 1970s, students were often tracked for either college-bound or vocational training. This meant that all their school courses propelled them on a trajectory toward college preparation, or lack thereof. In the 1970s, tracking evolved to placement for individual courses (The Brookings Institution, 2013). Students may be deemed to be on a college preparatory trajectory, thereby given a curriculum that includes requisite courses for college admission. Other students may be identified and tracked for a general education, on a path for a trade or job placement. Their track may be classified as general education with basic-level courses. A high school graduate who completed a general education track program might lack the (pre)requisites for college admission. They may then have to play catch-up, take the necessary courses of study after graduation, or accept a vocational path in life. This in no way implies that one path supersedes another or that one is better than the other. Instead, it calls into question how educators can predict an educational track for a pre-teen that may impose serious consequences on their pursuit of higher education and career options. That a track is based on judgments about perceived abilities and future trajectories is nothing short of alarming. Even with the modification of tracking being course-specific, students may still be denied entry to college if they have not taken the requisite secondary courses. Critics of tracking have also long argued that groupings often reflect SES (socio-economic status), with those at the lower SES levels tracked for vocational training and those at the higher SES levels tracked for college preparedness. Not surprisingly, tracking has come under fire for the past 20 years as being biased against low-income and minority students (The Brookings Institution, 2013). By contrast, in 1985, Finland abolished ability-level and tracking practices. Students were homogeneously grouped with the rationale that grouping students by ability amounted to inequitable practices.

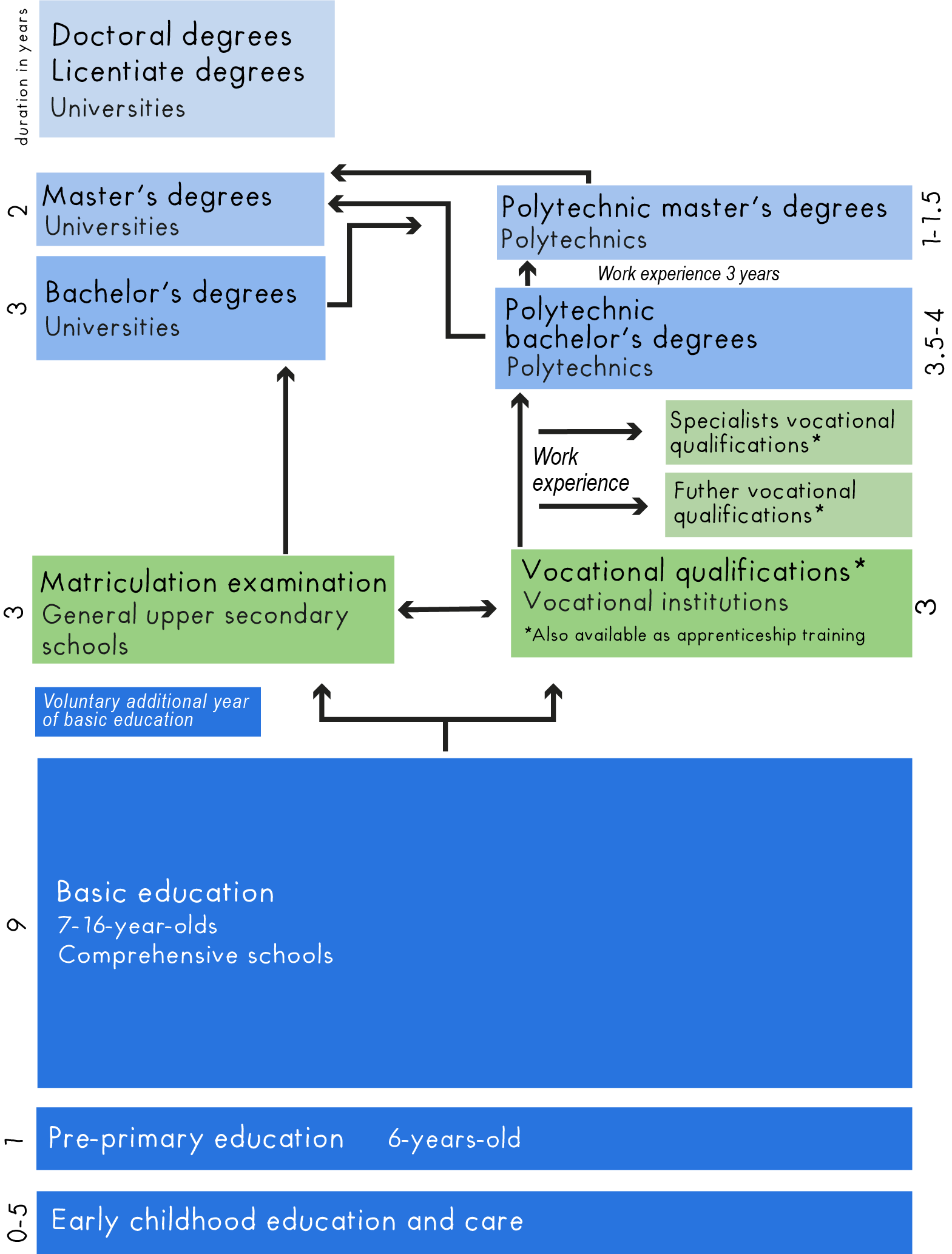

Finland also provides a No Dead-End education system, designed to provide choice and access to higher education for all students. The system also allows for avenues to change paths without lapses or interruptions in school. As indicated in (Table ), if a Finnish student chooses a general upper secondary school plan, that student may then continue to higher education, earning a bachelor’s, master’s, or doctoral degree. If they opt to pursue a vocational course at the upper secondary level, they may do so. For the student who decides on a vocational path as their upper secondary school plan, that student may also earn a bachelor’s degree from a polytechnic institute. If, at that point, the student chooses to pursue a master’s or Doctoral degree at a university, that path is also available. Hence, the term, No Dead Ends has been etched into the Finnish education system to provide choices along with the pursuit of an education.

Higher Education

Institutions of higher education in Finland, are also free of cost to its citizens. Two types of institutions are available: universities and universities of applied sciences (UAS), Both institutions offer bachelor’s and master’s degrees. Among the thirteen universities, all are public, and extensive programs and courses are offered (Higher Education in Finland, 2023). Universities “focus on scientific research and education based on it” (Fulbright Finland Foundation, n.d.). Admission is competitive and work is deemed to be rigorous. Like the compensatory education system, choice is a fundamental tenet. For example, some courses may allow students to take competency exams in place of class attendance or course requirements. An additional 23 polytechnic schools, also known as (UAS), focus on occupations in business, industry, and service. Degree programs, including professional teacher education programs, are related to the workforce and may include internships and other work experiences (JEDUKA, 2023).

Teacher Preparation

The decision to move teacher preparation programs to research universities was to elevate the profession (National Center on Education and the Economy, 2023). Standards were raised and by elevating the profession, teaching became a highly respected and revered career (Sahlberg, Vision, sustainable leadership and intelligent educational policies: The Finland story, 2007). By setting the bar high for admission to teacher education programs, less than seven out of one hundred applicants are accepted (Jehlen, 2010), and by establishing a competitive teaching job market, Finland was able to fortify its schools with exceptionally intelligent and capable educators. In doing so, trust was placed in the teachers, and they were granted the autonomy traditionally offered to well-respected professionals. Now, teacher preparation programs are highly competitive, and the profession is revered. Only one in ten applicants are accepted into teacher education programs, and all teachers are required to earn a master’s degree. Additionally, the university oversees programs “based on and supported by scientific knowledge” (Sahlberg, p. 75). Programs are consistent and entry is determined by academics, commitment to pedagogy, and a passion for education and teaching. The five-year program encourages creativity and thinking outside of the box. It prepares candidates to become autonomous yet reflective and collaborative teachers. In nations where students rank high according to PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment), teacher preparation is highly selective. Finland has one of the most competitive teacher education programs in the world (Sahlberg, Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland?, 2011). In a country where there is very little variation between schools … and where “95% of Finnish schoolchildren fulfill the OECD minimum requirements for living in a modern society,” the consistency of teacher education programs and enrollment standards is evidenced (University of Helsinki, 2006). Applicants to teacher education programs are required to “pass a rigorous matriculation examination…. possess high scores, positive personalities, excellent interpersonal skills, and (possess a) commitment to work as a teacher at a school” (Sahlberg, Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland?, 2011). Not surprisingly, teachers in Finland are respected similarly to how physicians are respected in the United States (D’Orio, 2008). High standards and a uniform educational philosophy have positively impacted longevity in the field. Finland boasts a 90% retention among its teachers; conversely, fifty percent of U.S. teachers leave the profession in the first five years (Pearson, 2005). “Those with the least training leave at more than twice the rate of those who are well-prepared” (Darling-Hammond, 2011). As Darling-Hammond and other researchers have found, the better the preparation, the greater the likelihood for the teacher to remain in the profession. In Finland, graduates of teacher education programs must pass two levels to be Sahlberghired for a teaching job. They are grouped according to their matriculation scores. This includes college examinations, “out-of-school accomplishments, and a national entrance exam in which questions focus on a wide range of educational issues” (Sahlberg, 2011).

Teacher Autonomy

Once hired, teachers devote half of their time toward “planning with colleagues, collaborating with parents, and taking part in high-level professional development” (Frysh, 2011). This lends credence to the notion of the teacher as an autonomous and capable professional. Educational reform advocates within the United States, contend that greater teacher autonomy and decision-making input will result in more informed decisions than those made by district or state supervisors; however, they acknowledge an organization that is deeply rooted in a top-down model. “Autonomy seems to be emerging as a key variable when examining educational reform initiatives, with some arguing that granting autonomy and empowering teachers is an appropriate place to begin in solving the problems of today’s school” (Pearson L. C., 2005). The teaching profession in Finland is highly respected, and the curriculum is “deeply thoughtful,” creative and cutting edge; it attracts people who lean toward “research, development and design” (National Center on Education and The Economy, 2006). Teachers are encouraged to “push their intellectual and creative bounds, and to “use their judgment” (National Center on Education and The Economy, 2006). This process places the teacher in the role of a leader and abolishes a top-down hierarchical system.

Teacher evaluations were also abolished under the new framework. The autonomy bestowed to teachers resulted in parents placing their trust and respect in the teachers. This healthy relationship establishes a strong home-school connection. Teachers are entrusted to choose what to teach, how to teach, where to teach, how and what to integrate, and how to assess. Parents are supportive of the teachers whom they view as professionals. Therefore, teachers are free to seek support services for students, take students on outdoor and overnight trips, and make choices they deem appropriate.

Autonomy and Efficacy

Teacher autonomy is also linked to efficacy and emerges as a key variable toward student achievement. Autonomy means having control over oneself and one’s work environment (Pearson L. &., 2006). Thus, a pecking order is viewed as antithetical to an autonomous work setting. Teacher autonomy is related to collegial relationships within the school setting, shared decision-making, and flexibility and choice as it relates to instructional methods. “…top-down decision making often fails precisely because it lacks the support of those whose (sic) are responsible for the implementation and success of the decision” (Pearson L. &., 2006). Herein lies the polarization of public education in the United States in contrast to education in Finland. To allow one to maintain control implies and is predicated upon the premise that one has the capabilities to do so. Hence, before one can be afforded the trust inherent within an autonomous role, one must be adequately trained, educated, and prepared for the task. It is therefore essential to ensure that teachers are highly qualified before they enter the profession.

Meet the Theorist

Vilho Hirvi (1941 – 2001) started his professional career as a Finnish baseball player. After leaving baseball, he trained as a teacher and later received his doctorate. At the time of his death, he was serving as the General Secretary for the Ministry of Education and Culture of Finland.

The Effective Teacher

Teacher autonomy has also been linked to teacher effectiveness; a quality often observed in Finnish schools. Effective teachers believe in a commitment to teach all children and believe that all students can learn. They exemplify collaborative methods within the classroom, contribute to the creation of a shared vision, and practice the art of self-analysis. A plethora of research confirms a significant link between effective teachers and student achievement (Tucker, 2011). This relationship extends to teachers who create higher-quality lessons and who exhibit a high level of self-efficacy. When individuals feel competent, they act confidently. These self-reflective ideologies then impact their behavior. Humans are more inclined to perform tasks in which they feel a level of competency, while their level of efficacy determines the amount of effort expended and the willingness to persevere in the face of adversity.

School Culture

In describing the culture of schools in Finland, despite their geographical differences, a unifying precept is evident. Characteristics that define the culture of a school can often be described in terms of how it is perceived concerning its beliefs and attitudes and how these perceptions impact the behavior of both its students and teachers (Tableman, 2004). Culture is formed by the interactions of “the attitudes and beliefs of persons both inside the school and in the external environment, the culture norms of the school, and the relationships between persons in the school” (SEDL, 1992). These deep-rooted ideologies become embedded and ensconced within the school and help to define its reputation. School culture also influences student behavior achievement. In studies of turnaround schools, it was shown that student behavior correlated with schools that exemplified a positive culture by demonstrating a commitment to “moral character – treating others well….and performance character, doing things well (Character Education Partnership).” The combination of believing and behaving ethically solidified the positive culture of these schools. In identifying the traits of positive school culture, particular patterns emerge. These settings are marked by an atmosphere that includes a “safe and caring environment,” an “intellectual climate,” a clear set of “rules and policies,” and a commitment toward “shared decision making” (Character Education Partnership).

Student Achievement

Not surprisingly, student achievement has strong links within positive classroom climates, marked by those in which the teacher integrates both emotion and the interests of students and where the teacher fosters and maintains interest levels. It is exemplified within a smooth management, student-friendly environment that is permeated by measures of fair evaluations. Rules, procedures, and expectations are clear and just. It is an environment that is culturally responsive and where communication, with individuals, families, and teams of teachers, is in evidence. Hence, the culture of the school directly impacts the achievement of the student, academically, socially, and psychologically. Studies have also supported the claim that effective teachers display high levels of self-efficacy and that these same teachers promote self-efficacy among their students (Hoy A. W., 2009). Effective teachers promote a caring classroom environment in which the beliefs and culture of the students are valued within an atmosphere that fosters a belief that all students can learn (Hoy A. W., 2009).

Final Thoughts – Learning from Others

Since 2012, the United Nations Happiness Report has listed the countries in order of happiness and for the past six years, Finland has been ranked as the happiest nation. Like their high-scoring status on the PISA exams, residents at first, questioned these rankings. In conversations with Finns, I have come to realize that happiness is not about euphoria; it is not about walking about with a broad smile or an ecstatic air. Instead, happiness is about contentment. It is about living in a society that values health and well-being and part of that well-being is the education of its citizens. Happiness, or contentment is about living in a community that exalts equity for the people. It has often been asked how the education system in the United States can attain the level of success as Finland, given our societal and economic differences and the answer remains the same. To make overarching changes, a reconfiguration of values and mindfulness about the framework of education would need to occur. Like the figure (Figure 14) of children watching a baseball game, barriers that prevent access and equitable opportunities need to be removed. Systemic change needs to include a reevaluation of the core curriculum, teacher preparation and autonomy, and authentic assessment. Finland has modeled how students can and do achieve academic and social-emotional success under a system that promotes a less-is-more curriculum, within a culture of equity, founded on the principles of believing that each person can learn, and where the individual is valued and respected. When respect for the teaching profession is respected, and when the absence of threats of evaluations frees teachers and students to think critically, create, and explore in an atmosphere of joy, encouragement, and positiveness, the seeds for lifelong learning will be nourished. Your journey may lead you down the path to cultivate change on a systemic level, or your steps may be closer in stride.

Activity

Think about your educational journey. What can you do in your future classroom to establish a positive class culture?

How can equity, teacher autonomy, and happiness become embedded in the U.S. educational system?

Predict the trajectory for the next five years, based on the 2000 to 2020 PISA scores for students in the United States.

Glossary

Basic Education: Compulsory schooling in Finland for ages 7-16, divided into primary and lower secondary levels, emphasizing equity and a holistic approach to learning.

Code of Ethics: Set of principles guiding professional conduct in education, outlining expectations for ethical behavior and decision-making among teachers and administrators.

Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC): Finland’s program for children 0-6 years old, focusing on play-based learning and holistic development before formal schooling begins.

Educare Model: Finnish approach integrating education and childcare, allowing parents flexibility in choosing care options for young children with government support.

Equity: Core principle of Finnish education ensuring all students have access to high-quality education regardless of background, with resources allocated based on need.

Everyman’s Right: Finnish law allowing public access to nature regardless of land ownership, supporting outdoor education and connection to the environment.

Higher Education: Tuition-free university and polytechnic institutions in Finland offering bachelor’s and master’s degrees, with a focus on research and practical applications.

Intensified Support: Second tier of Finland’s special education system, providing targeted interventions for students needing additional help beyond general classroom support.

National Core Curriculum: Framework guiding education in Finland, outlining learning objectives and core content while allowing for local and teacher autonomy in implementation.

No Dead Ends: Finnish educational philosophy ensuring multiple pathways to higher education and career options, allowing students to change tracks without academic penalties.

Outdoor Education: Integral part of Finnish schooling emphasizing learning outside the classroom, connecting students with nature and real-world contexts across subjects.

PISA: Programme for International Student Assessment, evaluating education systems worldwide by testing 15-year-old students’ skills and knowledge in reading, mathematics, and science.

Play-based Learning: Educational approach in Finland emphasizing child-initiated, open-ended activities to develop cognitive, social, and emotional skills, especially in early years.

Pre-Primary Education: Mandatory year of education for 6-year-olds in Finland, introducing foundational skills through play-based and interactive learning experiences.

School Culture: The shared beliefs, values, and behaviors that shape the social and learning environment within Finnish schools, emphasizing trust, respect, and collaboration.

Special Education: Inclusive approach in Finland providing immediate, in-class support for about 30% of students, focusing on early intervention without formal labeling.

Teacher Autonomy: High degree of professional freedom given to Finnish teachers to choose teaching methods, materials, and assessment strategies based on their expertise.

Teacher Efficacy: Belief in one’s ability to effectively teach and positively impact student learning, strongly emphasized in Finnish teacher preparation and professional development.

Teacher Preparation: Highly selective, research-based master’s level programs in Finland, emphasizing pedagogical skills, subject knowledge, and practical training for future educators.

Tracking: Practice of grouping students by ability or achievement, abolished in Finland to promote equity and avoid limiting future educational opportunities.

Transversal Competencies: Cross-curricular skills emphasized in Finnish education, including critical thinking, communication, global citizenship, and media literacy for future readiness.

Universities of Applied Sciences (UAS): Finnish institutions of higher education focusing on practical applications and close ties with working life, offering bachelor’s and master’s degrees.

Upper Secondary Education: Post-basic education in Finland, offering students a choice between general academic studies or vocational education and training.

Vocational Education: Career-oriented upper secondary option in Finland, providing practical skills and knowledge for specific professions while maintaining pathways to higher education.

References

Ahonen, E. (2023, April 4). Finland Education Excellence; Joy of Learning! Retrieved from Learning Scoop: https://learningscoop.fi/

Alex Spurrier, C. A. (2020). The Historical Roots and Theory of Change of Modern School Accountability. Bellwether Education Partners.

BALLOTPEDIA. (2023). K – 12 education content standards in the states. Retrieved from BALLOTPEDIA: https://ballotpedia.org/K-12_education_content_standards_in_the_states

Basic Education in Finland. (n.d.). Retrieved from Nordic Co-operation: https://www.norden.org/en/info-norden/basic-education-finland

Brainy Quote. (2023). Jean Piaget Quotes. Retrieved from Brainy Quote: https://www.brainyquote.com/quotes/jean_piaget_751098

Character Education Partnership. (n.d.). Developing and Assessing School Culture: A New Level of Accountability for Schools. Washington, DC: Character Education Partnership.

City of Helsinki. (n.d.). Family Leave. Retrieved from infoFinland.fi: https://www.infofinland.fi/en/work-and-enterprise/employees-rights-and-obligations/family-leave

Council for Creative Education. (n.d.). Introduction to Finland Education. Retrieved from CCE Council for Creative Education: https://www.ccefinland.org/

D’Orio, W. (2008, June). Finland is #1! Scholastic Administrator Magazine. Retrieved April 17, 2012, from Scholastic: http://www.scholastic.com/browse/article.jsp?id=3749880

Education. (n.d.). Retrieved from OECD Better Life Index: https://www.oecdbetterlifeindex.org/topics/education/

Education in Finland. (n.d.). Homework in Finland School. Retrieved from Education in Finland: https://in-finland.education/homework-in-finland-school/#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20an%20average%20high,about%203%20hours%20a%20day.

Education reform in Finland and the comprehensive school system. (2019, September 2). Retrieved from Centre for Public Impact: https://www.centreforpublicimpact.org/case-study/education-policy-in-finland

European Commission. (2023, June 6). Early childhood education and care. Retrieved from Eurydice: https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-education-systems/finland/early-childhood-education-and-care

European Commission. (2023, June 2). Finland. Brussels.

Finland’s Approach to Special Needs & Inclusion. (2022, June 17). Retrieved from HEI Schools: In the U.S. special education is defined as a disability that may entail physical, cognitive, linguistic, or other developmental delays (U.S. Department of Education, 2017). as compared to children in the United States

Finnish Environment Institute. (2023, September 3). Recreation in nature. Retrieved from environment. fi: https://www.ymparisto.fi/en/nature-waters-and-seas/recreational-use-nature#:~:text=Everyman’s%20rights%20are%20the%20right,rights%20does%20not%20cost%20anything.

Finnish National Agency for Education. (2023). national core curriculum for basic education. Retrieved from Finnish National Agency for Education: https://www.oph.fi/en/education-and-qualifications/national-core-curriculum-basic-education

Finnish National Agency for Education. (2023). Basic Education. Retrieved from Finnish National Agency for Education: https://www.oph.fi/en/education-system/basic-education#:~:text=Basic%20education&text=Primary%20and%20lower%20secondary%20education%20lasts%20for%209%20years%20and,It%20includes%20grades%201%2D9.

Finnish National Agency for Education. (n.d.). Higher Education. Retrieved from Studyinfo: https://opintopolku.fi/konfo/en/sivu/higher-education

Finnish student teachers’ ideas of outdoor learning. (2021). Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning, 146 – 157.

GONE71. (2020, April 26). Find Wilderness Huts and Shelters in Finland – A Detailed Guide. Retrieved from GONE71: https://www.gone71.com/shelter/

Hancock, L. (2011, September). Why Are Finland’s Schools Successful? Smithsonian Magazine. Retrieved from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/innovation/why-are-finlands-schools-successful-49859555/

Heron, C. (2019, March 4). What is a Transversal Competency? Measuring People, The 4th Industrial Revolution. Retrieved from https://vivagogy.com/2019/03/04/transversal-competencies-2/

Higher Education in Finland. (2023, March 13). Retrieved from JEDUKA: https://www.jeduka.com/articles-updates/finland/higher-education-in-finland

Hoy, A. W. (2009). Instructional Leadership: A Research-Based Guide to Learning in Schools, Third Edition. Boston: Pearson.

Hoy, W. &. (2008). Educational Administration: Theory, Research, and Practice, Eighth Edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill.

Jarvinen-Taubert, J. (2022). Education Outside Classroom – The secret ingredient of Finnish education excellence. Tampere: The Learning Scoop.

JEDUKA. (2023, March 13). Higher Education in Finland. Retrieved from JEDUKA: https://www.jeduka.com/articles-updates/finland/higher-education-in-finland

Jehlen, A. (2010). How Finland Reached the Top of the Educational Rankings. National Educational Association.

Laboratory for Student Success and the Institute for Educational Leadership. (n.d.). Creating a Learning-Centered School Culture and Climate. Washington, D.C.: e-Lead. Retrieved February 20, 2012, from http://www.e-lead.org/resources/resources.asp?ResourceID=25

Longsworth, F. P. (1966). The Making of a College. Boston: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Martin, J. L. (n.d.). Legal Implications of Response to Intervention and Special Education Identification. Retrieved from RTI Action Network: http://www.rtinetwork.org/learn/ld/legal-implications-of-response-to-intervention-and-special-education-identification

National Association of Secondary School Principals. (2023). Tracking and Ability Grouping in Middle Level and High Schools. Retrieved from NASSP: https://www.nassp.org/tracking-and-ability-grouping-in-middle-level-and-high-schools/#:~:text=The%20term%20tracking%20refers%20to,is%20appropriate%20to%20their%20needs.

National Center on Education and the Economy. (2023). Context. Retrieved from NCEE: https://ncee.org/country/finland/

National Center on Education and The Economy. (2006). Finland. Center on International Education Benchmarking.

National Initiative for School Heads’ and Teachers’ Holistic Advancement. (n.d.). What are Transversal Competencies?

New York School Bus Contractors Association. (n.d.). Retrieved from NYSBCA: ysbca.com/fastfacts#:~:text=Nationally%2C%2026%20million%20children%20in,and%20from%20school%20each%20day.

Office of Special Education and Rehabilitative Services. (2017, May 3). IDEA. Retrieved from U.S. Department of Education: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/d/300.301

Overview. (n.d.). Retrieved from IES NCES National Center for Education Statistics:

Pajares, F. (1996). Self-Efficacy Beliefs in Academic Settings. American Education Research Association, Vol. 66, No. 4, 543-578.

Pawlas, G. E. (2008). Supervision for Today’s Schools; Eighth Edition. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons.

Pearson, L. &. (2006). Continuing Validation of the Teaching Autonomy Scale. The Journal of Educational Research, 172-178.

Pearson, L. C. (2005). The Relationship between Teacher Autonomy and Stress, Work Satisfaction, Empowerment, and Professionalism. Educational Research Quarterly, 38-54.

PISA Scores By Country. (2023). Retrieved from Data Pandas: https://www.datapandas.org/ranking/pisa-scores-by-country#full-data

PISA student performance in Finland from 2000 to 2018, by subject and score. (2023). Retrieved from Statista: https://www.statista.com/statistics/986919/pisa-student-performance-by-field-and-score-finland/

S. (n.d.). Retrieved from ECECEDCN-Finland: https://www.oecd.org/education/school/ECECDCN-Finland.pdf

Sahlberg, P. (2015). Finnish Lessons 2.0 What can the world learn from educational change in Finland? New York: Teacher’s College.

Schools, H. (2022, June 17). Finland’s Approach to Special Needs & Inclusion. Helsinki: Hei Schools. Retrieved from HEI Schools: 2022

SEDL. (1992). School Context: Bridge or Barrier to Change. Austin: Southwest Educational Development Laboratory.

Tableman, B. &. (2004, December). School Climate and Learning. Best Practices Briefs – Michigan State University, pp. 1-10.

The Brookings Institution. (2013). The Resurgence of Ability Grouping and Persistence of Tracking. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution.

The Irish Journal of Education. (2023). Who takes part in PISA? Retrieved from Educational Research Centre: https://www.erc.ie/studies/pisa/who-takes-part-in-pisa/#:~:text=Which%20countries%20participate%20in%20PISA,about%2088%20in%20PISA%202022.

Top Education Degrees. (2023). What Does it Mean to “Teach to the Test”? Retrieved from Top Education Degrees: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED606415.pdf

Tucker, M. (2011). Teacher Quality: What’s Wrong with U.S. Strategy? Educational Leadership, 42.

U.S. Department of Education. (2017, May 2). Sec. 300.39 Special education. Retrieved from IDEA Individuals with Disabilities Education Act: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/regs/b/a/300.39

University of Helsinki. (2006). Department of Teacher Education. Retrieved August 1, 2012, from University of Helsinki: http://www.helsinki.fi/teachereducation/about/pisa.html

What is early childhood education and care? (2023). Retrieved from Finnish National Agency for Education: https://www.oph.fi/en/education-and-qualifications/what-early-childhood-education-and-care

Wiley University Services. (2013). Response to Intervention. Retrieved from Special Education Guide: https://www.specialeducationguide.com/pre-k-12/response-to-intervention/

Zembylas, M. &. (2004, Vol. 42). Teacher Job Satisfaction in Cyprus: The Results of a Mixed Methods Approach. Journal of Educational Administration, 357-374.